After his passing, A.C. Snow’s daughter finds the diary he kept during his time as a young soldier in the Pacific Islands.

By Katherine Snow Smith | Photography by Bryan Regan

A few weeks after my father died in January, at the age of 97, I met him again as a 19-year-old.

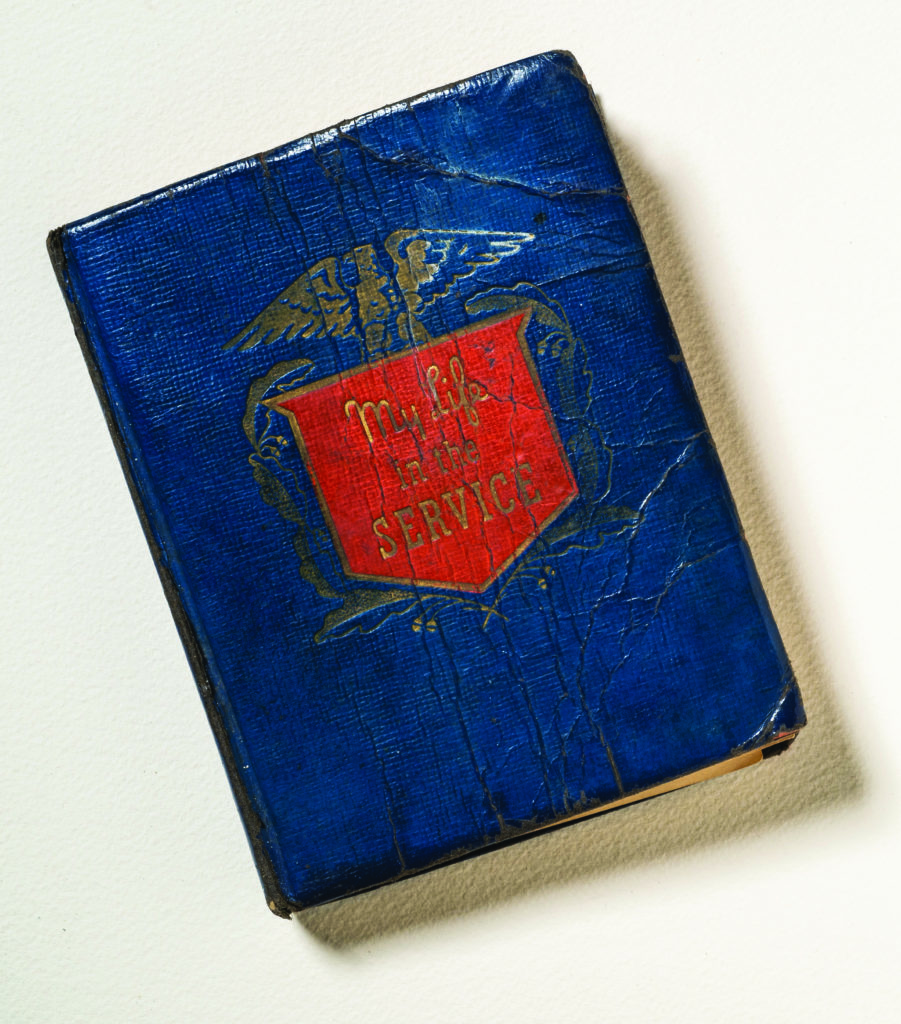

Stacked under a file of important letters and a few issues of Sports Illustrated with the Tar Heels on the cover was the journal he kept from his time in World War II. In the handwriting I recognize so well, the journal is filled with his eloquent way of describing scenes of life that many people, certainly most teenagers, tend to overlook.

My father, A.C. Snow, was drafted about a year after graduating from Dobson High School in Surry County. He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps, which was the aerial warfare component of the Army that later became the Air Force. For a long time, he was stationed on New Guinea, where his squadron built much of the Milne Bay base after the Allies occupied the large island and fought against the Japanese for four years to maintain control.

I grew up knowing him as a supportive and loving father, then later understood more of his role as the editor of The Raleigh Times and longtime columnist for that paper, as well as The News & Observer. But reading his journal, I glimpsed into his young mind — and got a firsthand look at the lives of so many of that Greatest Generation.

