Renowned artist Beverly McIver encouraged this NCCU grad to pivot from football to painting — today, he’s creating intimate, thoughtful work.

by Paul Baker | photography by Samantha Everette

Lamar Whidbee often writes his thoughts in a small sketchbook, on pages the color of cardboard. Without adding dates to the journal entries, he writes whatever comes to mind at the moment. “It could be thoughts while reading a book, or from a long day of work,” says Whidbee. “Either way, I write to understand my feelings.”

The thoughts in that notebook lead him to the canvas where, before any creation takes place, this mixed-media artist will sit in front of the materials in silence, praying and meditating. “Life, like art, seems to be a culmination of choices. It’s up to the individual to choose to persevere through defeat, agony and success,” says Whidbee.

Whidbee’s work has been exhibited at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Visual Art Exchange, Durham Art Guild, Art Center of Greenwood (South Carolina) and the Arts Center of Carrboro, as well as galleries at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Meredith University and Winston-Salem State University. He regularly works on three pieces simultaneously.

“When the ideas aren’t flowing for one piece, I can observe it while working on something else,” says Whidbee. “My current mediums include graphite, charcoal, oil pastel, acrylic paint, oil paint and thread — the variety of materials helps satisfy my desire for texture and immediacy.”

Frequently, Whidbee’s work touches on themes of family. “I create art around family because it is my truth. Family is what I connect to most,” he says. “Maybe that derives from being raised as an only child.” Whidbee grew up in rural Hertford, raised by his grandparents. A creative and curious child, Whidbee remembers following his grandfather everywhere; it was from him that he always heard the phrase “make do with what you have” — the key words being make do.

“Circumstances in life change, whether it be finances, health, environment, but the artist always finds a way to create,” Whidbee says. Whidbee left his small town and familiar environment to enroll at North Carolina Central University, a school with a long tradition of supporting artists and creatives. A gifted high school athlete, Whidbee started his college career as a wide receiver on the football team as his primary extracurricular.

It was renowned artist Beverly McIver, an endowed professor in the art department there, who shifted his focus. McIver noticed Whidbee’s talent and began to mentor him. “Lamar was a student at NCCU that showed promise and an inquisitiveness that is uncommon in many students — why I suggested he quit the football team and pursue art,” says McIver.

