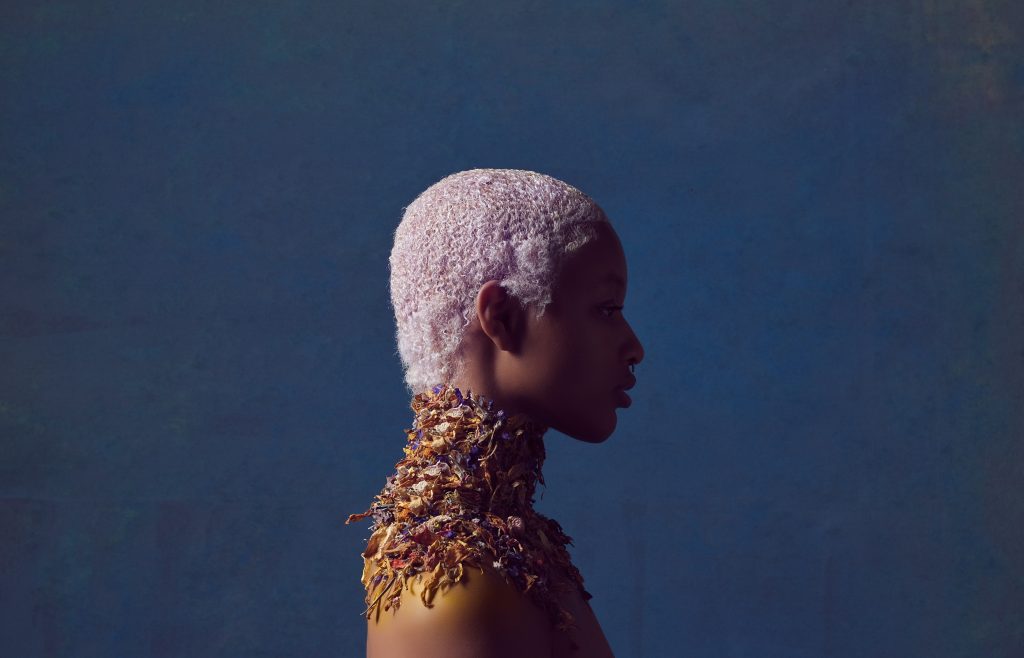

The North Carolina photographer who captured Beyoncé for British Vogue opens up about her whirlwind career.

by Colony Little | photography by Christopher Wilson

styling & flowers by Fireside Farm | Location: Haw River Ballroom

Last year, at just 21, Kennedi Carter opened her first solo exhibition, called Flexing/New Realm, at CAM Raleigh. Work from the show, which features Black subjects in Elizabethan attire reminiscent of grand manner portraiture, also won the Juror’s Choice Award in the ninth edition of the Photoville FENCE project, a national juried competition with photographers’ work displayed in outdoor exhibitions over the country.

Carter’s images have the power to soothe, seduce, transport, and transform viewers from the familiar to the unimaginable. “I’ve rarely come across a young artist as unique and passionate as Kennedi Carter,” says Rose Shoshana, who represents the artist at ROSEGALLERY in Santa Monica, California. “Kennedi has a curiosity and excitement about, not just photography, but all things relating to the world she lives in. I find her a joy to be around as her inquisitiveness is infectious and leads me down paths I haven’t previously explored.”

I first met the Durham-based photographer last summer, for an interview about Flexing. As we talked about Carter’s photographic influences, which include LaToya Ruby Frazier and Deana Lawson, she observed how their commercial work bears a strong resemblance with their fine arts photography. Creating images that harmonize both sides of the creative practice was a process that intrigued her. At the time, she set a remarkably prescient goal for herself: to accept more editorial work that could seamlessly blend into her existing portfolio.

By the fall, Carter landed one of the biggest photographic flexes of all time: an editorial shoot of Beyoncé — yes, the Beyoncé — for British Vogue. “That shoot was one of those things that just fell from the sky,” says Carter, who by the end of summer had slowly taken on some editorial work. “I was with my family a great deal and not doing much, and then I got an email asking if I was interested in doing the shoot,” she says. “I was, of course, quite interested.”

The opportunity may have felt like a stroke of luck, but in the immortal words of Oprah Winfrey: “luck is preparation meeting opportunity.” Both Beyoncé and British Vogue editor Edward Enninful were deliberate in choosing a Black female photographer for the shoot, but it was Carter’s talent for portraiture that brought the young photographer to mind.

As Beyoncé noted in her interview with Enninful about the shoot, “It takes enormous patience to rock with me.” The shoot ran long — 16 hours instead of the scheduled six — as the editors brought her through various looks. But, says Carter, balancing humble diplomacy with the unabashed excitement of a fan, “Beyoncé was really, really, really, really nice. She was an extremely good sport about it.”

Among the images from the 20-page story is one of Beyoncé in a curve-hugging, black Thierry Mugler bodysuit that’s gracefully embellished by a pair of leather stilettos. The power of Beyoncé’s pose is rivaled by an implacable gaze that bores into the viewer’s soul.

