This exhibit from the North Carolina artist explores family life with themes inspired by the lockdown and murder of George Floyd.

as told to Addie Ladner

“He showed me these paintings, and I thought, wow these are incredible,” says CAM director Eric Gaard. The 16 pieces in the exhibit, titled “Unseen,” were inspired by a thought Heyward couldn’t shake after the murder of George Floyd: What would happen to my family if I was killed?

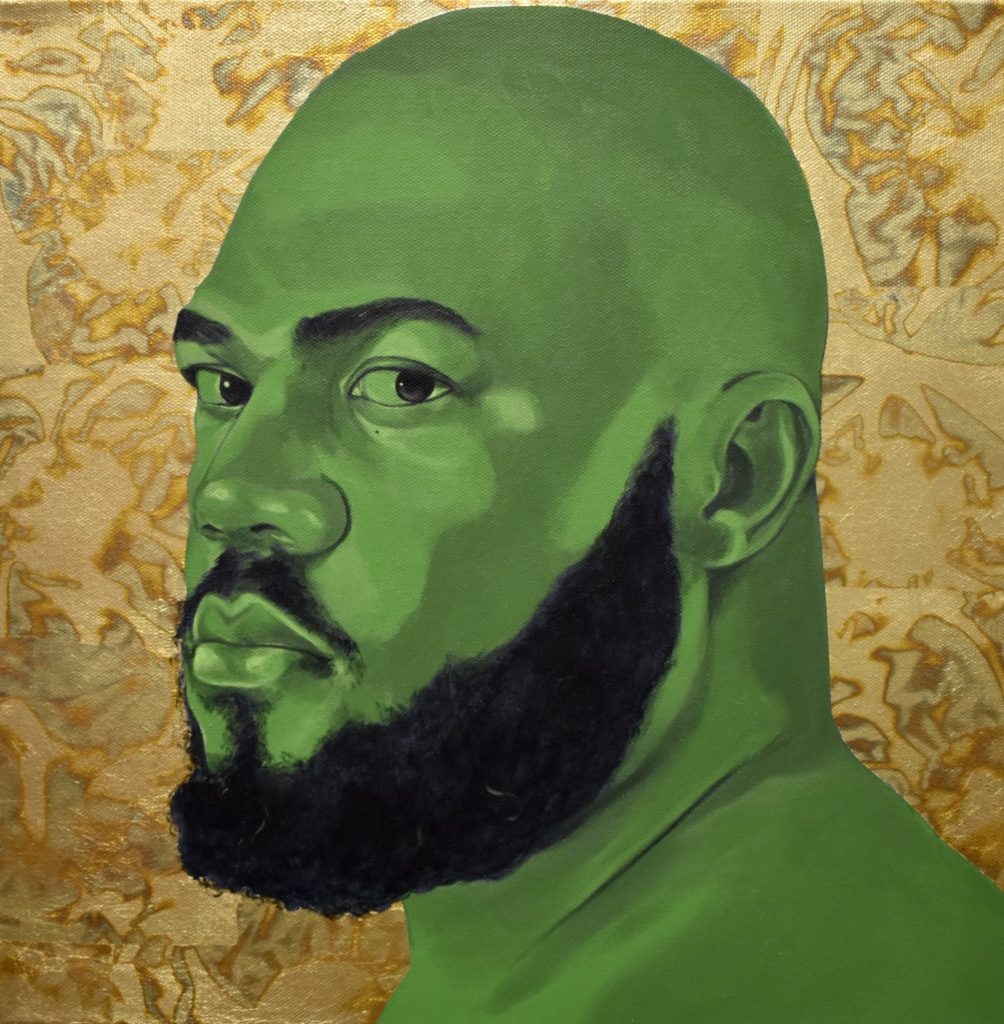

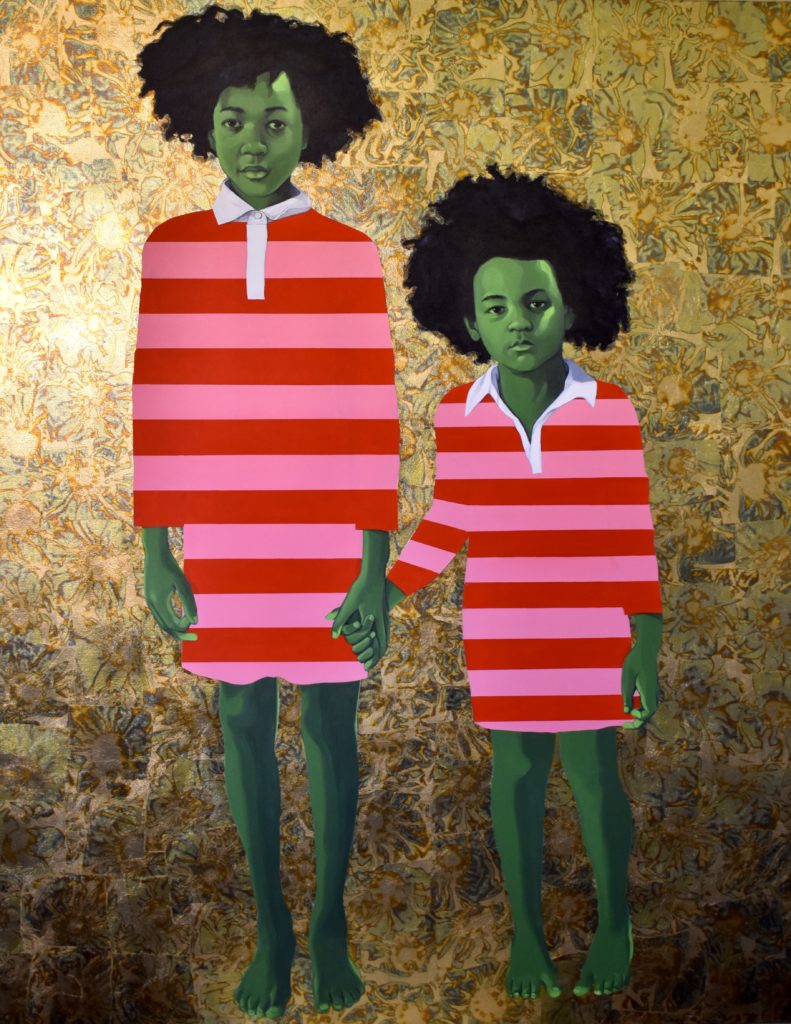

Over the course of the series, the large portraits show a story with Heyward and his family painted in green — then Heyward himself is no longer in the work. Without him, the women in the paintings become the focal point. “His family, his wife, and grandmother become more prominent. It goes from patriarchal to matriarchal. All the portraits are linked metaphorically to each other,” says Gaard.

Gaard saw some of the exhibition’s earliest pieces at Heyward’s studio a year ago when Heyward first started working on them. Gaard asked the artist if he’d hold them out of view for at least a year until CAM could make room for an entire exhibition around the work.

Along with the all-new visual art, Heyward is incorporating sound into the exhibit for the first time. The soundtrack is a mash-up of suspenseful sounds with subtle conversations between Heyward’s family happening in the background. In this interview, Heyward explains more about the inspiration behind what might be his most personal body of work.

This work was inspired by the murder of George Floyd and the conversations you found yourself having with your kids. Did you decide to start those conversations, or did they learn about his murder and bring it up?

It was twofold. I have two children, at the time one was 5 and the other 9. My oldest was watching the news and had questions. For my youngest, we approached the subject.

The pieces follow a narrative: what would happen if you were killed. That’s hard to even say out loud. How did that feel? What was that like to have yourself in the narrative then removed?

Being Black in America you have to think about it often. But to actually see it, I don’t know, it was hard. But it wasn’t super emotional, it was more practical. It was more what would happen to my wife and children. It became not thinking about myself but my family: ok do I have enough to pay off my house if I get killed?

How did your family respond to the work? Did they have questions? Did it make them sad to think about?

My wife was pretty emotional, and yes it led to conversations thinking to myself man what if it was you, how would the kids respond to not having a father? But I don’t believe there are a lot of dark pieces — I don’t want it to make people sad, I want to spark conversations.

