At the North Carolina Museum of Art’s annual celebration in florals, guests and participants alike see the collection in a new way.

by Hampton Williams Hoffer | photography by Workshop Media

This month, the West Building at the North Carolina Museum of Art will come alive in a whirlwind of color bursts and whimsical structures — and notes of rose, hydrangea, and calla lily.

It’s been more than two years since the last Art in Bloom event — the annual celebration in which floral designers display their interpretations of works within the museum — and Raleigh is ready. For months, more than 30 floral designers have been planning, testing, and prepping, working on their creations. This year, Art in Bloom, which typically draws thousands of guests, will be offered both in-person and virtually.

The floral designers who participate are a mix of professional florists and talented amateurs. But there is nothing virtual about the work that goes into their creations.

Here’s how it works: designers apply by sending in photos of their floral work, and, once selected, are assigned a piece from the museum’s collection by lottery. In a fun twist, designers are allowed to trade assignments until everyone is happy, just as long as it’s all nailed down before they leave the museum. Some trade because they’ve already worked with similar art, or they prefer 2D to 3D, or just because another piece strikes them.

“Most times this works out,” says AIB coordinator Laura Finan, “but some years, folks are a little less than excited about their piece. Interestingly, those designers who don’t like their selection often learn to love and appreciate it once they dig in.” The lottery happens in February, so the AIB designers have about four months to work on their floral responses to oil paintings, sculptures, and still lifes.

