by Ann Brooke Raynal

photographs by Juli Leonard

As drivers whiz down I-40, heading into Raleigh, a glance to the right will reveal a green swath, vivid evidence that the region’s agricultural roots are alive and well.

Thanks to miles of farmland just outside (and, in a few cases, inside) the city, Raleighites have ready access to locally grown fresh fruits and vegetables, meats, and dairy products. Decades ago, that was unremarkable. But now, we’re lucky to be able to call ourselves locovores.

Nowhere is this more deliciously evident than in the bumper crop of local ice cream makers taking happy advantage of the bounty around us. The college kid scooping ice cream made by local outfits like Lumpy’s, Howling Cow, or Fresh Local is dipping into something that had its beginnings in the grassy fields that dot the Triangle. A simple scoop can represent our history, our present, and our future.

We lucky Raleighites can have our cones and eat them, too.

With his broad back, bulging arm muscles and handlebar mustache, Buck Buchanan calls to mind a circus strongman, or Wallace Stevens’ famous poem about the triumph of life over death: “Call the roller of big cigars/ the muscular one, and bid him whip/ In kitchen cups concupiscent curds/. . . . The only emperor is the emperor of ice cream.”

Whipping up “concupiscent curds” in his kitchen is what Buchanan, 49, has been busy doing the last several years. A chef by training, he took a year off to study ice cream making. “I read every book,” he says. Determined to use local grass-fed cows, fresh ingredients grown nearby, and to make his ice cream in small batches, Buchanan started Lumpy’s Ice Cream 11 years ago. He began with a handcart, which he took to events all over Raleigh. Later he added a truck. Demand continued to grow, and a little over a year ago, he opened a store in Wake Forest. Until then, Lumpy’s was truly “home-made” in his kitchen. Now it’s “hand-made” at the store. The process remains the same.

There’s a saying that the perfect is the enemy of the good. Buchanan’s theory is that “good is the enemy of best,” and he strives for best: “The best cows. The best ingredients. I taste every batch. I adjust the flavor myself. My hands are all in it.” Buchanan even makes his own extracts, grinding vanilla beans, for example, for the perfect vanilla flavor. It’s a difference you can taste.

“I know the strawberry farmer, I know the peach farmer. The pecan farmer. I love supporting my neighbors. There are so many reasons to go local.” Buchanan buys his ice cream base from Maple View farm in Hillsborough. Maple View cows are grass-fed on pesticide-free pasture, and they are given no hormones or antibiotics.

Buchanan takes Maple View’s pure combination of cream, milk and sugar and turns it into ice cream with flavors like Chocolate Peanut Butter, Denise’s Chocolate Brownie, and the very popular Bacon and Bourbon. Buchanan grins. “Flavors change at my whim; that’s the fun of it!”

His store, which has the look and feel of a 1950s soda shop, reflects a similar spirit. T-shirts boasting “Body by Lumpy’s” are for sale, and flavors are written on the chalkboard above the counter.

It’s not Buchanan’s first establishment. A self-described “military brat from all over,” he owned a restaurant in Vermont before moving to North Carolina 17 years ago. He loves the area. “It’s home,” he says. “But anywhere my wife is, is home.” His children attend Raleigh Charter High School and Ligon Middle School, and sometimes the Lumpy’s truck can be spotted in the Ligon carpool line.

Buchanan’s latest project goes beyond ice cream. He’s seeking permission for a community garden near Lumpy’s. “I want to see a harvest table outside where we can give away fresh produce to people in need,” he says. “And, even better, teach them to grow their own food.” Buchanan has spoken to local chefs who would be interested in teaching basic cooking classes. “Give a man a meal and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to plant a garden. . . . Well, you know,” he laughs.

What’s the best part of his job? “I love my job,” he says. “There is no best part. It’s all the best. I work with and serve the best people I know. I get to make ice cream. How can anything be bad?”

Agricultural roots

“It never gets old,” says Carl Hollifield, as he gobbles up a cup of Howling Cow brand Pecan Crunch ice cream. An Asheville native and N.C. State graduate, he has been helping his alma mater turn university-owned grass and cows into university-made milk and ice cream for a decade. The fruits of his labor are sweet – but not widely known.

“It never gets old,” says Carl Hollifield, as he gobbles up a cup of Howling Cow brand Pecan Crunch ice cream. An Asheville native and N.C. State graduate, he has been helping his alma mater turn university-owned grass and cows into university-made milk and ice cream for a decade. The fruits of his labor are sweet – but not widely known.