Did going on this journey through your work affect you on a day-to-day basis?

Yes, I started thinking about doing a living will like, this could be a reality — every time you leave the house there’s a risk.

The women become more prominent after you disappear from the paintings. Can you tell us about the women in your life?

In this exhibition are both of my daughters, my wife, and my grandmother. She made it in a funny way. During COVID, I went to visit my grandmother and we got into an argument. She said, “You’re only successful because I pray for you. The Lord only hears the prayers of the righteous.” You know, I didn’t like to hear that and we got into it. I ended up making a painting speaking to that, it was my way of apologizing.

The pieces are in your signature style, but you and your family are painted green. Why is that?

That’s a reference to chrome technology in the media, a green screen. Whatever you project on it, it can be whatever you want. For me, it was shedding light on how Black people are portrayed in the media. Because of our skin, we basically walk around with a green screen, how we’re viewed depends on their perception of Black people. I actually watched George Floyd get murdered on TV. I have a portrait of me swapping him out on the green screen.

This is your first exhibition with a soundscape, can you tell us about it?

It was produced in collaboration with Jamila Davenport of Durham. It’s a minute and a half. I didn’t want to make it too long and the viewers distracted. It plays every 12 to 15 minutes, enough to hold your attention, then hear it again. No matter what you’re looking at it fits. My children and wife are talking in it. It’s snippets of what family means to us, plus police sirens, a heartbeat as a baseline, and other sounds like a neighborhood ice cream truck coming through. There are two versions.

What is family to you?

It’s having a responsibility to each other. We all have roles, even the kids. I see my role as a protector, not a provider — my wife does as much as me. I am the protector, she is the nurturer. If I’m being honest, she is the strong one, fearless, she’s the reason I’m an artist. My oldest has a responsibility to do the right thing and look out for her sister and show her what it’s like to be 9 or 10. Funny, she told me yesterday, “since you’re my Valentine, you need to take me to a restaurant.” We all play our roles in this one unit. That unit isn’t the same every day but we all know our part. It’s a well-oiled machine.

“Unseen” opens on March 19 and runs until October at CAM Raleigh.