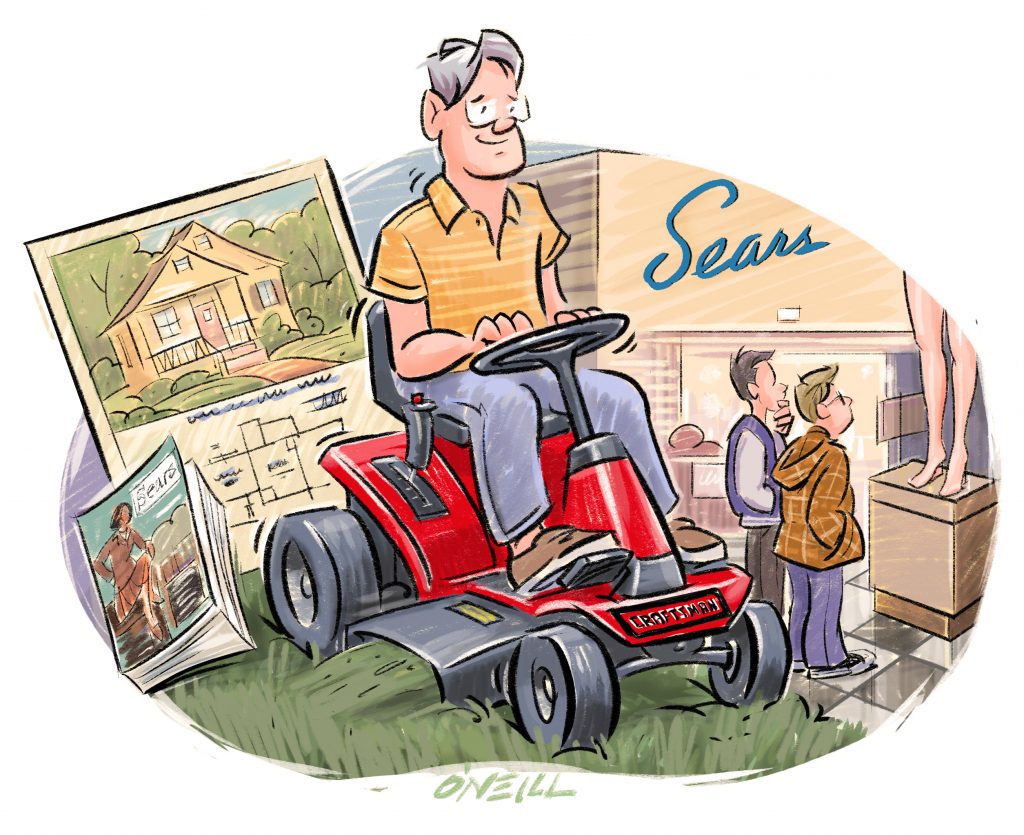

Saying a fond farewell to Sears’ last North Carolina store, where this writer got his first bike and ogled mannequins in the lingerie department.

by Jim Dodson | illustration by Gerry O’Neil

A few months ago, I learned that the last Sears department store in North Carolina was closing. So out of simple curiosity, and a dose of nostalgia, I went over to pay my respects.

Truthfully, I hadn’t set foot in our local Sears store since purchasing a new Craftsman lawnmower there more than half a decade ago. (Happy to report, it’s been a fine mower.)

Before that, I reckon my last visit to Sears was probably as a kid in the mid-1960s, fueled by its famous “Wish Book” Christmas catalog. Every kid I knew haunted the toy department at the downtown Sears retail store during the run-up weeks to the holiday.

My first bicycle came from Sears. It’s the same bike that was later parked outside the store the year my best buddy Brad and I innocently drifted from the crowded toy department into the adjacent women’s lingerie department to stare in wonder at the display mannequins in all their under-garmented glory. As the unamused clerk with the pointy-blue eyeglasses escorted us to the exit doors, she refused to believe we were simply looking for presents for our moms (a story as old as original sin).

That iconic downtown store, in any case, is now a giant hole in the ground, awaiting construction of a swanky office building. Time, life and commerce march resolutely on.

So, let’s pause and have a moment of fond reflection for — as Smithsonian recently described it — “the retail giant that taught America how to shop.”

Sears began modestly in 1887: a railway lumber salesman named Richard Sears moved to Chicago to partner with an Indiana watchmaker named Alvah Roebuck to launch a catalog selling jewelry and watches. Both men were still in their 20s.