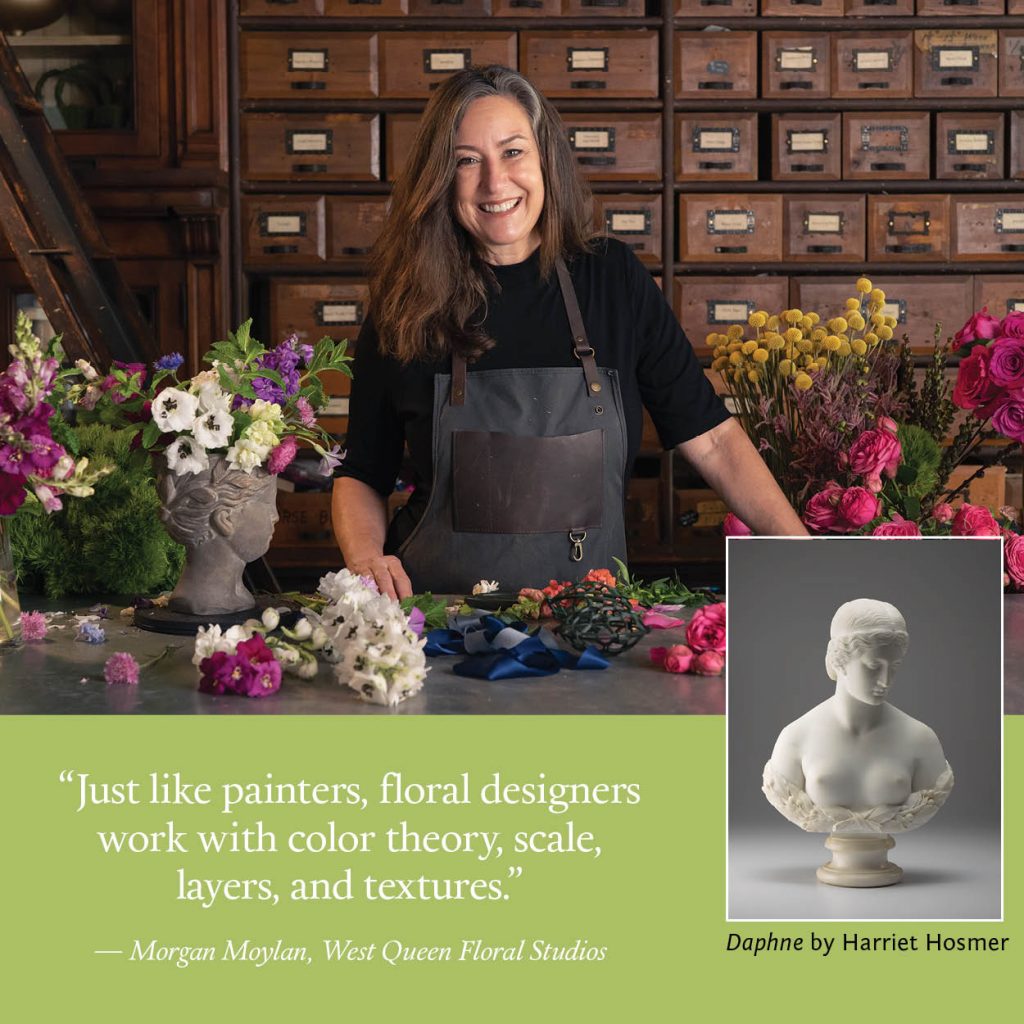

This year, Morgan Moylan, of Hillsborough, has been assigned the bust Daphne, carved from marble by Harriet Hosmer in 1853. The story behind the sculpture inspired Moylan’s vision: In Greek mythology, Daphne was a nymph who narrowly escaped the unwanted advances of Apollo by transforming into a laurel tree. “Her beauty makes her the target of the warrior god, and in order to save herself, she must give up her beauty and become a shell of who she was,” Moylan says. “I had no desire to try to replicate the fabulous work, so instead, I imagined Daphne as she sank into the laurel tree: What would that look like? How can I continue the story the artist began?”

For Moylan’s floral continuation, she will shape green chicken wire into a ghost bust of Daphne rising from a bed of laurel, with flowers like allium, garden roses, and craspedia. In a nod to Hosmer’s use of marble, Moylan will employ bleached ferns to outline the form. Behind the bust, birds of paradise indicate the natural world’s color and identity — and the absence of Daphne’s. The process is a chance for Moylan to shift from a florist to an artist. “Art in Bloom has actually helped me rethink how I describe myself and what I do,” she says. “Just like painters, floral designers work with color theory, scale, layers, and textures.”

In order to protect the art in the museum, AIB participants may only use plants pre-treated for pests, and they may not use materials that would cause damage to the art or the public: no glitter, shedding materials, loose materials, or jagged edges. The majority of each installation must be fresh plant material, not dried. Even with these stipulations, it’s a welcome chance for the florists to flex their creativity. “In the world of events, the arrangements are often dictated by our clients — but this allows us to experiment with colors, blooms, and techniques,” says Moylan. “I spend much more time noodling over what to create than creating itself.”

The museum is particularly thrilled to host this fan-favorite event after its pandemic-forced cancellation last year. Art in Bloom attracts guests of all ages, cameras ready; it’s a way to reach new visitors with a looser, buzzier format than the typical gallery visit. Many of the designers like to listen to the conversations around the floral arrangements: children fascinated by colors and shapes, gardeners arguing over bloom varieties, spouses who act like they’ve been dragged along — and then find themselves awestruck.

“It is such a great way to make art accessible to even more people, to make it exciting,” says NCMA director Valerie Hillings. “The flowers, combined with our collection, inspire people to look carefully and be reactive in how they think about what they are seeing.” Hillings delights in the cross-cultural and cross-generational success of Art in Bloom, and in the meticulous work that the florists put in behind the scenes. “They come each day before opening, and it’s a fun time to see how they keep their displays consistent with their visions, how they carefully water, replace blooms, and refresh their creations,” she says.

While the florists practice their creations at home, they must form their arrangements on-site, then check in daily to keep them alive and presentable for four days. The breadth and intensity of the project forms a unity that is uncommon in their field.

“With AIB, the museum has given floral designers the gift of community,” Moylan says. “Many of us have small businesses with one or two designers, and it is rare that as business people we have a chance to connect and admire each other’s work in a noncompetitive, purely creative environment.”

