After decades of neglect, one neighborhood led the charge to revitalize a park built for Raleigh’s Black families.

by Courtney Napier | photography by Terrence Jones

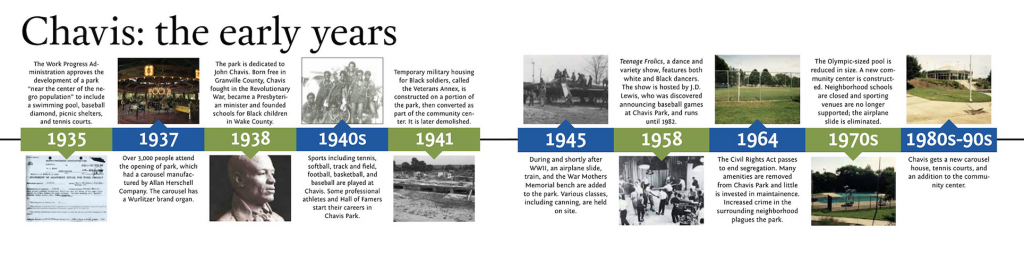

When John Chavis Memorial Park opened in 1937, it was truly a celebration. Over 3,000 people arrived at the lush, 24-acre attraction for its opening, and the excitement in the air was palpable. Music from the Wurlitzer organ inside the handcrafted carousel mingled with the laughter of children; splashes rang from the pool as teens dropped into the water like cannonballs. Black men, women, and children, dressed in their Sunday best, ate bountiful picnics on colorful blankets, bright like wildflowers on a field.

The park was immediately embraced by not just Raleigh’s families, but families from across the Piedmont region. Sundays were for after-church picnics; during the week, young people played sports like baseball and swimming and watched band practice in the evenings. Saturdays were for dancing. “We would take jazz, tap, and ballet at the community center under Mrs. Pecolia Jones. And Mrs. Copeland was our swim instructor,” says Virginia Talley, who grew up nearby in Chavis Heights. “This place was a safe haven. It was a place that we could call a home away from home.”

Despite the joy it brought to guests, Chavis Park was less a gift and more a mandate.

As racial segregation became more prominent after the turn of the 20th century, Raleigh’s city council no longer wanted Black residents visiting the existing Pullen Park. They saw the creation of a new park in the “Black side of town” as a solution to rising fears of race-mixing among Raleigh’s white residents.

The saga of Chavis Park mirrors the story of the American South: it encompasses the promise of emancipation and the horrors of Jim Crow. It contains the complicated history of progress through the Works Progress Administration (WPA) program and, nearly 70 years later, the HOPE VI Project.

And on June 12, Chavis Park started a new chapter of its story: one that honors the resilience and perseverance of the Black community in the face of it all.

A “Suitable” Space

During Reconstruction and the years following, Black and white Raleighites often lived separately but shopped, played, and even worked alongside each other. Pullen Park, founded in 1887 as a sprawling amusement destination, welcomed all of Raleigh’s families for many years, in the same way that Black and white business owners worked beside each other on Fayetteville Street, the city’s main thoroughfare.

But by 1900, white supremacist forces at the state and local level ushered in the Jim Crow era. This affected every corner of Raleigh’s society, including Black families’ access to public spaces. Pullen Park was never fully segregated, but it was against North Carolina law for Black and white people to swim together in public pools. As racial tensions mounted over the course of decades, Black families felt less and less welcome at Raleigh’s first amusement park.

Looking to dig the country out of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created a massive infrastructure and jobs program entitled the Works Progress Administration. Cities desperate to employ their residents and fund languishing projects implored the administration for help, and in Raleigh, white politicians and residents believed they needed a separate park specifically for the city’s Black residents. In 1935, state senator Carroll Weathers of Wake County, a major proponent of Chavis Park, had this to say:

“…[w]e now possess adequate park facilities for white people at Pullen Park. Obviously, there should be adequate and proper provision for a suitable park for the colored race. I think that the Public Park for Negroes would be of infinite value in affording the proper means for recreation of Negro children … Furthermore, it seems to me that having a suitable Public Park for Negroes in the Eastern section of our city would remove the necessity of attempting to provide facilities for both races at Pullen Park. Thus Pullen Park could be devoted to recreational activities for white people solely, which seems a wise course.”

