In her new book The Devil at His Elbow: Alex Murdaugh and the Fall of a Southern Dynasty, reporter Valerie Bauerlein explains the deep roots of the infamous South Carolina murders.

by Liza Roberts | photography by Alex Boerner

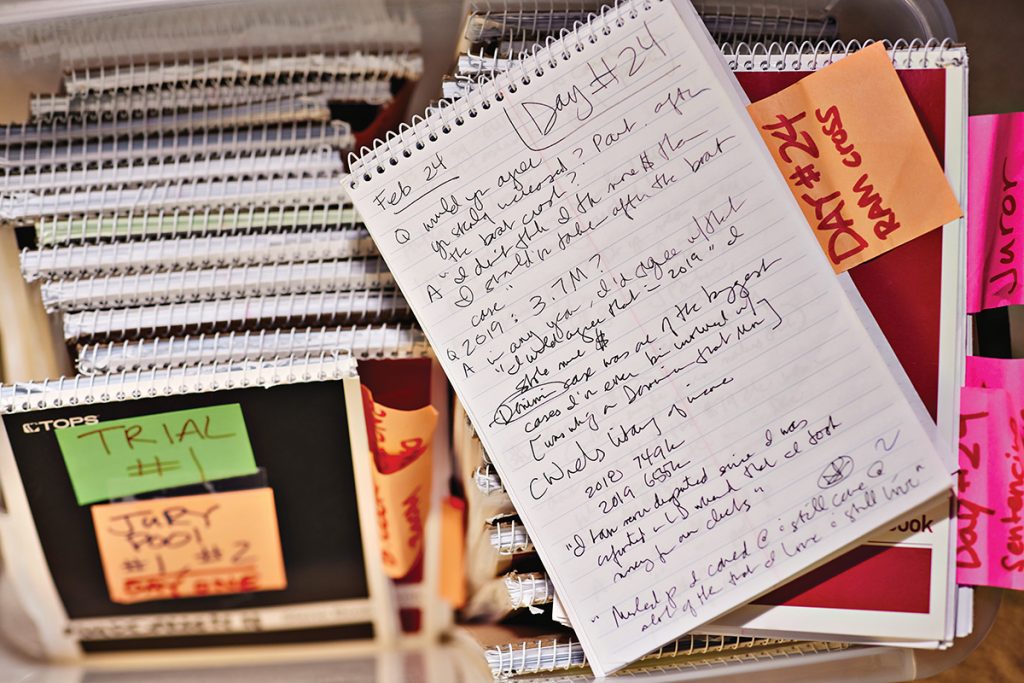

In March 2023, powerful South Carolina lawyer Alex Murdaugh was convicted of murdering his 22-year-old son, Paul, and his wife, Maggie. The journalist regularly breaking news on the story was Raleigh resident and Wall Street Journal national reporter Valerie Bauerlein. Some of her front-page features on the Murdaugh murders were among the paper’s most widely read of the year; she also became an on-camera authority for NBC’s Dateline and for a Netflix documentary.

Now, Bauerlein’s new book on the case, The Devil at His Elbow: Alex Murdaugh and the Fall of a Southern Dynasty, is out. It’s equal parts crime story, character study, cultural history and family saga. Through meticulous research, she tells the story of four generations of Murdaughs, connecting the dots to show how Alex inherited his role as partner in the family law firm as well as his sense of infallibility, lawlessness and entitlement.

Bauerlein has been covering the South for almost 30 years, including 19 at the Journal, four at Columbia, South Carolina’s The State, and a year at The News & Observer. She is a graduate of Duke University and lives in Raleigh with her husband and two children.

At what point did you realize that this was the biggest story of your career, at least so far?

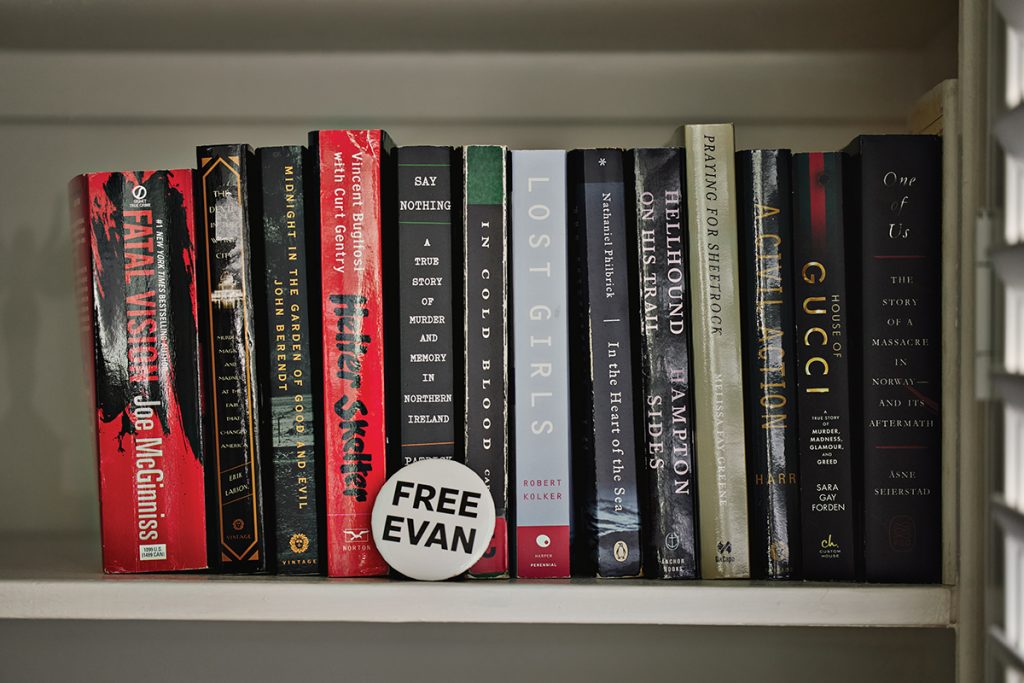

I remember my old editor at the other WSJ, the Winston-Salem Journal, saying to me: The next big crime story that happens in the South, just jump on it. See what’s there. It could be Bitter Blood or Fatal Vision. I sort of laughed it off.

