A look at the history of a famous golf course and how’s it has evolved to become the home of the upcoming U.S. Open men’s tournament.

by Lee Pace

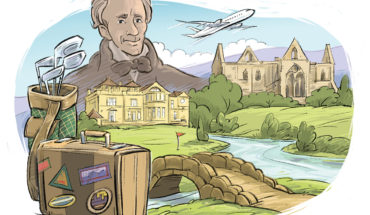

On a December day in 1935, Donald Ross hosted A.W. Tillinghast at Pinehurst No. 2.

Ross, then 63, the son of a Scottish stonemason, was an apprentice in his 20s to legendary golf pro Old Tom Morris at St. Andrews. He set up shop in Pinehurst in 1900 and designed notable golf courses across the eastern United States, from Seminole Golf Club in Florida to Inverness Club in Ohio.

Tillinghast, 59, was the son of a rubber goods magnate in Philadelphia. He fell under the spell of golf on a visit to St. Andrews in 1896, where he established a mentor-mentee relationship with Morris. Tillinghast’s golf course design acumen stretches from San Francisco Golf Club on the West Coast to Winged Foot Golf Club and Baltusrol Golf Club outside of New York City.

Tillinghast visited as a consultant with PGA of America, which in 11 months would conduct its flagship competition, the 1936 PGA Championship, on Pinehurst No. 2.

Ross showed his guest the green complexes that he had just converted, with the help of green superintendent Frank Maples, from their previous flattish sand/clay structure to undulating Bermuda grass, shaping the sandy soil around them into dips and swales. He noted the roll-offs around the greens, how they penalized shots even slightly mishit and propelled balls into the hollows nearby.

They felt the taut turf under their feet, reveling in how the drainage qualities of the sandy loam made for the ideal golf playing surface. Ross explained the choices golfers had off the tee — on the par-4 second, for example — showing his friend the lovely view into the green from the left side of the fairway, but pointing out the gnarly bunker complex a player had to flirt with to get there. Ross nodded to the native wiregrass that grew in profusion along the fairways and how it reminded him of the whins of his native Scotland.

“Without any doubt Ross regards this as his greatest achievement, which is saying a great deal,” Tillinghast said after his visit. “Every touch is Donald’s own, and I doubt if a single contour was fashioned unless he stood hard by with a critical eye. I told him with all honesty that his course was magnificent, without a single weakness.”

Pinehurst No. 2 would continue to be the site of the North & South Open on the PGA Tour through 1951, with Ben Hogan, Sam Snead, Bryon Nelson and Ross himself among the winners. It would host the 1936 PGA (won by Denny Shute) and the 1951 Ryder Cup (won by the Americans, 9.5 to 2.5, over the team from Great Britain and Ireland).

But it wasn’t in the mix to host a U.S. Open through the 1970s. That was simply impossible, because Pinehurst shut down for the summer and the American national championship was always played in June.

Even when the resort went to a year-round operating calendar, the idea was still problematic, because of the USGA’s preference for playing courses with firm and fast greens, a challenging task on Southern courses during hot weather months. The U.S. Open was not played in the muggy Southeast until venturing to Atlanta Athletic Club in 1975, though it had already visited hot spots in Houston, St. Louis, Dallas and Fort Worth.

About the time Jerry Pate was winning in Atlanta, officials at Pinehurst Country Club began floating the idea of an Open for No. 2. The Diamondhead Corporation was five years into its ownership of Pinehurst after purchasing it in 1970 from the Tufts family, whose patriarch, James W. Tufts, had launched the town and resort in 1895 as a refuge from the cold winters of New England. The Diamondhead president, Bill Maurer, conceived the World Open on the PGA Tour and the World Golf Hall of Fame in the early 1970s and wanted all the traffic, attention and accolades he could muster for Pinehurst and its No. 2 course.

It took two more decades to figure out how to bring the National Open there.

