The painter follows her intuition by creating multilayered works that turn into bright, abstracted images of homes, landscapes and figures

by Colony Little | photography by Joshua Steadman

When it comes to painting, Michele Yellin believes that the messier, the better. She festoons her canvases with drips and brush splatters of acrylic paint, a form of expression that can become the finished work for some creators. But for Yellin, the mess is just the beginning. “I use it as underpainting,” she says. “It gives me some ideas of where to go.”

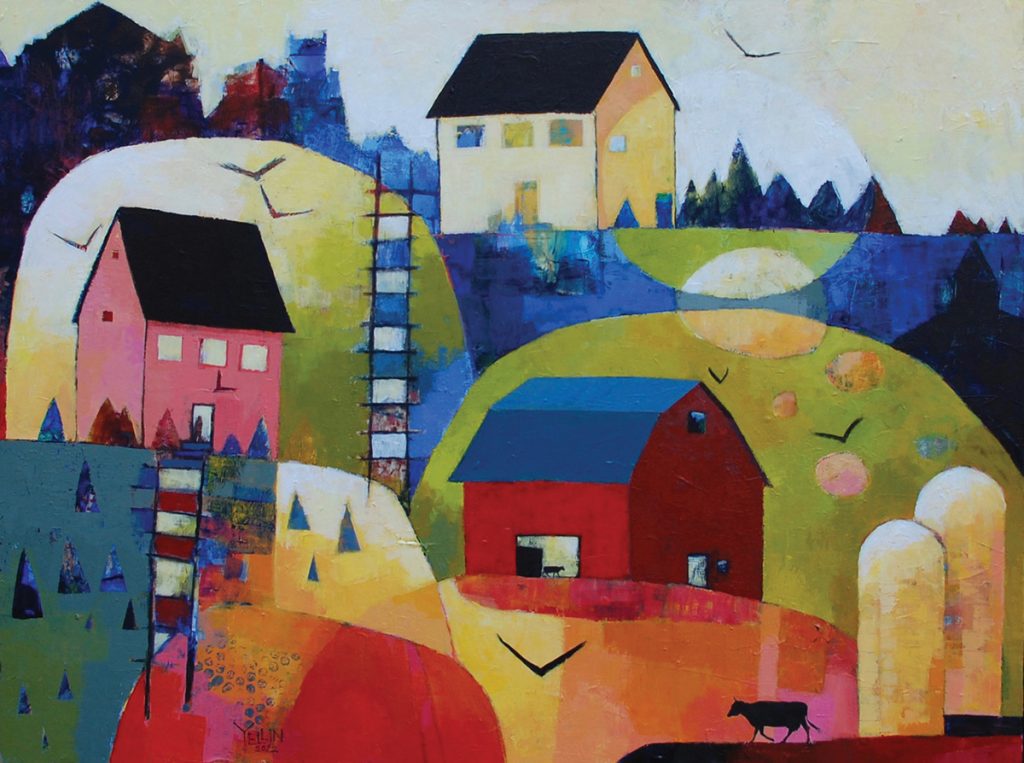

Yellin creates representational works that are inspired by these abstract underpaintings. It’s a process the artist has honed during the last 20 years, with final pieces that often depict landscapes and encounters with nature. The subjects of her paintings range from forest animals to loosely rendered homes surrounded by colorful patches of geometric shapes that form hillsides or cliffs.

Yellin has called the Triangle home since the mid-1980s. She obtained her BFA in studio art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and later moved to Cary, where she raised her family. She developed her painting practice first through using watercolor and ink on paper in her home studio.

For a long time, Yellin exhibited work in group shows and sold her work through the Hillsborough Gallery of Arts, making art while she could during two decades of raising children, caring for ailing parents and tending to a divorce. The years of caregiving left her craving additional inspiration to expand her practice, so in 2018 she started working in a studio at Artspace. “I needed an environment where I could connect with other artists,” she says. “As far as inspiration goes, looking at other artists’ work is at the top of my list. How did they do that? What are they doing there? Why does that look so great?” She also shares a home studio in Chapel Hill with her friend and roommate, the artist Jane Filer.

