The sculpture Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian is a visitor favorite at the NCMA, which will host a broader range of work by the artist, who was killed on Sept. 11.

by Hampton Williams Hofer

Twenty years ago, the North Carolina Museum of Art organized an exhibition in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of the Wright Brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk. It featured more than 50 contemporary artists exploring the idea of flight, among them the late Michael Richards, whose sculpture Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian has remained on view at the NCMA ever since and has become a visitor favorite.

But a new exhibit opening March 4 provides evidence that Richards’ thematic explorations go far beyond aviation, into issues of freedom and escape, racial inequality and social injustice.

The traveling retrospective Michael Richards: Are You Down? is his largest-ever solo exhibition, showing how his work holds a contemporary relevance as uncanny as the manner of his tragic and untimely death.

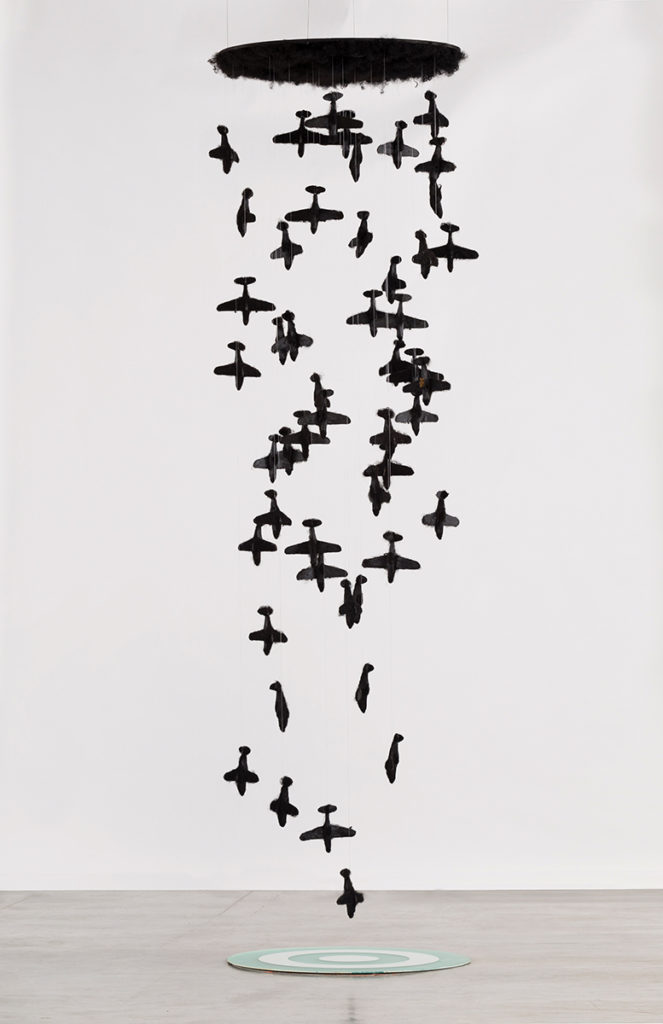

Seven feet of resin and steel, cast from Richards’ own body, Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian is a gilded figure of a pilot in uniform, suspended on a pole, his body pierced with miniature airplanes. His gaze is cast somewhere beyond the viewer.

The sculpture, like much of Richards’ work, pays tribute to the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of primarily African American fighter and bomber pilots in World War II. The title refers both to the Southern folk tale of entrapment and to the saint who was shot with arrows for refusing to deny his faith.

The sculpture is layered with allusions to spirituality, Blackness and masculinity, but the puncturing planes also became an eerie foreshadowing of Richards’ death: he was killed in his studio on the 92nd floor of the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001.

Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian, an inadvertent memorial to the artist himself, has lived at the NCMA since 2003 on long-term loan from Richards’ estate, and will be on view in the Global Contemporary Galleries this spring when Michael Richards: Are You Down? opens.

The new exhibit includes another version of Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian (Richards made two), as well as nearly all of the artwork from his most prolific decade, between 1990 and 2001.

In the exhibit is a piece called Winged, a single continuous arm consisting of two bronze casts of Richards’ own arms, joined at the elbows. On either end is a gracefully curved hand. The structure hangs from the ceiling, swaying with the air, and five cast feathers hang beneath it.

With nods to Icarus, it is literally a wingspan and metaphorically a flight arrested, a dream deferred.

And it is a favorite of the coordinating curator of this exhibit, Linda Dougherty, who is chief curator and senior curator of contemporary art at the NCMA. Another piece she expects to be a visitor favorite is Swing Lo’, a large sculpture that is a hybrid of a chariot and a lowrider car, with a blue neon wraparound and a speaker system blasting dance music.

“I think it will provide a moment of pure joy and exuberance in the galleries,” says Dougherty.

Richards was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1963 and raised in Kingston, Jamaica. He grew up between post-in-dependence Jamaica and post-Civil Rights-era America.

He came back to the United States for college, bringing cultural influences from African, African-American, Jamaican, Judeo-Christian and Greek mythological stories and traditions.

His art was filled with the language of metaphor. Heavily influenced by the Black Arts Movement of the 1970s, Richards explored African-American folklore and history, conveying tension between ascendance and descent through sculptures and installation pieces primarily in bronze.

“The power of Richards’ work is that it can be read on many different levels,” says Dougherty. “Like any great work of art, each viewer will bring their own associations, references and experiences to it, and walk away with their own interpretations.”

Richards brought together historical references and popular culture, melding the everyday and the transcendent. Using his own body to cast his sculptures, Richards connected his work to his own experience, immortalizing himself in the bronze figure of a pilot or a saint.

As curators Melissa Levin and Alex Fialho say in text accompanying the exhibit: “Inextricably connected to the moment of its making in the 1990s, Richards’ work — engaging Blackness, flight, diaspora, spirituality, police brutality and monuments — remains timely and resonant decades after its creation.”

Richards spent much of his tragically short career paying artistic tribute to the Tuskegee Airmen, whose heroism wasn’t fully recognized until long after WWII.

He described his inspiration in an undated artist’s statement: “The pilots serve as a symbol of failed transcendence, and lost faith, escaping the pull of gravity, but always forced back to the ground, lost navigators seeking home.”

The last piece Richards was known to be working on before his death was a sculpture of an airman riding a burning meteor, falling toward the Earth.

“The dream of flying,” Dougherty says, “is ultimately a wish to defy limitations, and in Richards’ work, one sees the manifestation of that desire.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.