Six years later, they incorporated as Sears, Roebuck and Company. Its cornerstone was a 500-page mail-order catalog that sold any and everything an American farmer or thrift-conscious homemaker could ask for at “fair price,” shipped directly to the customer.

In an era where most Americans still resided on farms or in small towns, Sears’ reach exploded like a prairie fire, fueling the growth of urban factories.

No less than Henry Ford was said to have studied the Sears marketing model for making and selling his cars. The company’s first stock certificates were sold in 1906. “If you picked up a big enough chunk of stock when the company went public,” writes Investopedia, “you’d never have to work again.”

The first Sears retail store opened in Chicago in 1925. Four years later, on the eve of the Great Depression, the company was operating 300 stores around the country.

By the mid-1950s, the number topped 700. By then, the corporation’s reliable Kenmore appliances, lifetime-guaranteed Craftsman tools and DieHard auto batteries were household names in America’s ballooning mass consumer culture. The stores followed the consumer’s migration from Main Street to shopping centers and, eventually, to suburban malls.

Perhaps the company’s most enduring line was introduced in 1908, when a Sears executive named Frank Kushel came up with the idea of kit houses.

They were sold through a specialty catalog called “The Book of Modern Homes and Building Plans,” offering 44 styles of mail-order homes ranging in price from $360 to $2,890. Generally shipped by rail, these house packages provided everything down to screws and nails — including pre-cut framing lumber, flooring, doorknobs, wiring and plumbing — complete with instruction booklets and all numbered for assembly by homeowner or contractor.

Through the first half of the 20th century, an estimated 75,000 Sears kit houses were shipped to Americans in every style, from Bungalow to English Cottage, Craftsman to Queen Anne. Old House Journal notes that Kushel’s Modern Home Program wielded as much impact on the development of American architecture as that of his famous contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright.

Sears boasted that its houses were built to last. And sure enough, thousands of them remain highly prized, lovingly restored jewels in older neighborhoods across America. Here in North Carolina, Raleigh, Greensboro and Charlotte each claim dozens of surviving Sears houses.

By the 1970s, the firm owned the tallest skyscraper in the world in Chicago. Sears was among the first to introduce home internet services, and jumped into the real estate, credit card and financial services.

Perhaps it was too much for the gods of commerce to tolerate.

In 1993, just shy of its 100th anniversary, Sears discontinued its famous catalog. By then, Walmart was the nation’s leading retailer, and Americans were suddenly buying things “online.” One year later, a former hedge fund guru named Jeff Bezos started up an online book service called Amazon, pretty much putting the finishing nail in the coffin of the historic Sears, Roebuck and Company brand.

As the company’s sales steadily spiraled downward, a forced marriage with K-Mart in 2004 failed to stem the hemorrhage.

In January 2017, shortly before I purchased my Craftsman mower, the iconic tool brand was sold off to Stanley Black & Decker. Less than a year later, in October 2018, Sears filed for bankruptcy.

Last December, the company emerged from bankruptcy, but announced the liquidation and closing of all its remaining stores. According to reports, less than a dozen Sears stores made it to this spring — only one in North Carolina.

Which is why, out of some strange, old fashioned sense of brand loyalty — or at least happy memories of lawn mowers, kid toys and provocative lingerie mannequins — I felt a final farewell trip to Sears was in order.

Bright yellow “Going Out of Business” banners festooned the building. I wandered through the cavernous structure looking at the remaining items. Fifty-percent bargains were everywhere: a deluxe king-size Beautyrest Black mattress for $600, a Signature Total Gym for $500.

I looked at Kenmore refrigerators, top-line Samsung dishwashers and GE Elite ovens, all half-price. I decided on a lightweight Craftsman toolbox to remember the place by, a steal at $27.

On my way out, I paused to chat with a clerk named Janice, who has worked for Sears for more than two decades. “It makes me really sad to think that Sears is going away for good,” she said. “Everything in my house as a young married woman came from Sears. I guess nothing lasts forever, does it?”

She surprised me with a sudden, feisty grin. “You know, if we’d’ve stuck with catalogs, we’d have beaten Amazon and still be going strong!” I loved her company spirit. I wished her well.

Then I went home to mow my lawn.

Whenever the math of this world doesn’t quite add up — when the sad subtractions outnumber the hopeful additions, or vice versa — I find temporary comfort by mowing my lawn. Besides, the Craftsman mower from Sears never lets me down.

This article originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.