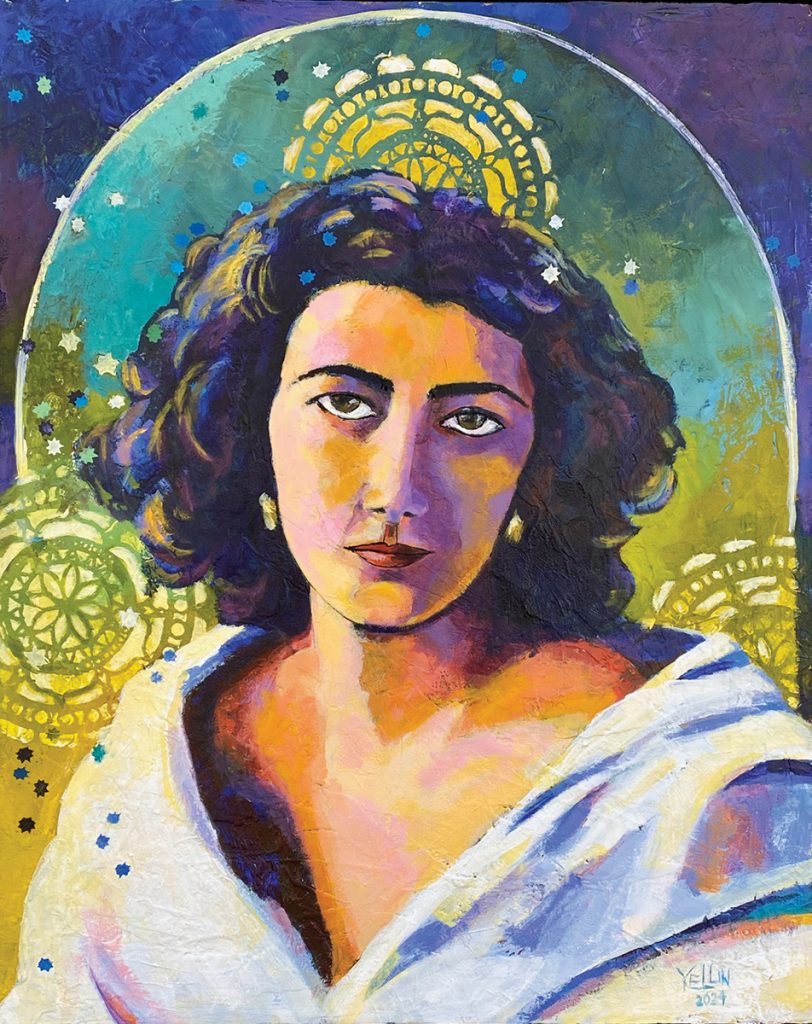

Within Yellin’s own work, layers of color, texture and shape form the foundation of each painting. Her process begins with priming the canvas, covering it with a coat of acrylic gel. From there, she begins to build color onto the canvas in bold swaths, using a variety of tools including standard paint brushes, paint rollers and printmaking brayers. Often, the underlayers include handwritten prose. She’ll also use less conventional tools — like stencils or bubble wrap — to leave subtle marks that create depth and texture. “The underpainting adds more interest and activates the surface,” she says. “It gives me some ideas of where to go.”

Usually Yellin will create five or six layers of this underpainting before she begins the figurative elements of the work. She uses vine charcoal sticks or white chalk to begin to tease out shapes, transforming the canvas from an abstract expression into a representational painting. This is where some of her most difficult work, the slow looking, takes place. “I don’t plan it,” she says. “I’ll paint the underpainting, then just sit here and stare at it.”

Yellin likens her process to gazing at clouds in the sky and watching forms emerge. “If I stare at it and nothing comes up, I’ll add more to the underpainting until it starts developing into something,” she says. Once a vision emerges, Yellin will begin to fill out her outlines using a paint shaper, an object with a wedge-shaped silicone tip that resembles a paintbrush. “It’s one of my favorite tools,” she says. Using the shaper, Yellin creates the sharp edges and lines that form strong blocks of color on her canvas.

In her studio, one work in process is a commission for Habitat for Humanity featuring five homes perched on top of a series of rolling hills. While creating the underpainting, Yellin had inscribed her thoughts on the concept of “home.” As she created the piece, fleshing out a blue sky, green hills and trees within an inviting palette of cozy fall colors, she noticed that elements of the underpainting resembled a colorful patchwork pattern. She left that portion of the underpainting intact, a nod to the organization’s practice of gifting quilts to new homeowners. “When I paint a piece, I want to make something beautiful that makes me happy and hopefully resonates with others,” she says.

Homes are a repeated motif in Yellin’s work. “When I was a kid, my dad worked for IBM, and we moved quite a bit,” she says. Until she was 6 years old, her family lived in an 1820s farmhouse in Hudson Valley, an area in rural New York, and she still has vivid memories of the home. “It was in the woods, with a pond and a dirt road,” she says. “We had a little attic that was painted yellow and there was a window; it felt magical. The house felt warm and safe.” Many of her works feature homes inspired by these memories: two-story houses with pitched roofs and a glow from the windows. In many paintings, a figure waits at the front door, as if they are anticipating the arrival of a visitor.

At any given time Yellin will have multiple canvases in her studio in various states of completion; this gives her some flexibility as she attempts to find order within the chaos of the underpaintings. She credits this intuitive approach to painting to Filer, who taught at the Carrboro Art Center for over 20 years.

Yellin recalls taking a class with her during a time when she was under a lot of personal stress. “I was in one of her workshops when Jane told me, just make a mess on your canvas, look at it and see if you can see something in it — don’t try to solve the whole thing at once,” she says.

Yellin now shares that piece of advice — to not try to figure it all out at once — with anyone who feels stuck or overwhelmed in their work, including the students she teaches at summer camp at Artspace. “I think that applies to life, too: You may know where you want to go, but you don’t know what it’s going to look like. So just take the next step,” she says. “In the middle of every painting — when it’s a disaster and I think I don’t know how to paint — I just keep going. And when it’s complete, I wonder, How did this happen?”

“Michele has a strong creative light guiding her,” says Filer. “She leads with her heart. Sharing a home and studio with her perpetuates an artistic synergy which is an experience both happily shared and extremely contagious.”And how does she know when a piece is finally complete?

Again, Yellin credits Filer for more words of wisdom. “A phrase that I learned from Jane is, you’ve got to love every square inch,” says Yellin. “I’ll put a painting on an easel and ask, Do I love every little bit of it? If the answer is yes, then it’s done.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2025 issue of WALTER magazine.