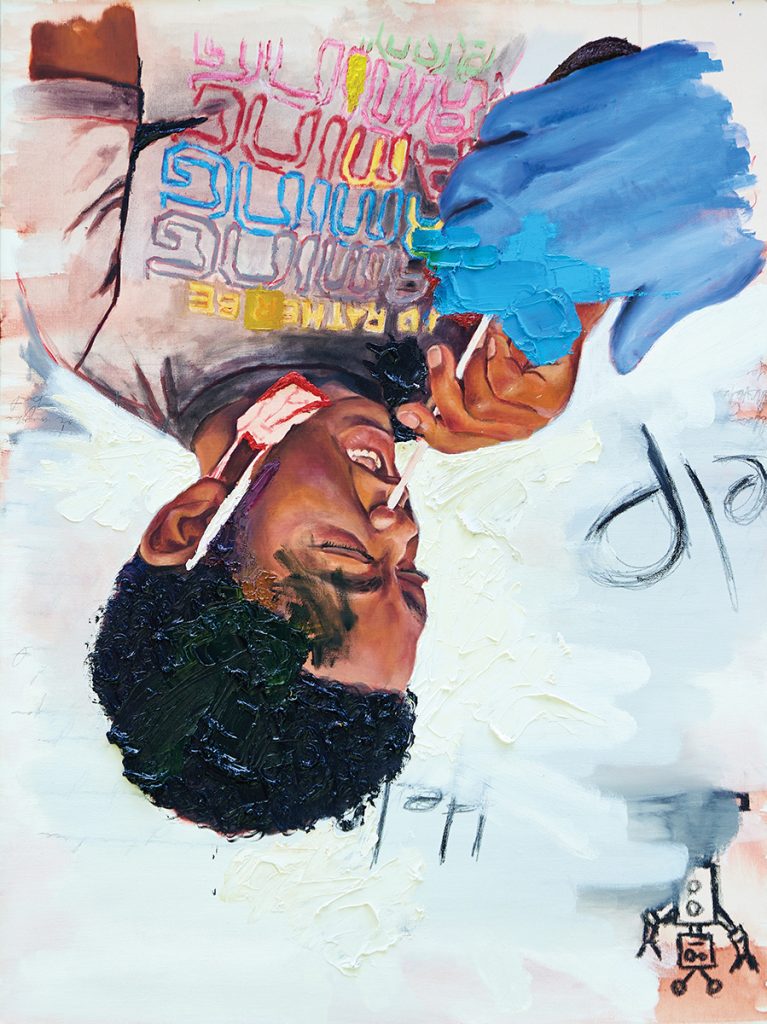

Under McIver’s tutelage, Whidbee mastered myriad painting techniques, including impasto, where paint is thickly applied to the canvas to create texture and brushstroke visibility. This technique has become a signature, bringing to life the real emotions in the faces of the people that he paints. “What I learned from her was that your intuition is normal… those thoughts and things you’d like to say, you can as an artist,” says Whidbee.

In 2011, McIver encouraged Whidbee to submit work for his first group art show, at Craven Allen Gallery in Durham. “Lamar’s work affirms the importance of having the talent coupled with a vision.

He understands that the vision may not be present immediately but reveals itself through the artistic process,” says McIver. After selling his first exhibited work, Whidbee realized he had some decisions to make around his future, and that being a full-time artist might be a possibility.

“Whidbee was a gifted student, very much dedicated and passionate about producing art. He was one of those students you would see around school, always looking for the opportunity to improve,” says Christine Perry-Espinoza, who was curator at the NCCU Museum of Art while Whidbee was a student and included his work in group shows in 2012 and 2013.

After graduating with a degree in studio art from NCCU in 2013, Whidbee went on to get an MFA from UNC-Chapel Hill and a license as a clinical mental health counselor associate from North Carolina State University.

Along the way, Whidbee also became a father; he and his wife, Sanailer, have two children, Stone and Star, and now live in Knightdale. Whidbee almost always brings his children to see his art exhibited, even if only to see themselves on museum walls — they often serve as muses for his work. One piece, Footsteps, captures Stone walking in his father’s shoes.

It’s an approachable piece, done with humor, relatability and a casual tone. Another mixed-media work, Covid Baby, features Star getting swabbed for a Covid test, with a look of both compliance and annoyance that many parents will recall from the pandemic.

These two pieces are included in Daddy’s Home, an exhibit currently on view at CAM that Whidbee debuted at Artspace during a studio residency as a Jo Ann Williams Fellow. It examines the realities, value and pride of fatherhood through the African American lens, specifically “the impact the decisions my father had on my own approach to fatherhood,” says Whidbee.

Incorporating traditional materials such as pencil, canvas and paint, he also used found materials, such as cardboard. “I used this disposable substrate purposely,” he says. “Growing up a little boy of color, I sometimes felt that the world viewed me as disposable.”

And yet, the artwork in Daddy’s Home exudes safety, security and unspoken love — values that he learned from his grandparents and practices with his own family. “I saw firsthand a father figure that was transparent, caring and protective,” he says.

That thoughtful approach underscores a parallel practice as an art therapist. Whidbee works with individuals and couples to express emotion through painting and has written a children’s book, 1 2 3 4 Breathe, inspired by the square-breathing technique to encourage mindful practices.

“Lamar wears many hats: artist, father, husband, counselor, change agent and most remarkably, student,” says Raj Bunnag, curator of exhibitions at CAM and a fellow UNC MFA. “He is always eager to learn more while navigating the journey of an artist.”

Whidbee continues to exhibit in both solo shows and group exhibitions around the country. In 2022, he exhibited along with his mentor, McIver, in Full Circle at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art. He’s found himself part of a growing community of young artists of color in North Carolina making their mark.

“There is a communal pride of Lamar and everyone is eagerly awaiting to see where his art will take him,” says Perry-Espinoza, who is now curator of exhibitions at the Spelman College Museum of Art in Atlanta. Bunnag agrees: “Lamar is an artist with more than just talent; his work speaks to the experiences of underrepresented communities transcending race, demographics and gender.”

Ever thoughtful, but humble, Whidbee’s focus is much narrower. “Consciously, I rarely think about legacy in my work,” says Whidbee. “I believe that art is created just as a person’s life is — on a daily basis. But if my art leaves a mark on someone’s life, I’m grateful that my interactions with my family have been part of their process.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.