An incredible archive at UNC Chapel Hill keeps Southern music memorabilia accessible and alive.

by David Menconi | Photography by Forrest Mason

When he first arrived at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Southern Folklife Collection in 1999, Steven Weiss found himself overwhelmed by all of its holdings: a huge trove of recordings, photos, films and ephemera. But what the collection’s new curator was most drawn to was a literal wall of sound, a line of racks holding about 7,000 mostly ancient vinyl albums covering every style imaginable.

“I used to spend a lot of time just staring at this wall,” Weiss says. “There’s so much here I’d just love to dig into, still, 23 years later. Everything in here represents a world unto itself. So many stories, I never know where to start.”

Nestled on the fourth floor of the Wilson Special Collections Library on the UNC campus (with an off-campus storage facility in Research Triangle Park to handle the overflow), the Southern Folklife Collection is one of the world’s premier music archives, with artifacts far beyond those thousands of albums. It has somewhere north of a quarter million sound recordings on cassette, reel-to-reel and 8-track tape, 78-rpm records, wire recordings and old-style cylinders, plus machines to play them all on. There are also photos, films, Andy Griffith’s guitar and the hand-painted recliner from the cover of Southern Culture on the Skids’ 1997 Plastic Seat Sweat album.

More items are coming in all the time, too, enough to keep Weiss and his small staff busy cataloging, sorting and labeling items. One of the collection’s employees is Tatiana Hargreaves, a young graduate student who is also one of her generation’s leading musicians in old-time folk, an active recording artist, and a music teacher — the perfect background for pulling together presentations from the archive on legendary elders like Elizabeth Cotten and Ola Belle Reed. “I’ve learned so much,” says Hargreaves. “I’d had some external interactions with archival recordings, listening to recordings to learn how to play them. But I didn’t know what went on in the background. I feel like I’ve just scratched the surface of the details that go into this work.”

Along with serving as a historical repository, the Southern Folklife Collection is primarily used for research. Closed during the pandemic, it’s currently open by appointment only. But even during the worst of the shutdown, researchers and record companies were making use of its materials — like the

2021 box set from Craft Recordings on folk legend Doc Watson, “Life’s Work: A Retrospective,” which was largely decorated with historical photos pulled from the collection. “The materials they provided really made all the difference to that project,” says Scott Billington, who co-produced the set. “It was impressive, just how much they had.”

The beginnings of the collection go back to the other side of the world, around 60 years ago. An Australian collector named John Edwards amassed an impressive collection of more than 2,500 American country records before he died in a 1960 car accident, and his will specified that the records be sent to America after his death. The University of California, Los Angeles was the first institution to take in the John Edwards Collection. It stayed there until the late 1980s, when UNC acquired it, combined it with its Folklore Archives, and formed the Southern Folklife Collection.

The archive has grown by leaps and bounds ever since, especially after Weiss’ arrival. Previously, he lived in Washing- ton, D.C., and worked at the National Archives and CNN’s capitol bureau. But his dream job was to run a music archive — “I always wanted to work with music archives, that’s my passion,” he says — and this turned out to be the place.

“There are maybe a dozen or so significant-sized archives in the country that do what we do,” says Jeff Place, curator of the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections at the Smithsonian in Washington. “At this point, the Southern Folklife Collection almost surpasses even the Smithsonian because of the collec- tions Steve has brought in over the years. He’s amassed a real who’s-who of the greatest figures of American vernacular music producers and collectors.”

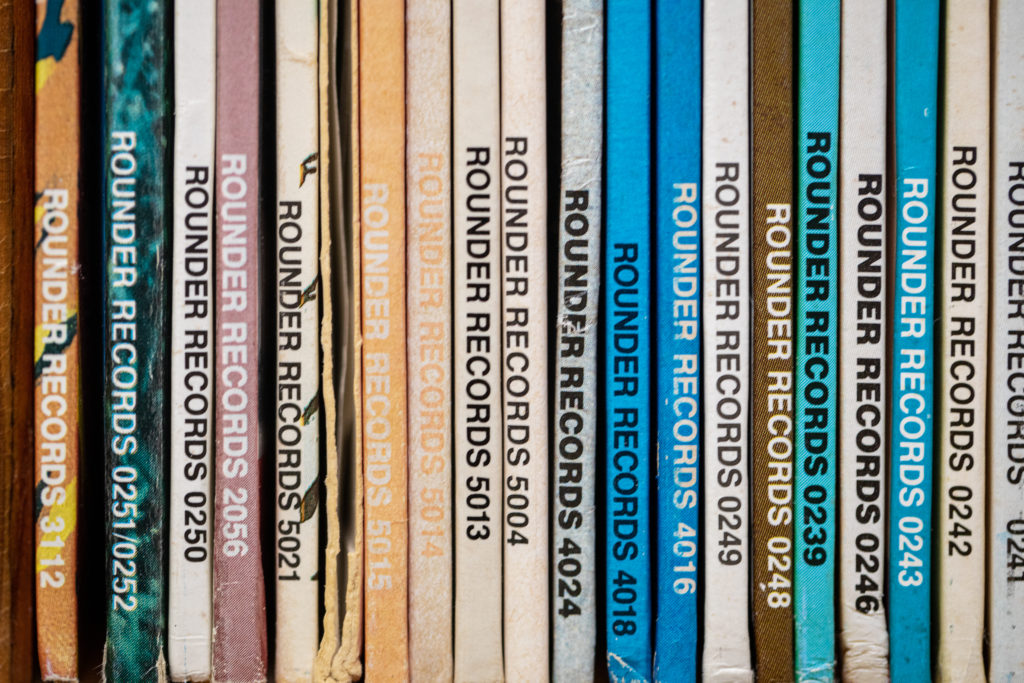

You’ll find treasures like legendary Atlantic Records producer Jerry Wexler’s record collection, the archives of the founders of the bluegrass label Rounder Records and the far-flung recordings and films of folklorist William R. Ferris. The Southern Folklife Collection helped archival label Dust-to-Digital Recordings on a 2018 Ferris box set, “Voices of Mississippi: Artists and Musicians Documented by William Ferris,” which won two Grammy awards. Another Ferris box set is in the works, compiling his films of blues artists from Mississippi.

Ferris is one of the leading folklorists in the field and could have placed his archive at any museum in the country. He chose the Southern Folklife Collection because it agreed to digitize his record- ings and films to make them available online, a project that will take years.

“That’s become more of a priority over being a dusty mothball archive where people just come to do research to write their books,” says Weiss. “It’s more active and fluid than that.”

Another priority of recent years has been to bring the collection out into the world with more public programming, since it’s not open to the public. This past spring, for example, UNC’s Carolina Performing Arts presented a “Voices of Mississippi” concert for which the the Southern Folklife Collection provided materials.

The work has not gone unnoticed among collectors, scholars, and musicians looking for final destinations to house their collections permanently. David Grisman, a renowned folk-jazz mandolinist, recently bequeathed his personal archive to the Southern Folklife Collection. Billington, who has won three Grammys over the years while producing a long string of classic Louisiana and New Orleans artists, plans to donate his work to the archives, too.

“To not have it just stuck in a box somewhere and actually available for use and research online is a pretty amazing thing,” says Billington.

__

This article originally appeared in the July 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine