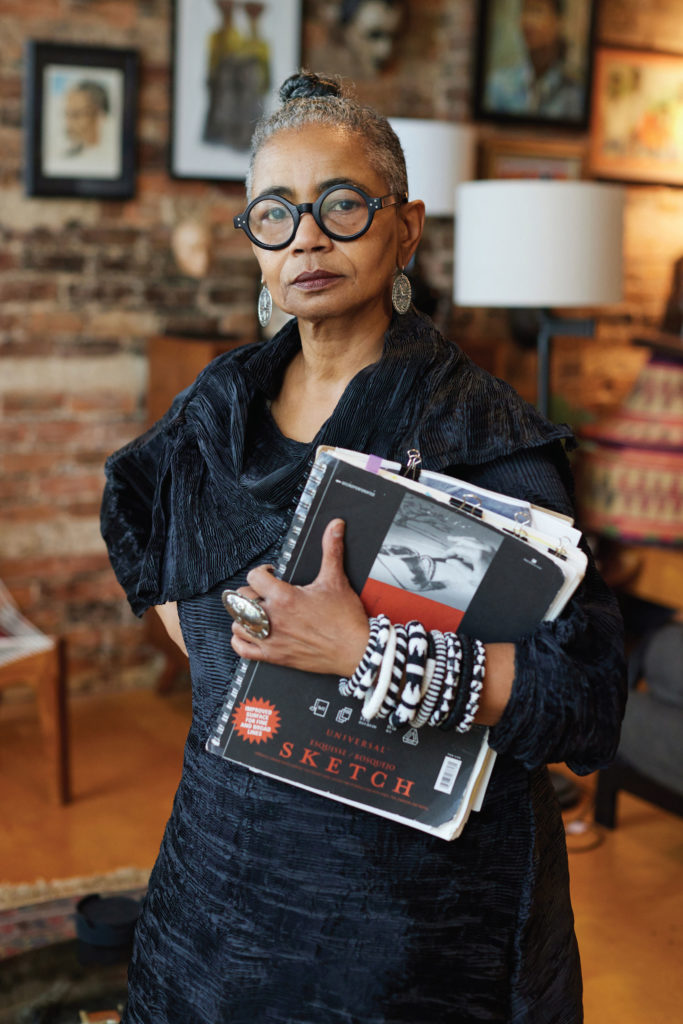

The inaugural Brightwork Fellow at Anchorlight in Raleigh, this artist reframes fabric, sewing and history through her provocative pieces.

by Colony Little | photography by Samantha Everette

“Clothing is one of our most intimate relationships,” says Precious Lovell. “Every day, we get up and we put on something to present ourselves to the world.” Whether it’s a little black dress or a well-worn baseball cap, Lovell believes clothing speaks volumes about who we are and how we want to be perceived — and that it can be a powerful tool for storytelling through art.

Fashion and art are close bedfellows for Lovell. She spent 20 years in the fashion industry, then another two decades teaching fashion, fiber and surface design. Now in her 60s, she’s a full-time visual artist, using her knowledge and expertise in textile and clothing design to create thought-provoking sculptures and installations.

As a child in Pilot Mountain, clothing — and its fabrication — was an ever-present influence on her. “I come from a family of women who stitched, whether it was quilts or clothing,” she says. “My great-grandmother lived next door to us and my great-aunt lived with us. I always had these women stitching and I was doing it myself from a very young age.”

Lovell studied fashion design at Virginia Commonwealth University and later relocated to New York City for a career in the garment industry, specializing in children’s clothing design for Healthtex and OshKosh. As a pattern maker, designer and fashion forecaster, Lovell traveled extensively, visiting 45 countries. “Travel has taught me that I’ve had to rethink my certitudes,” says Lovell. “No matter where I go on earth there’s one thing I see: Everybody is trying to strive for a better life and especially a better life for their children.”

Her travels prepared her for a new career and life abroad. She moved to Qatar in 2001 to teach fashion design at VCUarts Qatar, a school established between the VCU School of the Arts and the Qatar Foundation, a nonprofit that fosters university-level scholastic study in Doha, particularly for young women. After six and a half years teaching, she decided to pursue more schooling in fibers and surface design to augment her teaching experience. Lovell returned to the United States and earned her masters in Art and Design at North Carolina State University and continued to teach at the Oregon College of Art and Craft, Keimyung University in South Korea and North Carolina State University.

But even as she taught, Lovell pursued her own projects in visual art, using clothing and textiles as tools of communication and storytelling. Her works begin with clothing designs that are often embellished with text and symbolic imagery that convey messages of hope, history, memory, resistance and resilience. In one powerful piece, called Time’s Effing Up!, Lovell recreates the teal suit that Anita Hill wore during Clarence Thomas’ confirmation hearings for the U.S. Supreme Court in 1991. The suit contains embroidered text and black mourning ribbons with phrases that draw parallels between that era, the #MeToo movement and the 2018 testimonies of Christine Blasey Ford against Brett Kavanaugh during his own confirmation hearings. On the front of the suit Lovell places a large, red “A,” the scarlet letter that calls to task discrimination, humiliation and violence towards women nearly 200 years ago. The suit connects the past to the present, demanding that the viewer acknowledge patterns that keep repeating themselves.