Two years later, WPA began the project to create “recreational facilities near the center of the Negro population and midway between two Negro colleges.” The public park would include a swimming pool, baseball diamond, tennis courts, and other amenities.

The “Negro Park,” as Chavis Park was referred to during contruction, was built on the site of the demolished North Carolina Institution of Education for the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind, which had served the state’s disabled Black children. With a budget of $66,267.07 (down from the $130,000 investment initially requested by the city’s director of public works), Raleigh broke ground in 1936. On July 4 of 1937, the Negro Park celebrated its grand opening, but the Black community had already begun to make the park its own — starting with the name.

Earlier that year, a group of Black residents petitioned the Raleigh City Council to hold a contest among the community to choose the name of the new park. According to the National Historical Registration Application, “The Negro Citizen’s Committee of Raleigh, NC [a precursor to the present-day Wake Citizen’s Association] petitioned the City of Raleigh to rename the park for John Chavis (c.1763 -1838).”

John Chavis was a free Black man born in Oxford, North Carolina. He fought in the Revolutionary War, and then became a minister, teacher, and activist, opening several schools where both Black and white children learned throughout Wake and Orange Counties. The park’s connection to Chavis was a strong signal to the city about how Black residents wished to be seen: liberated, accomplished, intelligent, and empowered.

A Lively Park

Despite its complicated origins, the park was embraced by Black North Carolinians from Raleigh and the surrounding counties. None, however, enjoyed the park more than the residents of the South Park neighborhood and the families of nearby Chavis Heights, Raleigh’s oldest public housing project. Also funded by the WPA, the apartment complex opened its doors shortly after the park was completed. The families that lived in Chavis Heights were of modest means, but they were also dedicated to their neighbors and were proud of their community.

“In Chavis Heights, we had apartment homes,” says Virginia Talley. She stresses the word “homes” because the apartments were well-furnished and pleasant. A child of the 1950s, most of the recreational activities Talley took part in were connected to Chavis Park, just across the street from the apartment complex.

Talley and the other neighborhood children grew up having free reign of the park, almost an extension of their own front yards. Former Chavis Heights resident Linda Graham remembers wanting to spend all her time at the park as a young child. She’d even sneak over there alone without her mother knowing. “I would make sure to get back home before she did, though,” she says with a chuckle, “Because if I got caught, I would hear about it.”

As the children became teenagers, Chavis Park’s activities grew with them. Teenage Frolics, a popular show featuring the music and dancing of Black teenagers, which was filmed at the Chavis Park Community Center, debuted on WRAL’s Channel 5 in 1958. Hosted by J.D. Lewis, and billed by the station as “a live and lively dancing party featuring colored teenagers from high schools in the Channel 5 area,” the show was a pioneer in Black television, preceding Soul Train by thirteen years. Young people from all over the city, but especially the South Park neighborhood, were featured on the show as they danced along to the music of chart-topping acts like Lou Rawls and Issac Hayes. During its 25-year run, Lewis broke racial boundaries in television while creating a space for Raleigh’s Black teenagers to have fun and feel accepted at a time when school integration left many feeling displaced and unwanted in the classroom.

Eventually, however, the changes to society reached the beloved park. After the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which banned segregation and other race-based discrimination, cities all over the South that had invested in “separate but equal” facilities now felt there was no need to fund these spaces. Parks like Chavis, and the communities they held together, began to fall into ruin.

