At the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, bits of rock from outer space are a chance to contemplate our place in the universe.

by Hampton Williams Hofer | photography by Joshua Steadman

As star-gazing couples huddle under their blankets this month peering up at the night sky, some may spot what they believe to be a shooting star. It could be — but more likely, that burst of light actually marks the fiery descent of space debris entering the Earth’s atmosphere.

While rocky bits from the solar system rain down on Earth every day, most of the pieces that come our way disintegrate before reaching the ground. The rocks that do land are meteorites, and you can see a vast array of them on display outside of the Astronomy & Astrophysics Research Lab (AARL) at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences.

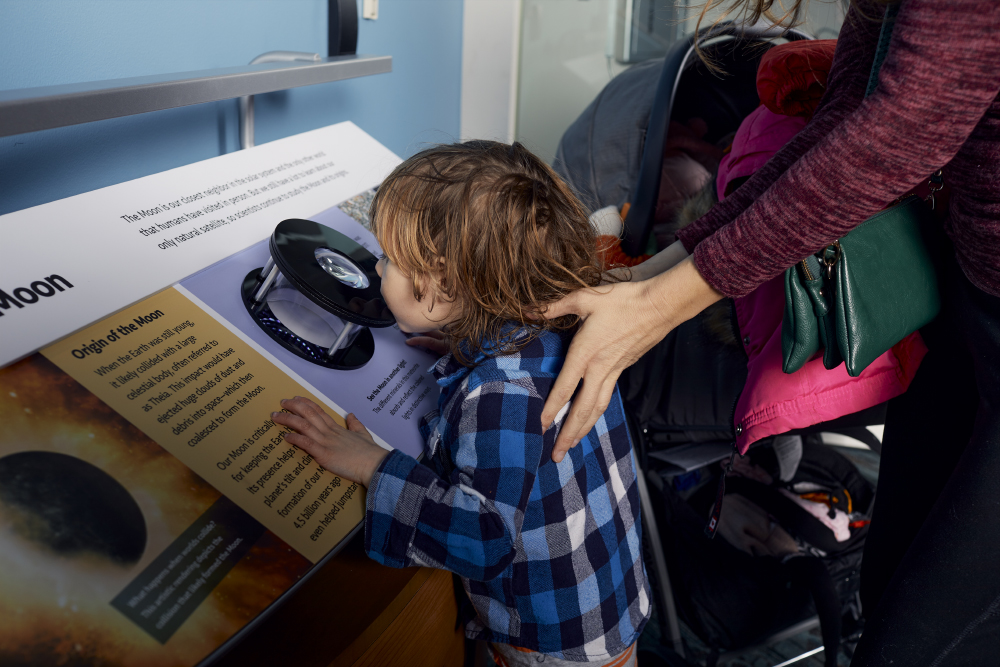

Considering that 75% of our planet is covered in water, and that many meteorites often look no different than any other rock, these objects are extremely difficult to find. Even rarer — we’re talking 0.1% of them — are lunar meteorites, rocks that were ejected from the surface of the Moon as the result of a comet or asteroid striking its surface. The NCMNS now has one such lunar meteorite of its very own. Acquired last year, and very scientifically named “NWA 11474,” this captivating little hunk of Moon sits inside a magnified display case in the recently installed “Mysteries of the Moon” exhibit, free to the public. Inside its cylindrical container, LED lights change colors to highlight the different minerals in the rock so viewers can see that it’s filled with color and texture, a mosaic of orange and black and gray — otherworldly.

Dr. Rachel Smith, head of the AARL and curator of meteorites at the museum, has been working to build its impressive collection. Last year, she reached out to a dealer in Texas about procuring a piece of a lunar meteorite that had been found in Northwest Africa in 2017. “I specifically wanted to procure a lunar sample, because we didn’t yet have a meteorite from the moon,” Smith says. “I think the Moon is fascinating — humanity has such a strong connection to it. The Moon plays a strong part in our cultural history, and we might even owe our own existence to the Moon, for keeping our planet habitable. It’s hard to imagine the night sky without it.”

Smith sought a piece of the Moon that would be interesting both to visitors, who can examine it through glass, and to scientists, who plan to do a nondestructive analysis of NWA 11474. The meteorite was purchased through an endowment, and arrived via FedEx (how terrestrial!) to its new home here in Raleigh. “People really like to have a direct connection with objects, seeing them with their own eyes rather than just through images,” Smith says. “I watch kids and adults stand for several minutes staring at the display and watching the colors shift over the rock.”

Having a piece of the Moon in downtown Raleigh is wildly cool, but it’s not our first one. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 17 mission to the moon, after which President Nixon gifted each of the 50 states a Moon rock brought home by the astronauts. That sample sits on display in the case next to NWA 11474. “To be able to see a piece of the Moon up close, knowing that astronauts physically brought it back to Earth, is incredible. We should keep in mind that this was the last time we have ever been to the Moon, and we want to go back to the lunar surface this decade,” Smith says. The Apollo 17 sample — a dark rock, basalt, obtained from the Taurus-Littrow Valley on the Moon’s surface — is from a different part of the Moon than NWA 11474, which is from an area not yet visited by humans.

NWA 11474 was found by meteorite hunters trained to search in dry, underpopulated places — like Northwest Africa or Antarctica — where the chances of finding such a sample are higher. Meteorites endure extreme surface melting and pressure on their way to Earth, and are often covered in a “fusion crust” that makes them darker than regular rocks, which is easier to spot in light terrains. A chemical analysis is typically necessary to confirm that a rock is in fact a meteorite. The collection at the NCMNS includes meteorites found all over the planet, from Mexico to France to Australia. The Moon, our natural satellite, closest neighbor, and the only other world humans have visited in person, likely aided in the formation of life on Earth billions of years ago. Its existence regulates Earth’s tilt and climate; we depend on it for habitability. Throughout history, it has been a constant subject of intrigue in art and spirituality. And now, in a glass viewing case at the NCMNS, visitors can see this ostensibly humble object that invites questions and philosophizing.

“The meteorite and Apollo sample are tangible reminders that while we have one permanent home — Earth — we can not only obtain bits of our celestial neighbors, but also travel to space,” Smith says. “We should always be thinking about how to go farther and explore the mysteries beyond our planet — but in the meantime, anyone can come here to be inches from the Moon.”

_

This article was originally published in the February 2022 issue of WALTER magazine.