Behind every performance of this dance company lies talent, dedication, and a deep sense of community within Raleigh.

by Hampton Williams Hofer | photography by Justin Kase Conder

Before every performance of the Carolina Ballet, Zalman Raffael drives to The Women’s Center in Boylan Heights to pick up women who are experiencing homelessness and take them to Raleigh Memorial Auditorium. There, they will see a show of arresting beauty, of mighty athletics and artistry, the work of a team of people who extend far beyond the curtain.

“Everyone deserves to feel the power of ballet,” says Raffael, the artistic director and CEO of the ballet company. This is Carolina Ballet at 25: a world-renowned company that’s not just located in Raleigh but deeply rooted here. It’s driven by a community-minded crew whose devotion to the art of ballet is matched only by their boundless talent.

Raffael — “Zali” to everyone who knows him — grew up in Manhattan. He trained at the School of American Ballet and performed with the New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theater. A prodigy of the craft, he was already dabbling in choreography by age 9. He came to Raleigh to dance with Carolina Ballet when he was 20. “When I got here, I was fascinated by the fact that a ballet company was in a place like Raleigh, where the culture of the people is very different from what I had known,” he says. Seventeen years later, he runs a critically acclaimed ballet company that has staged over 100 world-premiere ballets and grown from a budget of $1.2 million to $6 million with 38 dancers in eight programs annually.

Raffael has enamored ballet-goers with his creations for the company, including Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor, Rhapsody, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and In the Grey. He has a militant work ethic that sends him to the gym even after 12-hour studio days. “You want to have an edge,” he says. “Once you get your blood flowing, it’s easier to just keep going.” That may be in the vein of the classic obsessive ballerina, but it’s undercut by his general niceness. He loves people, and he’s committed not just to the ballet, but to the community it serves. “I believe we need one another,” Raffael says, “and we need art. It’s vital to the emotional being.”

A whole host of dancers, administrators and production team members like him have come from other states and countries to set up their lives here with Carolina Ballet. The company often spends more time in their sunny studio on Atlantic Avenue than in their own homes. “They are why I come to work every day,” says Terry Baker, the ballet’s costume director and resident costume designer. For Baker, it is literally a family affair: His husband is Carolina Ballet’s technical director.

In the large storage room that houses the light-pink pointe shoes, you’ll probably find Baker fitting each dancer with a customized pair of slippers that may last only a day or two, depending on the intensity of the choreography. “It’s a lot of up and down,” Baker says. “Even with hundreds of layers of paper and paste, the block will start to deteriorate.” He makes essentially all of the costumes in-house in the two workrooms at the studio, full of sewing machines, strewn with tulle and fabric.

He makes alterations when needed for costumes that are handed down year after year, dresses and vests that stand the tests of time — and thousands of pirouettes. Last season’s production of Romeo and Juliet featured decades-old costumes, but Baker and his team are always working on something fresh. He starts by sketching, and then his first hand of costumes, Amber Funderburk, turns the drawings into patterns. From there, the team gets sewing, bringing life from the page to the stage.

Margaret Severin-Hansen, originally from New York, has been a principal dancer with Carolina Ballet for more than 20 years, after she came to Raleigh for its inaugural season in 1998 as an 18-year-old apprentice. Severin-Hansen and fellow principal dancer Richard Krusch, who played the Princess and the Prince in Sleeping Beauty, have their own fairy tale offstage. Their 1-year-old son, Nolan, toddles around the studio and on the sets at A. J. Fletcher Opera Theater, where his parents perform. “Ballet is difficult both mentally and physically, so we rely on the ones around us to help guide and comfort us through the process,” Severin-Hansen says. “We then also can share our milestones — weddings, babies, performances. Carolina Ballet has molded me into the person I am today, both on stage and off.”

Carolina Ballet has produced some 400 different ballets; Raffael choreographed 40 of them himself. “For a regional ballet company of our age and time, these numbers are unheard of,” he says. Carolina Ballet is young enough that the initial artistic creators and founding principal dancers are still around. Many remain deeply invested: “This is how the art form survives, through the artistic team passing on the work and helping it grow with new talent,” says Raffael, who wears dance clothes to work, breaking a sweat as he demonstrates choreography. His standards are high for his dancers and himself. He’s good at being in charge, but he holds deep reverence for the ones who came before him.