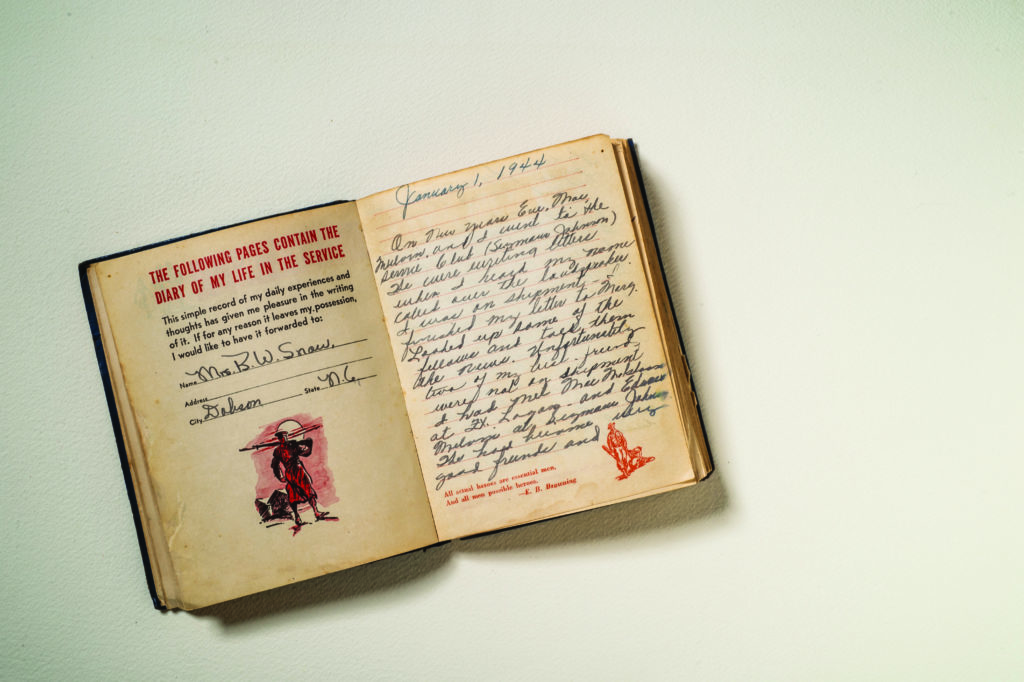

My Aunt Ima, one of my father’s 15 siblings, is listed on the first page as the person who gave him the journal. Its template has an upbeat tone, akin to something I might have sent my kids when they were at Camp Seafarer or Sea Gull. Many pages have prompts like, “My Buddies in the Service,” “Officers I Have Met,” “Gifts I Have Received,” and “Autographs.”

It stopped short of saying: “War Can Be Fun!”