Like many predominantly Black neighborhoods and towns across the country, disinvestment of public dollars in parks, the closure of many Black public schools, and the expansion of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Wilmington Street took a toll on the South Park neighborhood. In the 1990s, after decades of neglect, the federally backed HOPE VI Project demolished the Chavis Heights apartments to make way for new, mixed-income housing. Families that had lived and played in the community for generations were displaced. Many never returned to the area once the reconstruction was complete; the people who had enjoyed the park the most were gone.

Pushing Back

In 2007, longtime South Park resident Ms. Frances Lonnette Williams was informed by a Raleigh City Council member about the city’s plans for John Chavis Memorial Park. “Have you heard about the plan for a new aquatic multiplex?” the former councilman said. The city had commissioned a study to determine where it could build a new state-of-the-art aquatic center, and Chavis Park was a top contender.

“Say what?” replied Williams, in shock. She followed with one of her signature expressions — “Nuh uh!” — and that was the beginning of a community effort that would stretch out for over a decade. She brought the issue to her community through her neighborhood association, the South Park-East Raleigh Neighborhood Association (SPERNA), and they, along with the Central Citizens Advisory Council, petitioned the City Council about their aspirations for the park in December 2019. The group wanted to see the park restored, much like the city had done over the lifespan of neighboring Pullen Park.

Those first meetings were met with questions — and outright disbelief. “One council member questioned if there really had been a train and a swimming pool at Chavis Park,” reflects Williams, referencing two beloved attractions that were removed from the park in the 1970s. In reality, many of Raleigh’s white residents had never been to or even heard of Chavis Park; its location in what was considered an undesirable part of town made it easy to overlook. Pullen Park, by contrast, had just begun a $6 million renovation of its aquatic center. The next time Williams came to a council meeting, she brought photographs and documents to prove that the park had once been as spectacular as she described.

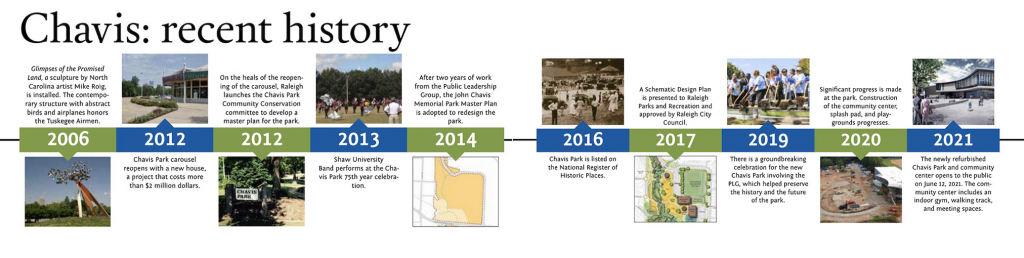

A Public Leadership Group (PLG) composed of community members, including Frances Lonnette Williams, Mary Brooks, and Virginia Talley, was appointed by the city council in 2012 and worked together for two years to revise the John Chavis Memorial Park Master Plan. The success of the community engagement process — as well as North Carolina State University professor Kofi Boone’s innovative use of cell phones to record oral history — attracted Landscape Architecture Magazine for a feature on the park in 2015.

Two years after SPERNA’s first efforts, city council voted unanimously to adopt the new master plan. The main features of the plan were determining what messages and elements were essential to the park, and outlining the phases in which they would be brought to life. Raleigh residents approved a $15 million bond to begin the first phase, promising money for the later phases would come from an upcoming parks bond. In the spring of 2016, another victory: Chavis Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places, which ensured that it will remain a permanent fixture in the city.

But for the next five years, not a single pile of dirt moved. Complications with the bidding process and lack of unity on council were just some of the issues that plagued the project. Even when meetings did occur, communities were often selecting from options predetermined by staff members who had met in earlier, separate conversations. But Williams and SPERNA persisted through continuous meetings with Raleigh council members and staff inside and outside of City Hall. Finally, in September 2019, the city broke ground to begin construction on the first phase of Chavis Park’s renovations.

