This collection of plant specimens on University of North Carolina Chapel Hill preserves our natural history and guides our planet’s future.

by Susanna Klingenberg | photography by Liz Condo

If you’ve ever enjoyed a cocktail on The Willard Rooftop Lounge, with its elegant floral mural and skyline views, you’ve sipped in the shadow of our country’s natural history. In the 1880s, this land was a rambling antebellum estate where the bar’s namesake, William Willard Ashe, spent his childhood falling in love with plants and fungi, dirt under his nails and roots in his rucksack. A mural on the wall here by Taylor White nods to this passion, depicting magnolia flowers and other local flora. The Ashe family’s federal-style estate, Elmwood, still stands nearby on Boylan Street.

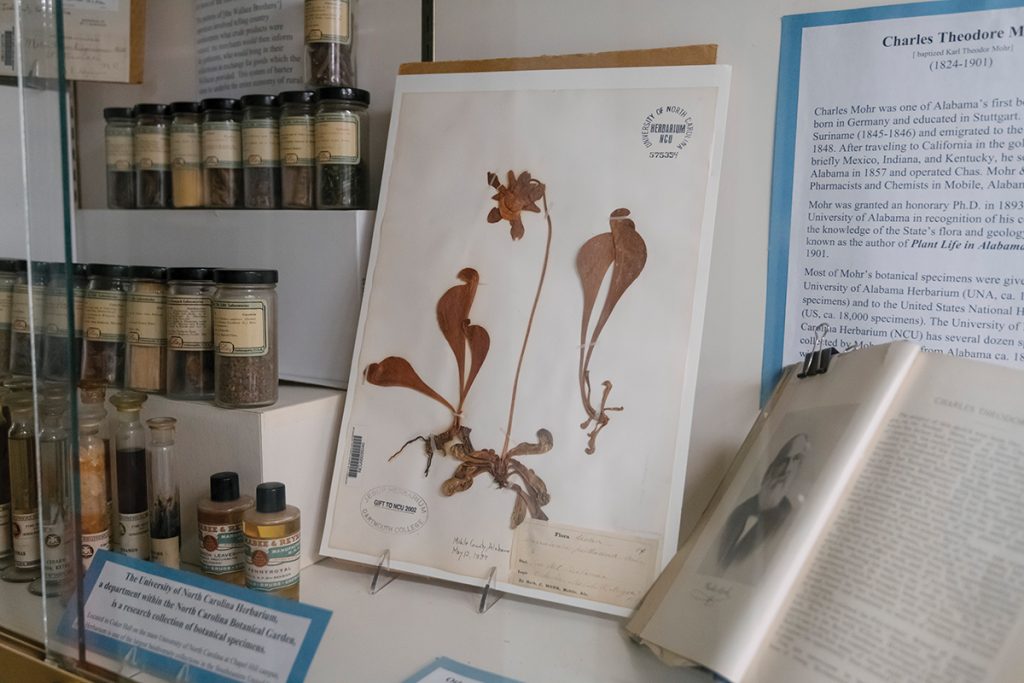

Described by one biographer as a “congenital naturalist,” Ashe collected more than 4,000 specimens from across the southeast during his lifetime — so many they required a separate house! — and made numerous contributions to the fields of botany and forestry. After Ashe was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in 1932, Dr. William Chambers Coker, then a botany professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, petitioned the university’s president to acquire Ashe’s prodigious collection. The purchase transformed the botany department’s small collection into an official university project, and the UNC Herbarium became Coker’s life work.

If you’ve never heard the word “herbarium” before, you’re not alone. “There’s a misconception that we only have parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme!” laughs Alan Weakley, the UNC Herbarium’s director. In fact, explains Damon Waitt, director of the North Carolina Botanical Garden, which oversees the herbarium, the definition is much more expansive: “An herbarium is a record of plant biodiversity over time and space.” An herbarium, then, contains samples of vascular plants, mosses, fungi, algae and lichen over all time and all space, including land and water. The practice of collecting plants, or herbaria, dates to the 1400s. “Back then, if you were a doctor or a priest, you were collecting plants for medicinal use,” says Weakley. “Even today, the majority of medicines we use are based on plant compounds.”

Ashe’s and Coker’s legacies have been joined by the work of other researchers and enthusiasts to create a collection that is worldwide in scope and contains over 800,000 specimens collected over three centuries, with more cataloged every week. (Only Harvard University’s herbarium and a handful of other herbaria are in the same league.) Some of the collection’s fossils date back to the Devonian period, around 416 million years ago — before the dinosaurs!