The ballet itself has had ups and downs, skimming by on a shoestring budget in the early years, finding its footing in the community and then slogging through the pandemic. Raffael, the second CEO of Carolina Ballet after Robert Weiss, who started the company in 1997, is grateful for the foundation he stands upon: “It’s pretty incredible to be in a place where I watched Ricky and the board living month to month, sometimes week to week financially, and now to be in a space beyond that — it’s humbling,” Raffael says.

The founding principal ballerina of Carolina Ballet, Melissa Podcasy (who’s married to Weiss), is still in the studio every day, rehearsing with the principal women preparing for the big roles. “She was my choreographic light,” Raffael says of Podcasy, who helped mold him from dancer to choreographer. “I would discuss the relevance of movements and how things worked, and she was always right beside me.” As Raffael’s mentors, the couple gave the young choreographer the best gift: “Ricky saw me as another person with talent, and he pushed me,” Raffael says of Weiss. “He supported me in a way no one else in my life has.”

Each show presents new hurdles. The production of Macbeth called for giant bowls of fire. To keep things safe and legal, product manager Matthew Strampe fashioned a combination of steam and LED lighting for a fiery effect on stage. A recent production of Snow White featured a custom glass coffin, as well as a mirror whose frame Strampe carved himself, large enough to show a dancer on the other side of it. Both of those pieces are stored in the ballet’s warehouse in east Raleigh, where Strampe spends most of his time.

He loves the artistry of his work, the drawing and carving, the melding of engineering and sculpture. Most of all, he loves the camaraderie it all creates: “When you put up a show, you become so close to the varied group of people you’re working with, learning their stories. As someone who grew up in South Dakota, a very monocultural place, it’s the diversity that’s so appealing to me,” says Strampe, who loves the chaotic weeks leading up to shows, when he works 7 a.m. to midnight, managing crews of 20 to 50 people. “The magnitude of that teamwork is unbelievable,” he says.

