Over the last two decades, the Boylan Heights artist has carved a niche creating intricate, nature-inspired custom home decor for her clients.

by Colony Little | photography by Joshua Steadman

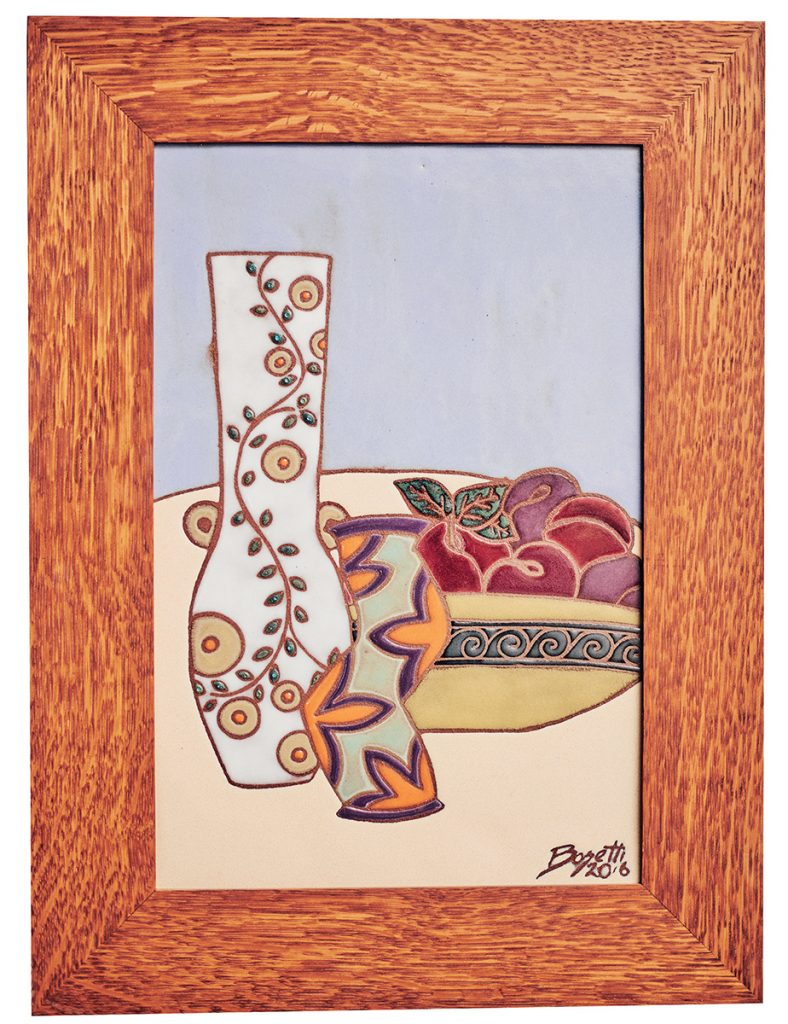

Marina Bosetti creates custom tile designs that are used for interior spaces such as kitchens and bathrooms. With a focus on elements of nature, she creates Art Nouveau-style tiles that evoke sunflower fields, tree groves, poppies and more — static ceramic pieces that capture a sense of movement, like leaves or petals blowing in the wind.

“I have two favorite flowers: sunflowers and poppies. They always look like they’re in conversation with one another. Poppies look like they’re dancing — they’re having a blast,” she says.

Bosetti was drawn to clay at an early age. Her five siblings all studied music, but Bosetti marched to the beat of her own drum, inspired more by the art classes she took. “I have a brother who’s a concert violinist, and a sister who’s a singer. Everyone in my family played an instrument but me,” she says. “I played a sewing machine.”

By adulthood, clay had found its way into her heart; she was drawn to the meditative qualities of the practice. “It just engages all of you. It’s a whole-body experience from wedging and throwing to hand building,” she says.

In glazing clay, the process of affixing gloss that helps define colors and protects pottery from wear, she found a whole new challenge that she wanted to explore more deeply. “Glazing is the hardest thing. How you glaze it is everything,” she says.

“The pot rises or fails on the glazing.” Bosetti has called Raleigh home for over 20 years. But before she moved here, she was known within pottery circles as Asheville’s “Dancing Lady,” a nod to the subjects of much of her work. From the late 1980s to early 2000s she made a name for herself selling vases under the brand name Life Forms Pottery.