Charlotte designer Olivia Chisholm, a newcomer to Art in Bloom, will be interpreting Simone Leigh’s illustrious sculpture Corrugated. Chisholm started her work in florals just a year ago. She was working in healthcare in the midst of a global pandemic, stressed and weary, when the death of Breonna Taylor inspired her to lead an initiative called “Giving Black Women Their Flowers,” where she spent the summer delivering bouquets to Black women around Charlotte. It is fitting that she now interprets Leigh’s powerful sculpture, which honors the beauty and complexity of Black women.

Chisholm will use her floral artistry to mimic Leigh’s use of multi-African contexts, using traditional African florals, modern American florals Chisholm finds in the homes of Black families, and contemporary color schemes. “AIB is giving me a pedestal in a literal sense,” Chisholm says, “It means being given the space as a Black, female, floral interior artist to interpret an experience from my lens and mine alone.” Chisholm will use her floral artistry to mimic Leigh’s use of multi-African contexts, using traditional African florals, modern American florals Chisholm finds in the homes of Black families, and contemporary color schemes. “AIB is giving me a pedestal in a literal sense,” Chisholm says, “It means being given the space as a Black, female, floral interior artist to interpret an experience from my lens and mine alone.”

Asheville’s Sally Robinson, who helped organize North Carolina’s first AIB at the Black Mountain Center for The Arts fourteen years ago, has attended numerous Art in Bloom events (in various forms) from Philadelphia to San Francisco. “They draw art connoisseurs, flower enthusiasts, and lovers of drama and beauty to museums, offering unparalleled experiences,” she says. Her floral interpretation this year will focus on Juan Bautista Romero’s oil painting Still Life with Strawberries and Chocolate (circa 1775–1790). Robinson, who lived in Japan with her family for seven years, specializes in Ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging. The root of Ikebana is preservation of life, controlling shapes of vases to prolong the life of the flowers, the vase acting as more than a vessel, surface water exposed, and emphasis on the earth from which the flowers grow. Robinson’s creation for AIB will include curly willow, hydrangea, gypsophila, chestnut tree balls, and calla lily.