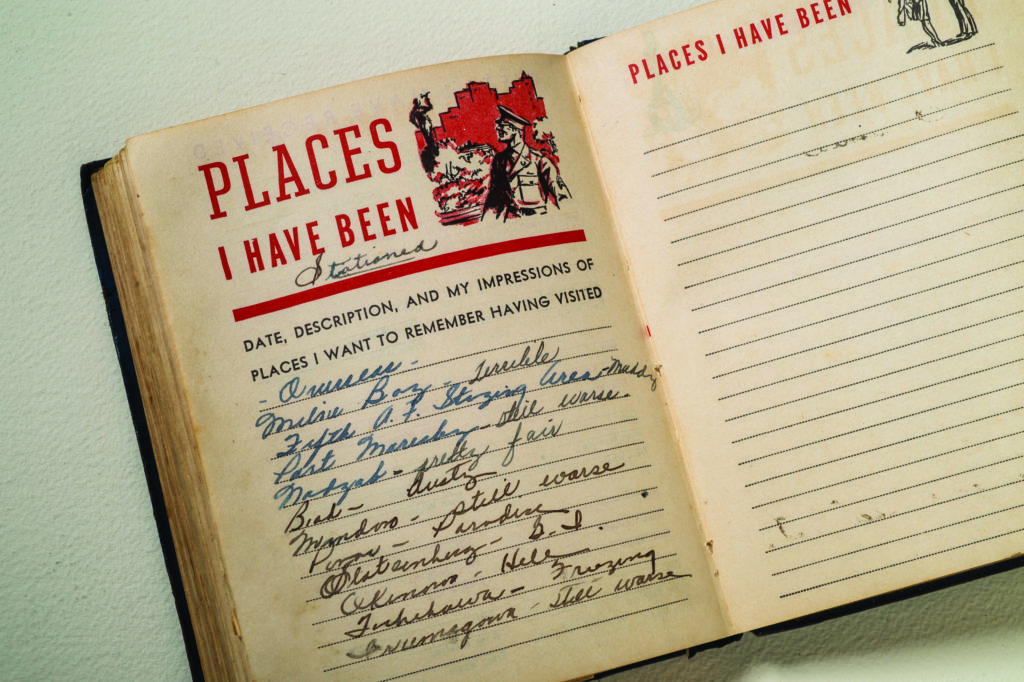

There are postage-stamp sized sketches of jolly servicemen playing the harmonica, waving to pals, or shaking hands with a lovely woman, alongside inspiring quotes from Shakespeare, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Bible. On the page eliciting “Places I Have Been,” with a sketch of a serviceman on a city street, my father added the word “Stationed.” He lists nine islands in the South Pacific with one-word descriptions such as “terrible,” “still worse,” and “muddy.” He calls Okinawa “hell.” The island of Pugo receives the only high marks: “paradise.”

He was at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in Goldsboro when he learned, on Dec. 31, 1943, that he was being shipped out.

Jan. 1, 1944: I never thought I’d really go.

He left a week later for California and would travel west for eight days to reach the Pacific Ocean. Until then, he’d never even gone five hours east to see the Atlantic.

Jan. 6, 1944: The morning of Jan. 6 about 400 soldiers were gathered at the Parade Ground with packs and gas masks. We shivered in the early morning dampness until 10 o’ clock when we began to march to the railroad accompanied by a big band.

Once he reached Pittsburg, California, he and the other men boarded a barge to the USS Monticello troop carrier, which would transport them across the Pacific for 18 days.

Jan. 14, 1944: Civilians waved goodbye. I was impressed by an old man and gray haired woman standing together waving frantically. The fellows laughed. But I knew that these two old people were sincere in their emotions.

Jan. 17, 1944: From 10:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. we are allowed on deck. The hours we look forward to each day. Usually Charlie, Don and I just stare at the endless ocean and discuss anything and everything. These are the shortest hours of the day. The heat is blistering but at least we get some fresh air. Twice today we spotted ships and the alarm was given, but I was relieved to find they were Allies.

On Feb. 3, they reached land — New Guinea.

Feb. 3, 1944: We were all elated and thronged to the deck… It looked very green and jungle like. We had thought all along we were going to Australia. Not one of us had ever even heard of this place and not one had any desire to get off here… We reached the shore. Two abreast we started marching, expecting to be massacred by [Japanese soldiers] at any moment. After walking an hour a truck came along and picked us up. We jostled along for 15 miles and finally stopped. We piled off and were led down to a row of tents. Some fellow asked me where I was from and I was so tired and discouraged I announced: ‘America’ at which he mumbled ‘smart guy.’ …No one had told us a thing and we knew not what to expect.

They set up their cots in waist-high grass and were attacked by ants the first night. The next morning they cleared the grass, killed the colossal ant colonies, and soon learned what to expect for a while.

Feb. 8, 1945: Some days we work 4 p.m. to midnight. Others from 11 p.m. to 8 a.m. We work every day, Sundays and all. We unload ships, work with cranes, clear the jungle, build latrines and everything else imaginable.

But the journal also recorded some brighter moments. Going to a church service was a treat, as was a Betty Grable movie, or the chance to wash their clothes in a creek on the first afternoon off in three weeks. He noted when he received letters from relatives, friends, and even teachers, writing that he’d read them “over and over again.”

Feb. 4, 1944: The sun arose from behind a nearby mountain. It was a crimson ball of fire which turned the cloudless sky into a spectrum of colors. The tall leaves of the coconut palms seemed to be waxed, and the water in the bay shimmered in the early dawn while the jungle birds awakened and began screaming and flying about.

March 12, 1945: One time Don, Charlie and I worked in a warehouse and did nothing but race up and down on loading machines… We had movies three nights a week. The theater was only logs lined up on a hill surrounded by the jungle with the screen up front. Natives climbed the trees at the edge of the jungle and watched the miracles of movies. The Red Cross did a swell job. They furnished us with lemonade.

Ultimately, my father was assigned to Communications, which included working with secret codes, manning the switchboard, and flying with pilots to retrieve soldiers or take supplies. He was never in direct combat; he had it easier than many. But he was still exposed to danger, and the death of others, regularly. He wrote that “guns roared” all around as Japan tried to take over New Guinea.

May 16, 1944: I watched the crew of a B-24 jump out of their plane. Heard the pilot over the radio receiver. He put the automatic pilot on. It flew into the clouds to be later shot down.

Sep. 6, 1944: My good friend and fellow student Logan has been killed. He’s the first of our [high school] class to die and the last, I hope.