What brings these specimens to life are their stories. There is, of course, the story of each specimen’s scientific classification — a real cliffhanger, if you’re a botanist. But for the rest of us, there are also the deeply personal tales of where and how each specimen was collected and by whom. “The stories behind some of the specimens are wild,” says the UNC Herbarium’s curator, Carol Ann McCormick. “There’s drama, swashbuckling, catastrophe and missed connections… for a bunch of dried plant samples, it’s all incredibly human.” Thanks to McCormick’s curious nature and tireless research, the stories of these intrepid phytophiles infuse the herbarium’s collection with life, weaving each fragile clipping into our complicated human history.

Take, for example, the sensational backstory of the specimen Prionitis sternbergii, a red seaweed found in rocky tidepools. It was discovered by Tadeas Haenke, a Czech botanist in the 1790s. To say his quest for botanical discoveries was ill-fated is an understatement: he missed his departing ship but was able to catch another — which sank. He survived, swimming for his life while holding his most treasured possession: a copy of Linnaeus’s 1753 Species Plantarum. He then missed another ship and finally trekked solo across the Andes to meet back up with his crew — all in the name of science.

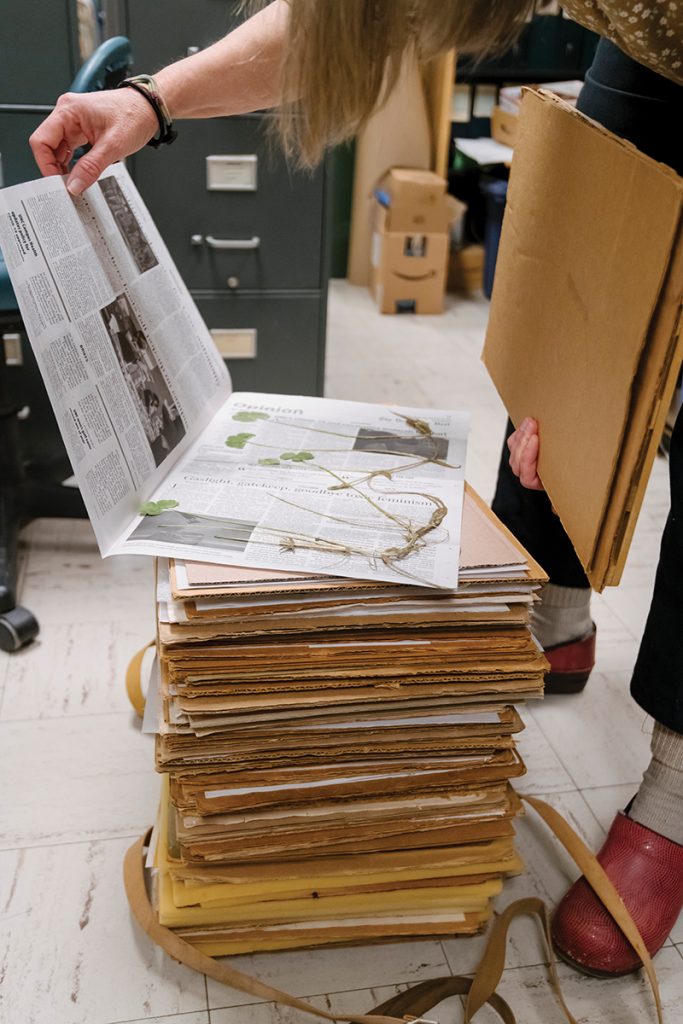

A less dramatic story is that of Becky Dill, a present-day, green-thumbed retiree who was exploring her home in Anson County when she spotted a native wildflower not typically seen in the area, the Silphium terebinthinaceum, or prairie dock. Suspecting it was a new specimen for the county, she posted a query and a picture on the iNaturalist app. When her fellow plant enthusiasts confirmed it was a new sighting, she contacted the university — which brought her number of herbarium submissions from Anson County up to 286. To McCormick, who knows the herbarium’s collectors so well she can identify their handwriting, quotidian stories like Dill’s are just as important as the epic ones, just as critical to the ongoing work of scientific discovery.