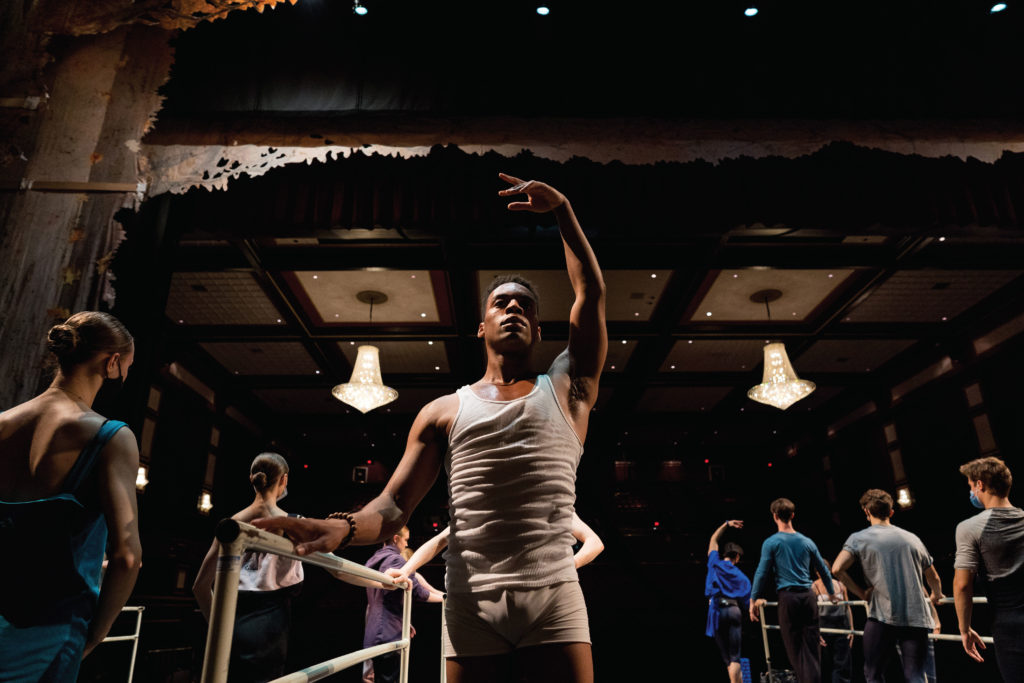

Bilal Smith, who has danced with Carolina Ballet for seven years, says that behind the scenes, the dancers and producers are just people, living their lives, doing their jobs. “We just happen to be athletes and artists at the same time. So that comes with its own level of stress and intensity,” he says. At the end of the day, they try to stay calm and focused: studying for degrees on the side, taking yoga classes, meditating or hitting a favorite burger joint.

Raffael appreciates each of the unique personalities that make his ballet work — he says there are jokesters and shy folks, nags and drama queens, lovers and leaders — they’re all part of the mosaic. He has known some of them since he was a child, like Jan Burkhard Catlin and Yevgeny Shlapko, who also trained in New York and joined Carolina Ballet along with Raffael. He’s had Catlin and Shlapko partner in the majority of his choreographed ballets. “They are my greatest inspirations,” he says with a laugh, “even though they are the biggest divas in Raleigh.”

The family is ever-extending: the founding dancers of Carolina Ballet, Pablo Javier Perez and Dameon Nagel, are now ballet masters — coaches, of sorts — who oversee large portions of the repertoire. Debra Austin, who became the first Black female principal dancer in a major American ballet company when she was with Pennsylvania Ballet in Philadelphia in 1982, is the ballet mistress. She and her husband, Romanian ballet dancer Marin Boieru, work at the School of Carolina Ballet, coaching the ballets they once danced.

Raffael opened the school in 2018 to train the next generation of dancers in a rigorous program serving everyone from preprofessionals to kids as young as 6. There’s Lilyan Vigo Ellis, the baby ballerina of the company when it all began, who danced with Carolina Ballet for 19 years. She lives nearby and is still in a seat at every show, cheering with her children.

Perhaps most acclaimed ballet companies work with such a collective effort, but for Carolina Ballet, the community extends beyond the company. Raffael has called on Victor Lytvinenko of Raleigh Denim, for example, to work together on costume designs. Raffael and Baker will sit down with Lytvinenko in what Baker calls “an explosion of ideas.” Baker will sketch out costume renderings, beginning with silhouettes. “I like to ask Zali how the music makes him feel, what emotions he’s trying to evoke. Is it dark and moody? Do we go more flowy or more streamlined? Victor will chime in on color or skirt length. He sees it all differently, looking at the aesthetics, while I’m making sure it’s danceable,” says Baker.

When Raffael was searching for ways to make the ballet more accessible to marginalized members of the community, he pulled in Molly Painter, a leader in the charge against homelessness in Raleigh. She connected him to Brace Boone III of The Women’s Center, where Raffael and other dancers now teach ballet to ladies experiencing homelessness. The women there, many of whom had never been to a performance, have taken both to the art and to the teachers. “We are so fortunate to have a community leader who recognizes the importance of including all people in the ballet,” Painter says, “and that’s Zali.”

A key for ballet accessibility lies in most people’s first introduction to ballet: The Nutcracker. Each holiday season, the merry classic draws crowds (and ticket sales) that help fund the ballet for the year, but who are also, in many cases, getting their first taste of Carolina Ballet’s magic. “The Nutcracker has been this huge thing worldwide for ballet,” Raffael says.

“It’s vital now more than ever that we build it and grow it so that people see themselves in it, that they love it.” This year’s production of the timeless tradition will boast better representation, like in the party scene at the beginning, which will include all sorts of families, with single parents and same-sex couples. The Nutcracker will be the same fairy-tale journey with improved lifestyle depictions, and it’s the pinnacle of what Raffael has done with Carolina Ballet: He has made it something for everyone.

This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of WALTER magazine.