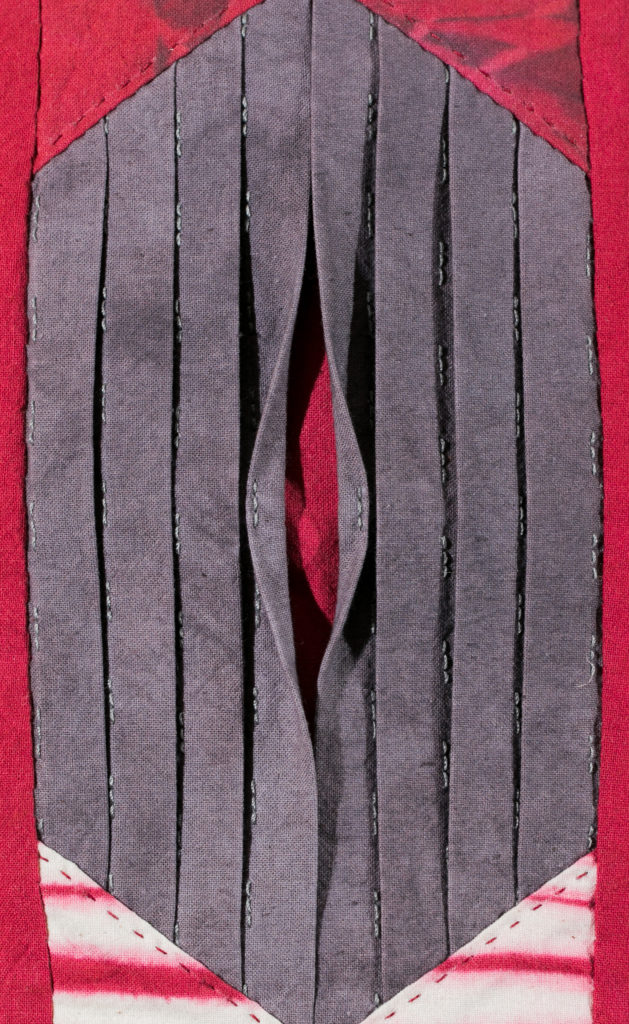

“I’m always exploring the narrative potential of cloth and clothing,” says Lovell. During an artist talk for her 2017 solo show, The Ties That Bind, at CAM Raleigh, Lovell recalled two pieces of historical needlepoint that informed her point of view as an artist: a cross-stitch by a young enslaved African-American girl with a call for the end of enslavement, and an embroidered piece by an English girl who’d left home at 13 to become a nursery maid. “She stitched about things that had happened to her that were ‘so horrible she could not speak of them,’” says Lovell. In the absence of other platforms, she says, “cloth was likely the only safe place and stitching was likely the only safe means they had to express these powerful things.”

For Lovell, these examples reframe sewing and needlepoint, so often dismissed as “women’s work,” as an important tool for preserving memory and asserting voice. “It’s always been viewed as this sweet, quiet, nonconfrontational thing that women do,” says Lovell. “I think it can scream really important things with a stitch or a technique that evolved out of this domestic realm that women existed in.”

One of her most poignant pieces grew out of a creative collaboration with Mike Williams from the Black on Black Project, called The Legacy of the N-Word: N-slaved, N-carcerated, N-sanity, N-destructible! Lovell designed a pair of garments worn in a performance piece that was part of a group show called Black on Black V2 at VAE Gallery in 2017. In one piece, Lovell fashioned a straitjacket with bolls of cotton tumbling out from the back; the year 1619, when the first enslaved African people were brought to the United States, is stenciled on the front. Its partner piece is a long black hoodie stenciled with the year 2019 and a Kongo cosmogram, a traditional cultural symbol, on the back.

While the piece is a commentary on the 400 years of brutality African Americans have endured, it’s also a powerful allegory on resilience. During the performance piece, models wearing the garments faced each other, with cotton bolls and bullet casings on the floor around them.“It’s about how the past is influencing the present,” says Lovell, noting one frequently misinterpreted element of the piece. “The symbol on the back of the hoodie looks like a shooting target, but it actually represents birth, life, death and rebirth — that’s why it’s called N-destructible.”

In October 2021, Lovell was named the inaugural artist-in-residence for Anchorlight’s Brightwork Fellowship. “Artists need time, space and money,” says Anchorlight creative director Shelley Smith, who co-founded the studio with James A. Goodnight. Smith notes that the purpose of the fellowship is to make North Carolina artists know that they are “valued and validated in their practice, that they do not need to leave the state they call home for the sake of opportunity, and that opportunities of this nature will one day cease to be few and far between.”

”Lovell’s ability to balance storytelling with her technical expertise made the artist a natural choice for the Anchorlight Fellowship. Her depth of research, quality of craftsmanship, and attention to every detail of her practice is beyond reproach,” says Smith. “Her commitment to shining an unflinching light on American history while also creating objects of careful beauty and consideration results in work that holds powerful space, speaking to both our past and present, asking us not to look away.”

Research fuels Lovell’s ideas. On her desk sits a pile of art and textile books that support the themes in the solo exhibition she’ll present at the end of her fellowship. The wall of her studio space is dedicated to reference images, quotations, sketches and materials that map out the ideas for the show, while the rest of the studio space contains dress forms, found objects and material — all the trappings of her work in process.

While previous solo exhibitions showcased distinct design practices that she aligned with specific narratives, Lovell’s work for her Anchorlight show will include a broad range of techniques including quilting, embroidery, crochet and clothing design, which will each contain both coded and overt messages about inequality and the legacy of slavery. While she won’t divulge the themes ahead of time, Lovell promises to pull no punches, putting on a show that will require slow and purposeful looking, while also creating a safe space for healing and growth.

Anchorlight’s selection of Lovell also affirms how important it is to support artists at all stages of their career, no matter when they choose to embark on their journey. “I’m Black, I’m female and I’m over 60 — those are not things that are often celebrated in America’s art world or the art world in general,” she says. “I feel like this is a great opportunity for me. I’m a North Carolinian, I’m a native daughter. I feel like if I can’t talk about N.C., who can?”

This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of WALTER magazine.