Sep. 27, 1944: A 171 [fighter squadron] crashed. 9 people killed. Lt. Jameson, Nash Fredericks and Dale Garrett were killed. The whole tent went to the funeral.

My father’s family was fortunate. Three of his brothers and four of his nephews served in World War II. They all came back home.

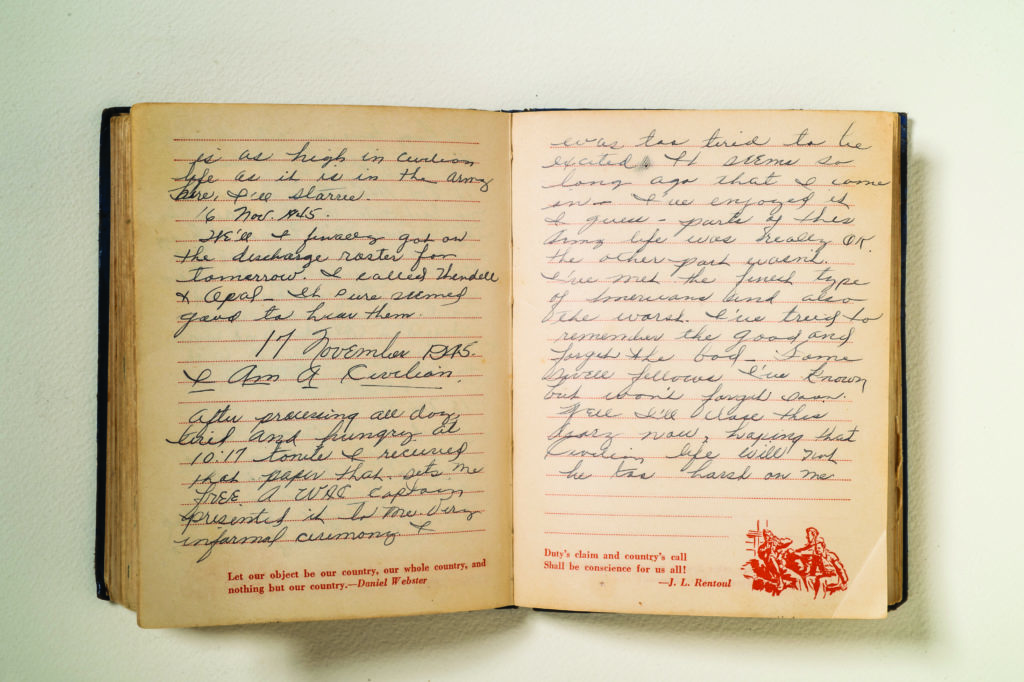

Nov. 17, 1945, Fort Bragg: I am a civilian! At 10:17 tonight I received the papers that set me free… It seems so long ago that I came in. Parts of this Army life were really ok. Other parts weren’t. I’ve met the finest type of Americans. I’ve tried to remember the good and forget the bad. Well, I’ll close this now, hoping that Civilian life will not be too harsh on me.

He didn’t know what to expect when he left or when he returned. But he was hopeful. And this, of course, is why the 16 million men and 350,000 women who fought in World War II are considered “the Greatest Generation.” They fought and worked in extreme heat and cold, survived on mediocre food, and found solace in their friendships and occasional, simple pleasures.

As I read this well-worn journal that seemed to offer some small comfort as my father waded through the war, I thought of my own son, who is also 19. How different his life as a freshman at Denison University in Ohio is from that of my father at the same age.

The same day that I read my father’s journal, I received an email from Denison for parents of first-year students. It alerted us that our students would soon be choosing housing and roommates for next year and warned us this can be a stressful time. It offered tips for supporting them as they make decisions.

I do appreciate a faculty that keeps parents in the loop and cares about students. But it’s impossible not to compare this life with my father’s, and the millions like him.

Uncle Sam didn’t tell my father where he was going, much less let his mother know or suggest ways to make the transition easier. My son and I can text, call, or email and reach each other immediately. My father and his mom exchanged letters that took months to arrive.

My dad didn’t talk much about World War II. Being a soldier wasn’t what defined him. But I think those two years that capped off his hardscrabble upbringing definitely helped shape him. He learned to always appreciate the small things, a trait he carried through to the end.

And perhaps it was this first collection of writing — two years of tedium, fear, and wonder chronicled in a journal — that ignited what he would refer to, 75 years later, as “a love affair with words and their wondrous power when strung together.”

__

This article originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine.