Equal parts athleticism and theatrics, professional wrestling had its heyday in the 1980s — but still attracts an ardent and colorful following.

by Billy Warden | photography by Bryan Regan

One mid-1960s afternoon, WRAL-TV founder and noted opera aficionado A.J. Fletcher lifted his eyes from the bouffant-haired executive assistant with whom he had been conversing to behold… a giant.

Parading through the front doors of his office was Haystacks Calhoun, also known in the pro wrestling ring as “The Country Boy” — all 6-foot-4, 600 pounds of him.

Legend has it that a gobsmacked Fletcher remarked: “I do believe, Miss Mildred, that is the largest human being I have ever laid eyes upon.”

Calhoun was used to astonished stares, in addition to cheers and jeers. For nearly three decades, he — along with such volcanic contenders as Rowdy Roddy Piper, “The American Dream” Dusty Rhodes and “The Russian Bear” Ivan Koloff — played a part in a thumping and thriving “rassling” circuit that included WRAL’s studio, nearby Dorton Arena and the coliseums in Greensboro and Charlotte, along with smaller, sweatier venues rumbling on their foundations around the Carolinas and in Virginia. “The roster of talent was stacked,” says Austin Idol, aka “The Universal Heartthrob.”

They all worked for the ambitious, Charlotte-based Jim Crockett Promotions. Launched in 1931, the company’s titular founder and his heirs steadily stitched together the National Wrestling Alliance’s mid-Atlantic circuit.

By early 1960s, and through much of the ‘80s, this carnival of clobber clamored into WRAL to tape a weekly syndicated TV spectacular and associated promos. It was common for grapplers to tumble through 10 shows in seven days.

“Guys were making $7,000 a week, but it was tough,” says Idol, who wrestled in the region during the early 1980s and now runs a wrestling college in Greenville, South Carolina, where he’s also a motivational speaker. “Between the travel and matches and getting to the gym, the days could be 14 hours long.”

Every Wednesday afternoon, a crew would set up the wrestling ring in WRAL’s Studio A, complete with mat boards designed to give a little and clatter loudly when giants like Calhoun, Blackjack Mulligan or Andre the Giant took a spill. Two sets of bleachers — the kind found in schools everywhere — lined one side of the ring.

Packing the bleachers was a cast as colorful as the wrestlers: little old ladies with a flair for foul-mouthed curses, Cub Scout troops, country folks in the big city to see the stars up close, church groups, even orderlies with patients.

“There was a group that came every week from Dorothea Dix when it was a mental health hospital,” says Clarence Williams, who rose from rookie camera operator to director. “I always thought it was a strange kind of therapy. There were students from NC State who took great joy in harassing different bad guys — like they would the opponents at a basketball game.”

The mayhem occasionally inspired spectators to join the fray. “I’ve seen a fan jump in the ring — a few people, actually,” says Williams. “We had to hire a Raleigh police officer to be on standby in case anyone tried to attack a wrestler, which was crazy because those wrestlers could kill you.”

The TV tapings were free, but space was limited. Fans had to write in for tickets. To ensure a plum spot for ogling the pandemonium, diehard devotee Bruce Mitchell from University of North Carolina Greensboro and pals passed themselves off as a church youth club in the early ‘80s. He wore a bright green polyester suit to make sure he showed up on the TV screen.

“The mid-Atlantic became the most lucrative wrestling promotion in the world in that mid-’70s to early-’80s heyday,” says Mitchell, who went on to become both an elementary school teacher and a celebrated pro wrestling columnist and podcaster. “Those wrestlers were some of the best performers in the world.”

The balletic bruisers delivered a handful of iconic wrestling moments at WRAL. The most squirm-inducing one might have been Greg “The Hammer” Valentine breaking Chief Wahoo McDaniel’s leg in 1977. For months afterwards, a gloating Valentine taunted McDaniel, setting up a blockbuster series of revenge bouts.

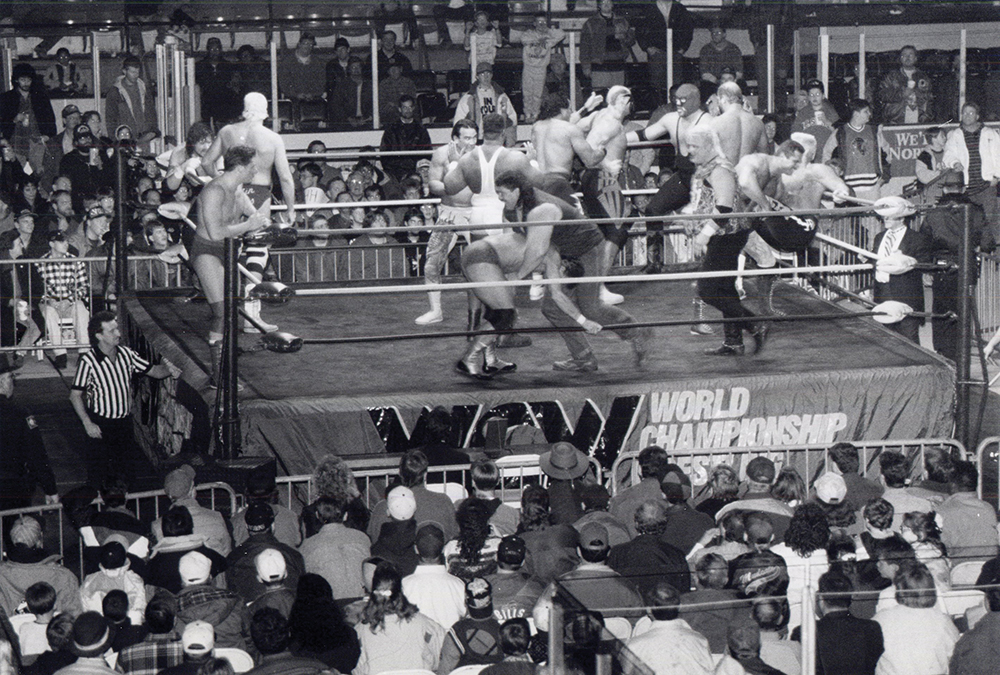

Indeed, the TV tapings were mostly a riot of sound and fury designed to sell tickets to the marquee matches at nearby Dorton Arena. The most magnificent of those occurred during a roiling thunderstorm in 1985, when the beloved “stylin’ and profilin’” “Nature Boy” Ric Flair took down a peacocking imposter daring to tout himself as “The REAL Nature Boy.” Fans filled every seat, as well as the concourse egresses.

“Dorton Arena was always a great place for wrestling,” recalls Mitchell. “The moon would shine in those high windows. The ring was in the middle of the place with just one big light shining down on it. It was magic.”

Today, Crockett Promotions is long gone and the wrestling business transformed. The big-spending World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) based in the northeast has stomped out many of its more sizable competitors.

Now a throng of pint-sized promotions dot the mid-Atlantic region. The most colorful of the local efforts is GOUGE Wrestling, famed for outlandish characters and antics, i.e. “gimmicks.”

On a recent Saturday, North Carolina grapplers Glamour Boy Khan, Sideshow Phil and Sammy Love arrive with little fanfare at Raleigh’s Clouds Brewing as a bantering crew sets up a ring on the patio. There are no blinking broadcast cameras or stacks of bleachers or echoing arena rafters. Still, the performers and several dozen fans seem pumped.

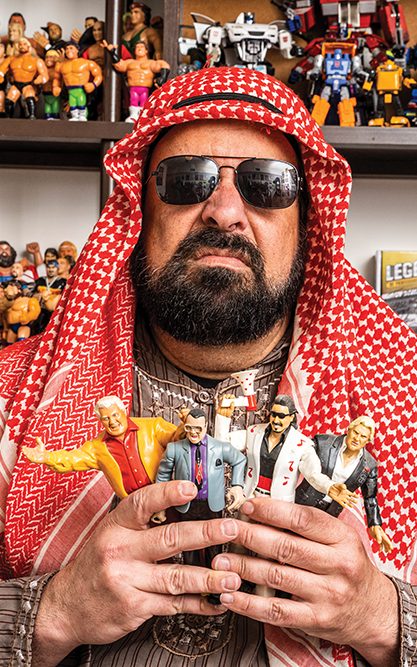

In a few minutes, bearded and burly Corey Blevins will take the “squared circle” — as fans call the ring — as Inuit Joe, a heel who’ll resort to any lowdown dirty trick to retain the GOUGE championship. (For those who don’t know: a “heel” is pro wrestling lingo for the bad guy. The good guy is a “baby face.”) But for now, Blevins, a logistics specialist by day, is happy to chat at a quiet table.

“I was missing something as a kid,” he says, recalling how he came to a side career wrangling grown men into headlocks. “I grew up without a dad. I was in front of the TV a lot, looking for role models.”

He found them in wrestling’s larger-than-life characters and teeth-rattling morality plays. Fascinated by the lore of the bygone mid-Atlantic circuit, he sought out video stores that stocked vintage tapes of the era’s biggest matches, motoring up to two hours to rent them.

“It’s Shakespeare in tights,” he says. “It’s all the best elements of sports, plus the storylines of great movies.” So, while the taproom might seem a far cry from Dorton Arena, the primal allure of “rassling” not only battles on but grips new devotees.

Near the ring, a 7-year-old girl in a pink sweater stakes out a picnic table. Asked why she’s here, her eyes narrow. The answer is perfectly obvious: “To see people get hurt and then go cryin’ to their mommas.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of Walter magazine.