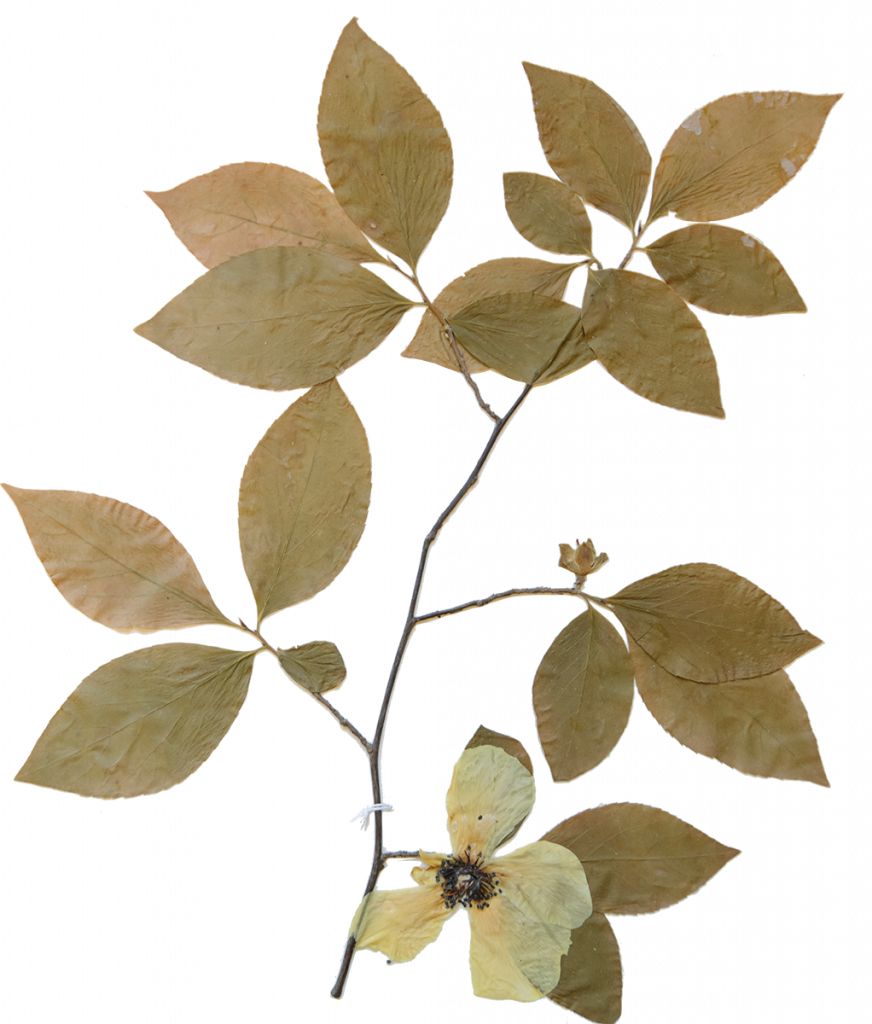

Visiting the UNC Herbarium feels like time-traveling to a medieval apothecary. It has the smell of a library and the hush of a museum. Labyrinthine rows of cabinets fill room after room and spill into the hallways, bursting with treasure from far-away places and far-off times. Flower presses preserve delicate clippings from collectors around the world, and needle and thread artfully secure them to sturdy archival paper. Yellowing labels hold beguiling Latin names — Prionitis lyallii, Clematis virginiana, Euphorbia characias — written in faded cursive that few besides McCormick can untangle.

And while some of these discoveries may be ancient, they can play a role in contemporary research. Recently, scientists discovered that they can extract and sequence DNA from the leaf samples of dried plants. One of the seaweed samples from Haenke’s unlucky 1791 adventure, for example, is the oldest specimen from which UNC plant biologists have successfully isolated DNA. “It’s kind of like 23andMe,” says McCormick. “A scientist can examine the genes in one plant’s DNA, and by comparing those genes to the same genes in other plant samples, determine how closely the plant species are related.” Findings like these may sound purely academic, but in fact they contribute knowledge to an array of fields outside botany, including food science, medicine and conservation.

Today, professional botanists are the main collectors and herbarium contributors, along with a handful of dedicated enthusiasts. Herbarium research associate Bruce Sorrie has been a collector for years, and he still gets a thrill at finding a plant that hasn’t yet been recorded. “When I spot one of those rare things, I say, Hot dog! or some other expletive,” he laughs. “Then I ask myself, Are there enough here that I can take one?” If so, Sorrie pulls one up by the roots, keeps it moist until he gets home, then puts it in a simple press to dry. When he delivers it to the herbarium, it will be examined, compared to similar species, and — with any luck — declared a unique specimen and filed away for future researchers.

While the UNC Herbarium has deep roots on Chapel Hill’s campus, it’s working on raising the funds to create room to grow. Plans are in the works for a new UNC Plant Biodiversity Research Center at the NC Botanical Garden that could house up to 3 million specimens, providing a home for an increasing number of orphaned collections across the country.

To minimize the building’s energy footprint and maximize storage conditions, specimens would be filed in a 50-degree Fahrenheit vault accessible only by a robot (similar to the Book Bot at North Carolina State University’s Hunt Library). What the herbarium might lose in apothecary charm, it would gain in scientific impact. “It could create a mecca for botanical research in the southeast United States,” says Waitt, the botanical garden director.

As our planet changes and research pushes new boundaries, the herbarium holds true to its original purpose: helping scientists tell the story of our natural world, as it was, as it is and as it will be in the future.

The article originally appeared in the December 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.