During this time, Bosetti practiced Raku, a Japanese technique that involves carefully removing pottery from a kiln as it is being fired at an extremely high temperature and then submerging it into flammable organic material, like leaves or sawdust. The result creates unique patterns and textures onto the ceramic glaze.

Many of her vases of this era featured whimsical, frolicking nymphs. For her, they became symbols of joy and liberation that embodied Asheville at the time. “I was newly divorced, and Asheville had this whole celebration of feminism going on then,” she says. “The spirituality stores were selling geodes, stones, gems and incense — the dancing naked ladies fit in really well.”

After creating and selling thousands of these works, the heat-sensitive nature of Raku pottery began to take a physical toll on Bosetti in the form of cataracts (something that develops in people who work with flames). Plus, she was ready for a change both in medium and subject. “Raku is fun, but the color fades over time and it chips easily,” she says. “I wanted to do something more permanent.”

Bosetti started working with new types of clay, which presented new challenges. “Raku is a white clay body. Because there’s so much iron in red clay bodies, whites become yellow, greens become black. The amount of iron changes how they look,” she says. “It took a couple years to get it right, but I love complicated.”

Bosetti moved to Raleigh in 2001 and began working in a studio in Boylan Heights. She continued to experiment with glazing techniques on tile, investing years honing a technique loosely based on a Spanish technique called cuerda seca.

The process involves creating small wax indentations in clay that act as grout lines; these lines enable her to pour various colored glazes into small spaces without them bleeding into one another. The end result mimics the look of mosaics after the tile is fired.

With this new technique Bosetti also focused on new shapes. “When you say pottery I think mugs, casseroles, plates… I think home goods. What I do now is more like home decor,” she says, a way to help customers create personal and meaningful spaces.

With this merging of mission and technique, Bosetti created the type of work that she was looking for when she first left Asheville. And as she narrowed her focus, she earned a new nickname within the pottery community: “The Tile Lady.” She receives regular referrals by colleagues to customers who are looking to create something special and unique for their home, like a tile mural, backsplash or a fireplace mantle.

Now the complexities of clay experimentation have been replaced by the complexities of the design dialogue with her clients. The process involves an initial consultation, where Bosetti talks to her clients about the people, places, and experiences they hold dear, like a favorite flower, cherished family memory or passion project. From there Bosetti will create scaled drawings of the tile or object.

“With custom work I usually do commissions one at a time if I want to stay in the head of the customer,” she says. “I send them pictures, and they have opportunities to say, I want more of this. I want less of that, so that they can talk to me, and I’m texting with them.” It’s a process that Bosetti prefers over the pressures of larger-scale production.

Today she is in a much better position to lean into the custom work, and she credits this creative freedom to two other successful Raleigh potters, Gretchen Quinn and Liz Kelly. The two rented out space inside Bosetti’s studio for seven years, up until the pandemic.

For Bosetti, their presence not only defrayed operational costs, but brought renewed energy and activity into her practice. “I’m halfway between retirement and being the best artist I’ve ever been,” she says. “The freedom from not having to continually make things to sell allows me to be the artist I really want to be.”

Quinn now has her own pottery storefront in Five Points. “I will always be so thankful to Marina for welcoming us into that space because it was pivotal in the growth of my business,” she says. “It was like having a mentor.”

After the pandemic, Bosetti found herself alone in the studio, looking for additional ways to engage consumers and pottery enthusiasts. While she’d been teaching pottery classes in her studio for the “clay curious” for years, Bosetti found that since the pandemic, the demand for smaller, more personal classes increased.

Couples celebrating their nine-year anniversary (pottery is the traditional gift), families or groups of friends have taken advantage of quiet rainy days to book classes with Bosetti. Students receive a slab of clay that they can mold and shape into plates, bowls and trays that can be embellished with custom stamping tools.

Bosetti hopes that her students tap into the joy and wonder that she feels making her commissioned works. “All my work is intentionally happy,” she says.

“It’s always been centered around celebration.” Within Bosetti’s studio, sunflowers abound — the summer field at Dix Park is a particular source of inspiration, she says: “The way the sunflowers jut out, they’re just like, HEY! How are you?

It’s perfectly Raleigh — it’s so happy.” And it’s no surprise that the joyous sunflower plays such a prominent role in her craft, as the flower embodies the ethos of her business.

“Sunflowers create awe in people, which is what I want to create in my work,” says Bosetti. “When people see their purchase in their home, I want them to smile, I want them to breathe, I want to bring them back to now.”

This article originally appeared in the January 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.