The June 12 reopening of Chavis Park introduced phase one of construction. The renovations include a state-of-the-art community center, artistic homages to the neighborhood’s past, an elevated walking track, basketball courts, event spaces, and a new playground with a splash pad. The carousel house, home of the original carousel and organ, has been renovated; it’s now a community rental space equipped with a warming kitchen and restrooms. The next phases of the park will include the return of the swimming pool and a dedicated center to honor the history of John Chavis, the park, and Raleigh’s Black community entitled Heritage Plaza.

“There were at least 50 public meetings and presentations during the planning and design process for the Chavis community center,” said Raleigh’s Parks and Recreation director, Oscar Carmona, regarding the extensive planning process. The project drew many stakeholders in its seven-year process, including SPERNA, the Chavis Park Circle of Friends, NC State, and Shaw University, along with other institutions and neighbors. Their input was reflected in the 2014 John Chavis Memorial Park Revised Master Plan, as well as the John Chavis Memorial Park Cultural Heritage Plan finalized this February.

In addition to input on amenities, the community was also integral to choosing the historic, cultural, and artistic pieces that would be featured around the park. Residents chose artist David Wilson to bring the history and culture of Chavis Park and the surrounding neighborhoods to life through innovative interpretive panels — large glass panels etched with a collage of historical text and imagery — that stand throughout the new community center.

Wilson has experience capturing the historic contributions of Black communities throughout North Carolina, with past partnerships including the Black Wall Street mural at Phoenix Square in Durham, the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Arts + Culture in Charlotte, and the Kinston Music Park. “There’s something special about hearing an elder recalling their days as a youth at the park or a new community member expressing their desire to want to learn more of a culture that may not reflect theirs,” says Wilson. “These are the real moments that drive the creative process and inspire me to create a work that the community can be proud of.”

Throughout the process, Wilson felt fully embraced by the South Park community and supported by the city of Raleigh’s public art department. “I enjoyed every moment!” he says.

Eyvonne Dailey, a member of the social group Chavis Park Circle of Friends, shared her hope that phases two and three of Chavis Park’s revitalization go smoothly, something that Carmona is hopeful for as well. “My goal is to get these projects on a quicker timeline to completion, so everybody can see the work that they’ve put in over the years,” Carmona says.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

As the first phase of Chavis Park neared completion at the end of April, the Parks and Recreation staff invited Raleigh residents to the old community center for a last hurrah before it was demolished.

The weeklong event, called The Memory Tour, consisted of six exhibition rooms representing the eight decades of Chavis Park’s history from the 1930s up to the present day. “We had the unique opportunity to tell eighty years of history through storytelling, movement, and interactive exhibitions where people can hear, see, and reflect,” says Grady Bussey, the new director of Chavis Park Community Center. “It created the ambiance which Chavis Park was known for.”

In each room, guests were greeted by the sights and sounds of various eras of the park’s existence. Large posters with photos, newspaper clippings, and old maps hung from the ceiling, alongside artifacts from the park like retired horse figurines from the carousel and sports jerseys. The display transported attendees from one decade to the next. Community members stretched out their arms to point out familiar faces as fond memories of childhoods spent in Chavis Park flooded their minds.

Many of the community members who used the park in its heyday will be able to enjoy it again now — and their efforts toward its revitalization will make it available to the next generation, too. “This park will impact the folks that were here when the work first started,” says Dailey. “Those of us who are still here will be thinking about our friends on the committee who have passed along the way.”

Williams walked slowly into the exhibition after her personal tour of the new community center. “It is awesome!” she said. “All of our hard work paid off.” After catching her breath, she took it all in: the homage to the past, and the facilities of the future.

Click to expand images.

This story originally appeared in our July 2021 issue.

Pingback: Afro-Conscious Media » Saving Chavis: The History of Chavis Memorial Park – WALTER Magazine