Carter’s photography landed on the cover — the youngest photographer ever to shoot a cover for the magazine — and the feature catapulted her into high demand, landing her gigs to shoot big names — Erykah Badu, Lakeith Stanfield — at national publications including Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, and Entertainment Weekly.

In a short period of time, Carter received a crash course on print publishing. “I’m slowly but surely realizing that editorial can be quite intense and at times it doesn’t pay as well,” she says. Balancing travel schedules, call times, anemic budgets, demanding personalities, and unrealistic expectations are all challenges that she recognizes as part of a business model, but Carter’s perspective extends beyond her own experiences. “I think people really underestimate how much these magazines are struggling,” she says. “So many are going from print to digital because they can’t afford the printing costs.”

Lately, Carter’s freelance work has dominated her creative schedule. In addition to her editorial work, she’s currently one of nine artists included in Google Pixel’s Creator Labs incubator for emerging photographers and directors. For this self-described homebody, frequent travel is a draining byproduct of her recent success. But it has also sharpened her focus: in the short term, Carter plans to take some well-earned time off to focus on her personal work; longer term, she’s considering going back to school to earn her MFA. “In the long run I see myself in a fine arts realm,” she says.

Born in Texas and raised in North Carolina, Carter joins a legion of southern Black image makers, including Endia Beal, Tyler Mitchell, Keith Calhoun, and Chandra McCormick, who use photography as prism to reflect the many facets of Black life. Carter’s photography captures the essence of solemnity, exploring themes of intimacy and vulnerability. Her images avoid depictions of trauma; instead they bear witness to the beauty and complexity of humanity. The strength of the gaze between her lens and her subjects punctuates her images with familiarity — with close family members and strangers alike. “I was drawn by the loving confidence, real or imagined, radiated by the people in Kennedi’s photographs,” says Gab Smith, the former director of CAM Raleigh who, among many others, played a crucial role in championing Carter’s career. “Her work in Flexing really welcomed visitors of all ages to engage with it.”

In one series, titled Ridin’ Sucka Free, Carter explores the world of Black cowboys and cowgirls in images that subvert the popular notions of cowboy culture. Trading Stetson hats and engraved silver belt buckles for contemporary adornments like a gilded Gucci belt or a satin du-rag, Carter expands our field of vision around the American cowboy. The title of the series also suggests something more: she’s not only celebrating a lifestyle, but is imagining a state of mind where free thought and independence are encouraged; where our differences are celebrated rather than judged.

In these photos, the riders enjoy the freedom to roam, explore, and express themselves in a world of their own — a guiding theme that Carter continues to interrogate in her visual art practice. “I think a lot of the ideas I look forward to pursuing in my personal work surround what a utopia looks like,” says Carter. “I think a utopia is something that is so foreign to us that we wouldn’t know how to grasp the things that would happen in it.”

An example: Knight on Fletcher St (2020), which shows a horseman from Philadelphia wearing a medieval-style chain headpiece, sitting on a chestnut-colored steed. They’re positioned on a sidewalk, against a jet-black wall. In this image, Carter plays with time, bringing elements of the past and present together to suggest a realm where these bizarre juxtapositions in style are the norm, and not an aberration. Carter plans to continue to develop this particular series, with the hopes that over time, the themes and the images will cohere as she explores various cultures around the United States. She wants to give her images time to age; her peers wait more than 10 years before issuing monographs, and she’s patient.

But while her calendar remains full, Carter relishes in quiet moments with photobooks from her ROSEGALLERY family that offer creative inspiration. “Every time I go there, Rose gives me a book,” she says. Recent favorites include Sleeping By the Mississippi by documentary photographer Alec Soth, and Carnival Strippers, a collection of images and interviews with exotic dancers from the 1970s by Susan Meiselas. This book, Carter says, takes viewers both on and off stage, giving a voice to the dancers that offers readers a different point of view of itinerant carnival workers. “With Carnival Strippers, I was interested in it because it offers a perspective that you didn’t even know existed,” says Carter. Both photographers render subjects found in society’s fringes with a thoughtful, respectful eye. “I love very raw photos, it’s helping me figure out exactly what I’m drawn to.”

Experimentation is another draw for Carter’s interest in returning to school. “I would like to get into documentaries; finding little strange stories that exist and keeping record of them,” she says. “With the images I’m hoping to make, I want them to appear a bit bizarre and strange.”

Evidence of this is found in her portfolio, among small details, slightly out of focus, that ignite further curiosity: a framed, folded American flag next to a woman wearing lace babydoll lingerie; the bloodshot eyes of a woman in a long blonde wig wearing an iridescent sequin bodysuit. These intriguing subtleties ask questions whose answers will likely take shape in narrative form through a book or zine; she’s currently working on a publication using WePresent’s editorial platform.

But for now, she’s taking it slow, allowing her images to age. And, most importantly, after months of riding this exciting wave of her career, Carter says, “I’m giving myself time to breathe.”