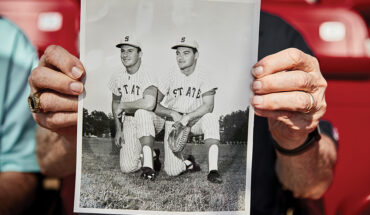

N.C. State’s proud legacy as a land-grant university is at work here: Wolfpackers been making and selling ice cream for more than 50 years.

The university owns the local land, the 170-odd cows, the state-of-the art milking parlor, and the center where 10,000 gallons of milk are processed each week. Student research takes place at every phase, beginning with the grass, and money made from milk and ice cream goes back into that research: The enterprise is completely self-supporting.

But unless one eats in the dining halls on campus, or has stood in line for a cone at the state fair, chances are Howling Cow ice cream is not a household name.

Thanks to Hollifield, 33, and the folks he works, that’s about to change. A business and marketing manager at N.C. State’s Department of Food Science, Hollifield helped come up with the ice cream’s brand name, designed its logo, and is now set to spread its frozen cheer. “Working here is a delight,” says Hollifield. Tall and thin, with eyes as large and dark as a Jersey cow’s, he’s unmistakably a man who has found his calling. “There’s always something new going on, something multi-dimensional.”

As part of a planned multi-million dollar Dairy Food and Education Center near Schaub Hall on campus, N.C. State envisions a ground-floor creamery and café with seating for 100.

The new center – for which $1 million of a needed $4 million has been raised – will have many dimensions. In addition to its public face, the center will house a training and learning center for every facet of food product development.

Though he has had a big hand in it, Hollifield says he wouldn’t have predicted this kind of growth 10 years ago. Then, there wasn’t the widespread demand there is today for locally sourced food; the center, he says, reflects the changing face of the dairy industry and will be a catalyst for more change and development.

The history behind Howling Cow is long. Though the Department of Food Science was established in 1961, the university began processing milk long before that. In the 1910s, N.C. State made the first pasteurized milk in North Carolina for World War I-era Polk Army Base in Butner.

These days, Howling Cow milk is distributed all over campus and to state agencies. Thanks to a 2004 exemption to the Umstead Act, which prohibits publicly funded industries from competing with private business, N.C. State is allowed to sell Howling Cow to the public on campus and at the State Fair.

Luckily, the campus is a big place, and one that seems to be getting bigger all the time. The Common Grounds Café & Creamery at the Hunt Library on Centennial Campus is a new venue for Howling Cow cones.

As Hollifield considers new ways to spread the word, he takes another bite of Pecan Crunch, closes his eyes slowly, and smiles: “I love my job.”

When Brett Hillman, 50, was 17 and working at a Blimpies in Chester, N.Y., his life and his life’s work changed in an afternoon. A pretty girl named Ellen from the Carvel ice cream store nearby came in for lunch and handed him a coupon for a free cone as she left. Hillman knew a good thing when he saw it. The free cone turned into dinner. Dinner turned into marriage. And Ellen’s job at Carvel turned into a career for both of them. A year after they met, Ellen and Brett Hillman bought the Carvel franchise. They were both 18.

After 30 years in the ice cream business, first as a Carvel franchise owners, and then as the owners of their own store, Hillman and his wife (who works for the U.S. Postal Service) moved to North Carolina and in 2011 took over Fresh Local Ice Cream in Glenwood Avenue’s Oak Park shopping center.

“We wanted a longer summer,” he explains. Raleigh offered eight months of pleasant outdoor time, and so much more: local organic farms, a thriving economy, and a true community. Business has been brisk; two years ago Hillman was able to remodel and expand the store.

The name of the business says it all: fresh, local. The decision was both a personal preference and a response to consumer demand. “It’s what people want. They’re savvy. They want a fresh product.” The ice-cream base comes from Jackson Dairy farm in Dunn, a small all-natural dairy that delivers daily. And that’s how Hillman makes the ice cream: daily. A scoop of his famous ‘Peanut Butter Cup” in its recyclable container is usually only hours old.

Hillman describes the store as a “sanctuary,” a place where people come to visit with one another, to forget their problems and worries. “It’s such a happy place,” he says. “One of my greatest pleasures is getting to know the families who come to the store again and again. Evening is the best time. The kids lick their cones and play corn hole. People strum guitars out here on the picnic tables. It’s idyllic.

“I love my job,” he says.

Hmm. Sounds familiar.