The Wolfpack baseball and football legends reflect on brotherhood, college and pro athletics and life’s trials along the way.

by AJ Carr | photography by Geoff Wood

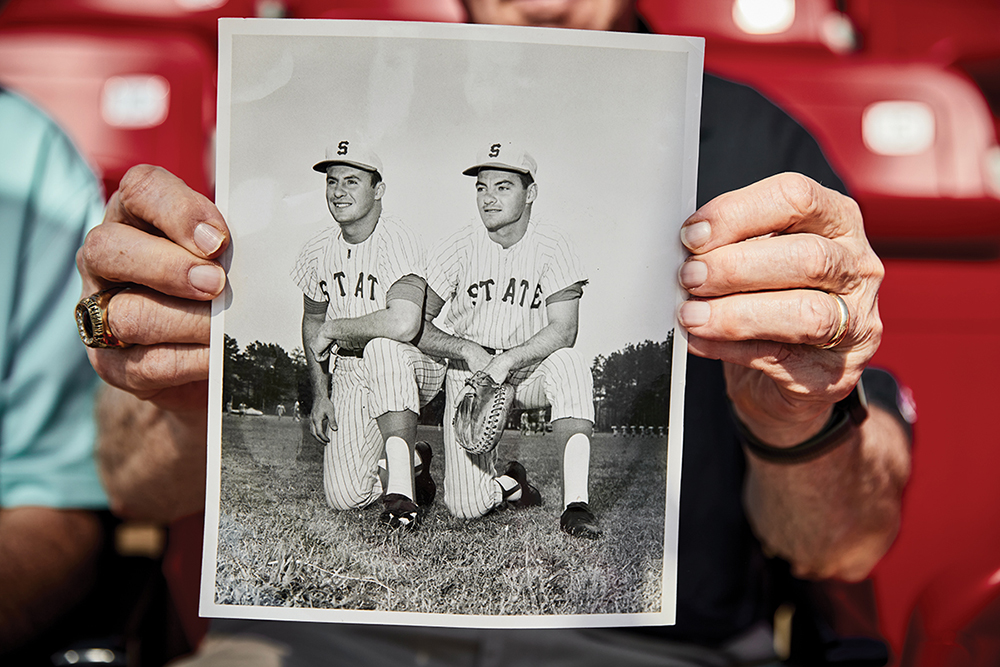

The 1968 photo of Freddie and Francis Combs kneeling side-by-side in matching North Carolina State University baseball uniforms might have lost some gloss, but its significance hasn’t dimmed with the passage of time.

More than a prized picture, it symbolizes the fraternal twins’ relationship. Born five minutes apart, they bonded early with brotherly love and a passion for sports, and have remained close for 76 years.

“Inseparable,’’ says Freddie. “It was a blessing having a twin brother and us having a love for sports.”

Spirited, competitive and strong, both were stellar athletes at Hertford’s Perquimans High, participating in football, basketball, baseball and track.

They both went on to North Carolina State University in 1965 on combination football-baseball scholarships and delivered — Freddie starring in both sports, Francis sparkling in baseball. Both earned degrees, had brief flings as pro athletes and settled in Raleigh. And both succeeded in long sales careers raised their families and continued fervently backing the Wolfpack.

The Combs’ long tourney started in Perquimans County in the 1940s, where Freddie and Francis embraced sports at an early age. As kids, they would hitchhike to a distant dock, catch a ferry and ride across Croatan Sound to play Little League baseball in Manteo.

But when they were 10 years old, their father died suddenly, leaving them heartbroken and the family financially challenged.

“We had a good mother,’’ Freddie says. “She was a strong Christian and raised us that way. But we grew up poor. We lived off Social Security and what our mother could make as a nurse helping people in their homes.”

Sports became an outlet, a place to excel. In high school, the Combs brothers became double trouble for opponents. Both earned All-Conference honors in football and baseball; Freddie earned prep All-America accolades as a halfback and defensive back.

“Freddie was the better athlete; he was faster, a tough running back, hard to bring down,” Francis says. “I was smarter — not in school, but as a quarterback who called plays, directed the defense and flashed signals as a catcher in baseball.”

Along with teammate and future Hall of Fame Big League pitcher Jim “Catfish” Hunter, the Combs brothers helped Perquimans win an eastern division football title and state baseball championship. Francis caught, while Freddie and Hunter alternated pitching and playing shortstop.

The brothers encouraged each other and challenged each other. If Freddie didn’t throw strikes, Francis would shout, “Come on! Throw the ball in here!” Freddie shot back: “You don’t ever say that to Catfish!” Francis retorted: “I don’t have too.”

Hunter was dominating, intimidating and caused batters’ knees to shake, Francis says. Freddie wasn’t as overpowering but won the vast majority of his games.

During their senior year, the twins saw their dream of playing college ball become a reality. Several schools expressed interest, but they decided NC State was the best fit for them to stay together and play together. Plus, the school offered both financial aid. “I don’t know how we could have gone to college without athletic scholarships,” says Freddie.

Ever grateful, Freddie and Francis gave NC State a big return for its investment. Freddie, a defensive back/return specialist, made first-team All-America and helped the 1967 Wolfpack gain an all-time high No. 3 national football ranking.