First, there were the dodgy finances of the resort and club, which eventually went bankrupt and was taken over by eight banks for two years beginning in March 1982. Robert Dedman Sr. and his Club Corporation of America bought the facility in 1984 and provided what has turned into four decades of stability, innovation and financial security, with Robert Dedman Jr. taking the baton after his father died in 2002.

Second, there was the issue of the playing surfaces.

Pinehurst and other golf courses in the Mid-Atlantic or so-called “transition zone” have forever been vexed over the choice for their putting surfaces — between Bermuda grass, the de facto choice for Florida and warm-weather climes, and bent grass, which thrives in the North. Pinehurst officials experimented with new strains of both over the 1970s and ’80s, walking a tightrope between offering smooth and playable greens for 12 months of the year and making them lightning-quick in the summer for an elite competition. (Pinehurst old-timers still remember Hale Irwin and Johnny Miller taking dead aim at flagsticks during PGA Tour competitions on No. 2

in the late summer and their approach shots stopping mere feet from the hole.)

By the early 1990s, the USGA and Pinehurst officials agreed that advances in grass technology and green foundation construction would allow them to rebuild the greens to stand up to the world’s best players on a 90-degree day in June. The USGA announced in June 1993 that it would conduct the 1999 Open at Pinehurst. The competition was a rousing success from the perspective of ticket sales, corporate support, traffic ebb and flow, housing and, certainly, the golf course itself.

“It’s the most draining course I’ve played in a long time,” said European Ryder Cup team member Lee Westwood at the time.

“People sometimes ask what’s the hardest course I’ve ever played,” said two-time U.S. Open champion Lee Janzen. “Now I know.”

The Open has been contested on No. 2 twice more and the course has played as a par-70 for each championship. Payne Stewart was 1-under in winning the Open in 1999, Phil Mickelson was even-par and Vijay Singh and Tiger Woods were 1-over. Michael Campbell won with an even-par total in 2005, with Woods at 2-over. Martin Kaymer has been low man in the three Opens, shooting 9-under in 2014, but his nearest competitors were a mile back with Ricky Fowler and Eric Compton tied for second at 2-over.

The 2024 Open at Pinehurst will be the first played on the Champion Bermuda greens installed after the 2014 Open and the second of the Coore & Crenshaw restoration era. Bill Coore, a native of Davidson County who played No. 2 often during his boyhood summers, and Ben Crenshaw, the two-time Masters champion, coordinated an extensive makeover in 2010-11 that included stripping out hundreds of acres of Bermuda rough, recontouring fairways and bunkers to Ross’ design and rebuilding the perimeters with firm hardpan sand dotted with wiregrass, pine needles and whatever natural vegetation and debris might accumulate.

“In the early days, this golf course was disheveled and brown, and the ball rolled and rolled,” Coore says. “That’s what gave it its character. Over time, that was lost. It was too green and too organized.”

“Bowling-alley fairways,” Crenshaw adds. “Straight and narrow.”

Don Padgett II was the Pinehurst president and chief operating officer from 2004-14 and the man who convinced Dedman that hiring Coore & Crenshaw and taking No. 2 back to its “golden age” from 1935 through the 1960s was the correct move. Padgett is a “golf guy,” in industry parlance, coming to the resort with a background as a PGA Tour player in the early 1970s and a longtime club professional. His father, Don Sr., was director of golf at Pinehurst from 1987-2002.

One March afternoon a decade into his retirement, Padgett is sitting in a rocking chair on the porch overlooking the 18th green of No. 2. It’s sunny and 55 degrees. “I think this is what the Tufts envisioned,” he says. “If you’re from Boston, this is balmy.”

The world of golf is coming to Pinehurst this month, and the game’s top players will find the 18 holes that so impressed Tillinghast in 1935 — and will vex them in 2024.

“The golf course today probably presents itself as the best it ever has,” Padgett says. “It’s Ross’ concept, with modern maintenance behind it. I think he’d look at this golf course and say, Wow, I wish I’d had the ability to grow grass like this. It’s not distorted, it’s enhanced. I think he would bless it.”

This article originally appeared in the June 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.