As this writer reflects on the death of a beloved companion, he offers a prayer for the lives that touch us… and those that await beyond.

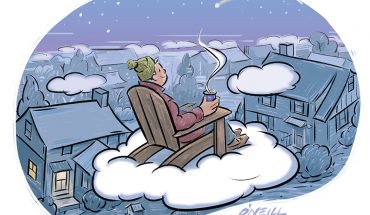

by Jim Dodson | illustration by Gerry O’Neill

On one of the last warm mornings of summer, I was watering shrubs when I heard a heavy thump behind me in the garden.

Turning around, I saw only half a dozen birds gathered at the three feeders that hang from our aged maple’s outstretched limbs. I walked over to investigate.

I found a large squirrel crawling desperately on the ground toward one of the young azaleas planted back in the spring. The critter had evidently fallen from one of the high branches and was either dazed or severely injured. As I approached, the squirrel curled up at the base of the plant and burrowed its nose under the shrub’s branches.

My first impulse was to fetch a garden tool and end the poor animal’s suffering. But long ago I made a pact with the universe to cause as little harm as possible to creatures large and small — probably from reading too many transcendental poets and Eastern sages early in life, as well as covering a great deal of murder and social mayhem during the first decade of my journalism career.

To my wife’s amusement (and sometimes horror), I’ve been known to gently escort spiders and captured houseflies to the door, return snakes to the wild and even grant the odd mosquito a reprieve to live and bother someone else another day.

Not counting the untold number of innocent garden plants I’ve inadvertently offed due to general ignorance or untimely negligence, I’ve generally abided by the naturalist maxim that it’s best to let nature take care of her own. So for this reason I went back to watering the shrubs for a spell, hoping the fallen fellow was merely stunned.

Our little patch of paradise is a remarkably peaceful kingdom. Dozens of birds dine from our feeders, which offer a perpetual challenge to the squirrels that inhabit the forest of trees around us.

Over the years, the squirrels have displayed impressive acrobatic skills and inventive ways to get at those feeders, prompting me to constantly come up with strategies to thwart their efforts.

It’s kind of a fun game we play. Fortunately for them, the birds are absurdly sloppy eaters, accounting for considerable spillage on the ground that keeps both squirrels and rabbits well fed.

When I walked back to check on the fallen squirrel, he was lying right where I left him, perfectly still. He was dead.

I picked him up to look him over. He was an older fellow, bearing scars, nicked up by life. Perhaps he’d simply lost his grip or just let go. It was impossible to know. In any case, it seemed only fitting to bury him on the spot where he lived out his final moments on this earth — underneath the young azalea.

It was my second death of the week.

Two days before, on a beautiful, rainy morning, we decided to put our beloved dog, Mulligan, to sleep.

Mully, as I call her, found me 17 years ago, a wild black pup running free just above the South Carolina state line, literally jumping into my arms as if she’d been waiting for me to come along. She was my faithful traveling companion for almost two decades.

Three days before we lost her, Mully made the daily mile-long early morning walk we’ve strolled together for over a decade. Never sick a day in her life, it was the rear legs of this gentle, soulful, brown-eyed border collie I called my “God Dog” that finally gave out.

After our walk, she hobbled painfully around the garden and settled at my feet at the bench where we sat together most evenings. Her upward gaze told me it was time for her to go. It was the hardest — but right — thing to do.

The idea of the afterlife for all God’s creatures — especially dogs — has fascinated me since I was a little kid. One of my first memories comes from a late autumn evening in 1958, when my mother and I were walking the empty beach at low tide near our cottage in Gulfport, Mississippi.

We were looking for interesting seashells washed up on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, where November storms famously coughed up a bounty. It was my first lesson in immortality.

Our dog, Amber, had just died of old age. I was sad to think I would never see her again. I wondered aloud what happens when dogs and people died. My mom picked up a perfect scalloped shell, pure alabaster white, and handed it to me.

“Tell me what you see in that shell,” she said. “Nothing,” I said. “It’s empty.” She explained it had once been the beautiful home of a living creature that no longer needed it, leaving its protective shell behind for us to find. “Where did it go?” I demanded. “Wherever sea creatures go after this life.”

“Do you mean heaven?” She nodded and smiled. I’ve never forgotten her words: “That’s where your dreams come true, buddy.”

“Same with Amber?” “Same with Amber.”

A few years later, a marvelous woman named Miss Jesse came to help heal my mom after a terrible, late-term miscarriage. I often pestered Miss Jesse in the kitchen or when she took me along to the Piggly Wiggly. One evening I asked her why all living things had to die.

She was rolling out dough and making biscuits at the time. Her rolling pin kept working. “Let me ask you something, child,” she said. “Do you remember a time when you weren’t alive?” I could not.

“That’s because you ain’t never not been alive, baby. Nothin’ you love dies. It just passes on to a new life — just like the trees in spring.”

Half a century later, I heard the voices of both my mother and Miss Jesse in a powerful song called “Take It With Me” by songwriter extraordinaire Tom Waits.

I played it the day Mully left me. I’ll play it again when I spread her ashes in the garden she helped me create. I play it, in fact, every year when the leaves begin to fall. It’s my November song. A few of the lyrics:

There ain’t no good thing ever dies

I’m gonna take it with me when I go…

The children are playing at the end of the day

Strangers are singing on our lawn

There’s got to be more than flesh and bone

All that you’ve loved is all you own.

Due to summer’s extremely dry conditions in our small corner of paradise, the leaves fell early this year.

By the time we give thanks for this year’s tender mercies, missing friends, beloved traveling companions and even the fallen squirrels that have graced our lives with their presence, they may all be safely gathered up to wait for us. Somewhere where dreams come true.

This article originally appeared in the November 2022 issue of WATLER magazine.