In the spring, both Freddie and Francis played key roles on the baseball team’s surge to a third-place finish in the 1968 College World Series.

Arriving in Raleigh, the brothers were befriended by NC State sports information director Frank Weedon, who became “like a second father” and helped them settle in away from home. The brothers even lived with him for a short time, and Freddie and Frank wound up in each other’s weddings.

Their athletic career at NC State began on freshman teams, back before first-year athletes were allowed to compete for varsity squads. Francis quarterbacked and Freddie played running back, leading all ACC freshmen in rushing.

A sinewy 165 pounds, Freddie was physical, elusive, fast. (How fast? Well, he used to catch rabbits for fun around Hertford.) “That ability was God-given,” Freddie says.

Things changed for the Combs after that first year. During the summer Francis traveled with his boyhood buddy Hunter and his Oakland A’s, occasionally pitching to the big leaguers during batting practice.

To Francis’ surprise, the NCAA ruled his participation with the A’s a violation and suspended him from playing sports the fall semester of his sophomore year.

So, Wolfpack football coach Earle Edwards told him to keep his combo scholarship and specialize in baseball, which he did. (Later, after seeing Francis’ arm strength throwing long passes around the practice field, Edwards reportedly said he wished he had encouraged him to continue playing football as well as baseball.)

Freddie, while a talented halfback, made a position change that same year, switching to defense. Turns out it was a magical move. He earned first-team All-America honors his senior year. He partially satisfied his penchant as a ball carrier by rambling 434 yards on punt returns, setting an NC State career record.

There were many memorable moments, especially in 1967. With a solid offense and defiant defense, NC State started the 1967 football season 8-0 and earned a No. 3 national ranking.

The undefeated streak included a win over the highly rated University of Houston Cougars. (They even spoiled the Cougars “victory party” the team had planned before they lost the game: Freddie and some of his Wolfpack teammates, who were staying in a nearby hotel, showed up as uninvited guests.)

A triumph over the No. 2 ranked Pennsylvania State University later in the season could have propelled the Pack to No. 1 in the polls. But undefeated NC State was stopped about a foot shy of the goal line on a late-game drive and lost 13-8. “Absolutely devastating,’’ says Freddie, still feeling the pain of that defeat 56 years later.

The Wolfpack bounced back from that loss with a prestigious 14-7 win over the University of Georgia in the Liberty Bowl, a perfect ending to a 9-2 season.

In the spring, Freddie and Francis teamed up and helped Coach Sam Esposito’s baseball team win ACC and district titles and make a strong run in the 1968 College World Series, their brightest highlights on the diamond.

Francis was a savvy, strong-armed catcher who masterfully worked with Pack pitchers. Freddie played infield and outfield positions, a baseball bandit who stole bases, and one season posted a team-leading .330 batting average.

Having achieved all that and more, the brothers are known throughout Wolfpack Nation. But Freddie says a lot of people still “don’t know we are twins.” They don’t look like twins, wear matching clothes or make anybody see double. Francis is five minutes older, taller and bigger than Freddie.

When finishing at State, Freddie was drafted to the NFL by the San Diego Chargers, but got cut in the preseason. He played two and half years for Norfolk, Virginia, in the Continental Football League before suffering a career-ending leg injury.

Francis, who had an unwavering affinity for baseball, spent three seasons in the New York Yankees’ minor-league system.

“Francis was very smart, had an accurate arm, knew how to work pitchers and call pitches,” Freddie says. “If he could have hit better, he might have made it to Triple A, maybe to the majors.”

After their pro playing days ended, when the hurrahs turned to echoes, Francis and Freddie anchored in Raleigh, got jobs, started families and have enjoyed life side by side.

Throughout the ensuing years, they’ve remained tightly tethered to the athletic program, contributing in various ways.

Francis worked as a “Spotter” with the Wolfpack Radio network for 57 years. During one stretch he attended 598 straight football games, at times having to find a ride. Most memorable is the time he hitchhiked from Raleigh to Michigan, a 30-hour excursion. When he popped into the State dressing room at Ann Arbor, the players gave him a standing ovation. Mercifully, coach Earle Edwards invited him to fly back to Raleigh on the team plane.

Francis and his wife Debbie (whom he met at State, and to whom he’s been married for 52 years), also sent State two talented baseball players — sons Ryan, a pitcher, and Chris, a pitcher, outfielder, first baseman and slugger who blasted 42 career home runs by the late 1990s. After Chris died from ALS at age 45 in 2020, the Wolfpack honored his jersey and established an award bearing his name.

“It was a thrill to see my two kids play,” Francis says. But Chris’ four-year battle against ALS was the “toughest of times.”

These days Francis, who retired after 30 years with Dillon Supply, is officiating area football, basketball and baseball games, working with NC State Radio, attending Bible Study and enjoying family time, especially with grandchildren Ann Marie, Ava and Christopher.

Freddie is in his 32nd year selling athletic equipment for Blankenship & Associates. He stays fit by working out and playing pickleball and also values family time. He and his wife Jaime, have been married for 54 years. They keep up with their daughter Kristen, grandson Quinn, and granddaughter Kahlee (each athletic in different ways).

And of course, they remain in close touch. “We talk every week,” says Francis, adding that Freddie “is always available anytime I need something, he’s always there for me — in good times and bad times.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.