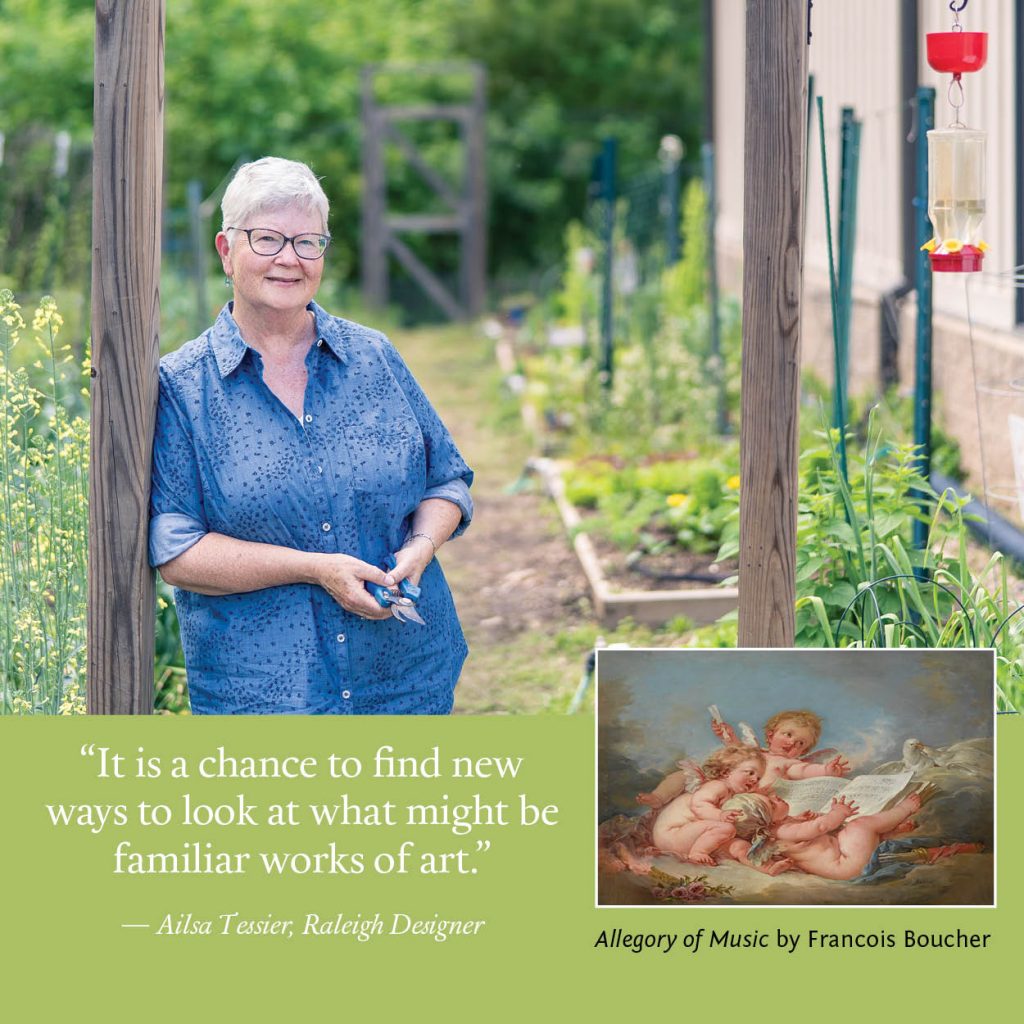

“It is a chance to find new ways to look at what might be familiar works of art,” says Raleigh designer Ailsa Tessier, who will be interpreting François Boucher’s 1752 painting Allegory of Music. The painting depicts three plump cherubs floating among the clouds with sheet music. In her unique interpretation of the Rococo work of art, Tessier hopes to flip the perception of this classic by taking the view that those cherubs are not very happy at all. Tessier also uses her art to support another cause: she’s creating her piece as a representative of The Flower Shuttle, a nonprofit that takes flowers used for weddings and events and distributes them to people living with terminal illness, poverty, and disability. “They do incredible work, and I’m so proud to represent them,”

she says.

Carol Dowd, from Southern Pines, has had a piece in AIB each year since the event debuted at NCMA in 2015, winning the Director’s Choice in 2019. This June, she will interpret Italian artist Andrea del Sarto’s 1528 oil painting Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist. “After researching the artist, I discovered he was a great colorist,” says Dowd, whose flowers will mirror del Sarto’s bold pallet. “I am planning to use a gold base and create a veil out of sticks, using pink flowers to represent the Madonna, white to represent the child, and oranges to represent John the Baptist.”

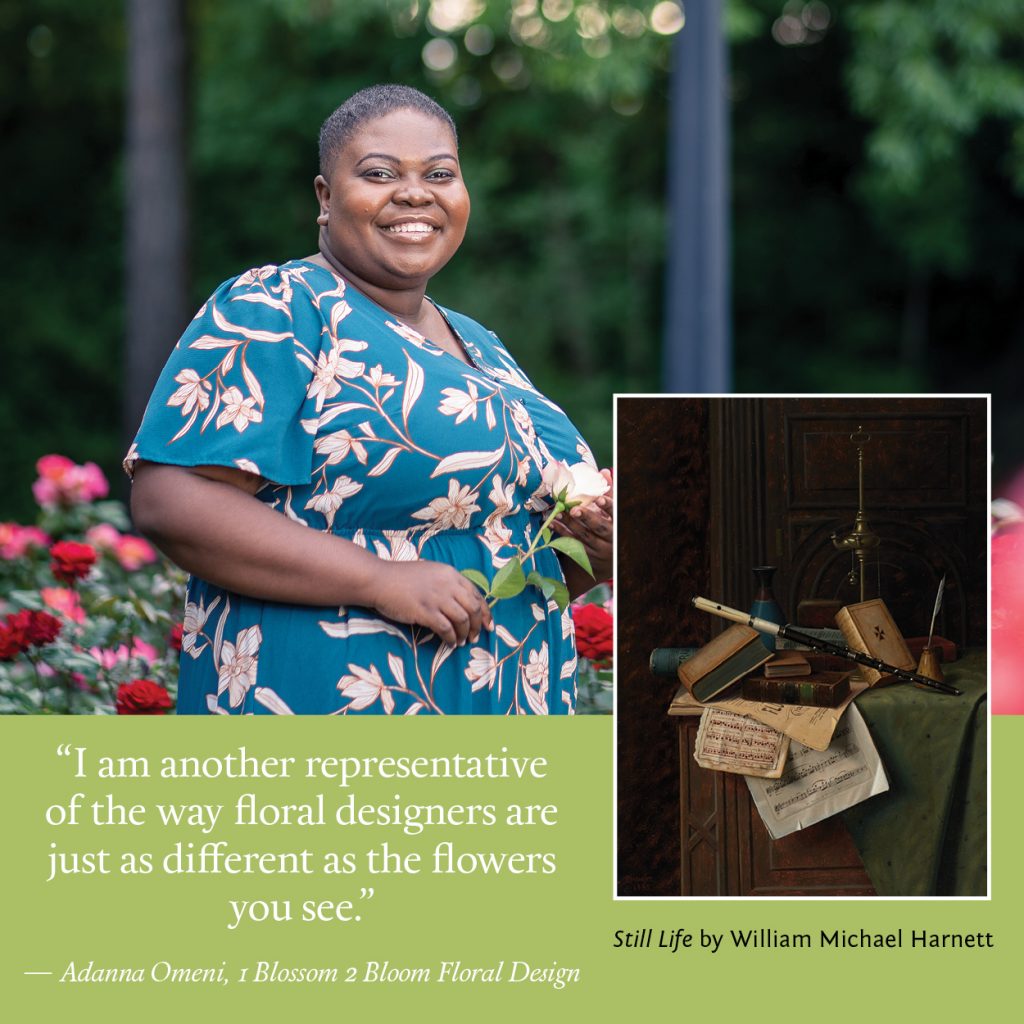

William Michael Harnett’s 1885 oil painting-on-wood panel entitled Still Life appears simple enough: a stack of books and sheet music in muted tones sit with a flute positioned on top. But when Adanna Omeni, owner of 1 Blossom 2 Bloom Floral Design in Knightdale, went to look at the piece in person, she saw it differently: “I understood that Still Life symbolizes the painter’s love for wanderlust, for getting lost in his work,” she says. “It’s an artist getting lost in love.” Omeni — in capturing the feeling of her assigned work, rather than doing a literal interpretation — will use hues of cool greens and deep blues.

Omeni derives inspiration from the work of people of color in the floral sphere: women freed from slavery who grew and curated flower arrangements to make a living, the customary flower arches that stood in meadows when Black people could not get married in churches. “I am another representative of the way floral designers are just as different as the flowers you see,” she says. For Omeni, it’s about community: she offers floral design workshops, and artistic activities like bloom bars and crown parties, to engage people who may only encounter professional flower arrangements at weddings and funerals.

Art in Bloom is a delight for the senses and the intellect, a way to revisit pieces we have seen before and perceive them through another’s eyes. And for the floral designers, there’s the added bonus of being charged to think of their own work in a new way. “I think Art in Bloom is so popular because people love the floral creations, the marriage of art and flowers,” says Dowd. “It is a wonder in a beautiful way.”

Tune in to WALTER’s exclusive video event to see more of these florists, their studios, learn how they come up with their designs, and follow along during the installation. Click here to learn more.

Pingback: 20+ Things to Do in June In and around Raleigh - WALTER Magazine