And then I was following this case, because I follow South Carolina pretty closely [as part of her job covering the South], and my editor at the Wall Street Journal just happened to say: Are you following this? And I said, yeah, of course I am. I asked him: What’s the Wall Street Journal version of the story? What larger thing does it tell us? And he said, It’s just a good story. And he was right. But it was also a story about money and power.

Then the more I got into it, I realized pretty quickly it was a story that I’ve been observing for 20 years in the South — about the way that power works and the way relationships work, particularly in the small towns where I came from or where I used to work. I studied South Carolina politics for years [as a reporter] so I could try to understand how rural barons operate, how the system works. So pretty early on, I knew it was a big story, that it illuminates something about us. But I had no idea just how big. My first trip down [to Hampton, the crime scene] was in July of 2021. The homicides had been on June 7. Murdaugh wasn’t charged for a year after the homicides.

I expected the book to be a crime story, but it’s bigger than that. You make a well-researched case that he did not squander the family legacy — He actually fulfilled its destiny.

Alex Murdaugh was the perfect distillation of what the family had been building for generations. Dynasties inevitably break down on the fourth and fifth generation. Alex is the fourth, [his children] Paul and Buster are the fifth. It was inevitable. All of the rot was coming from inside the house.

It started with Alex’s great grandfather, an extraordinary human being who made a critical turn at a moment when he was dying and he had lost everything by driving to his death in front of an oncoming train to enable his children to sue the railroad. He’d done things the right way and then he made a moral turn. And then you get into his grandfather. He’s coming out of the Depression, when there’s nothing in the rural South, there’s no economy to speak of. He rebuilds an empire based on racketeering, taking advantage of others and subverting the law he’s supposed to take care of. And then his son, Alex’s father, kind of perpetuates that. Alex is the perfect distillation of it.

But I do think the difference with Alex and his forebears is that he had little inclination to use his power for good.

When did you realize the need to go so deep, to learn so much about the family, its heritage, its inheritance?

Necessity is the mother of invention. I sold the book before he was even charged, so the pitch was: There’s a story in this family. Even if he’s never charged with anything, there is something in the water in Hampton County that is creating this dynasty.

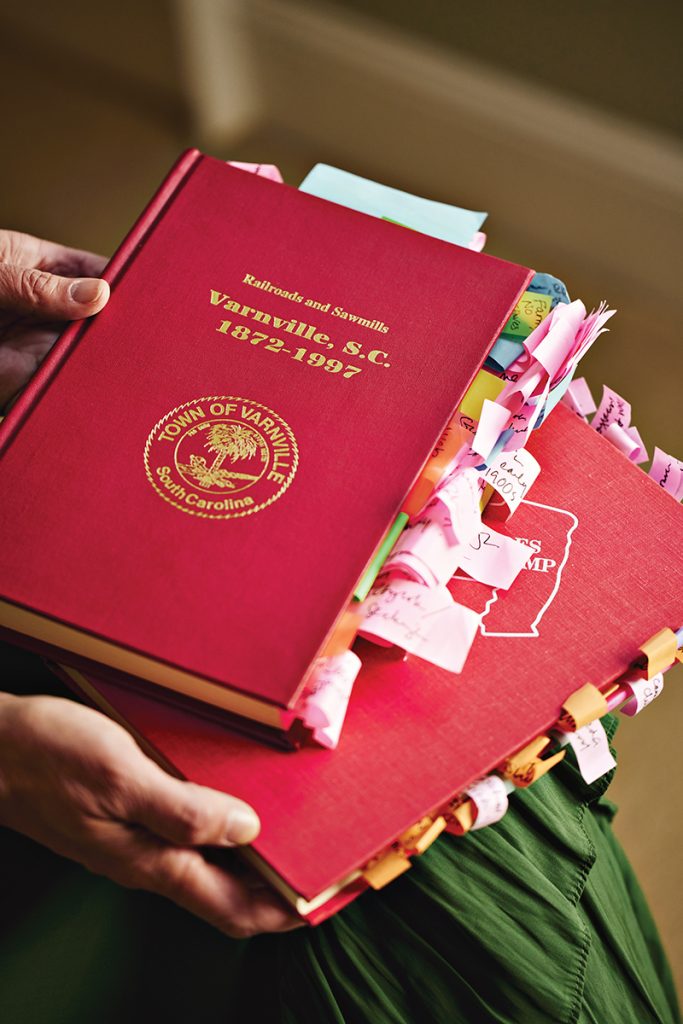

I spent nine months studying this family. There’s a library in Columbia that has all of the Hampton County Guardian archives; I went through them and tried to understand the history there. I interviewed a lot of historians.

The Deep South is different from North Carolina. It’s not that the Civil War skipped us here, but it took us a long time to get into it. That’s not the case in South Carolina. They’re the state that fired on the federal government. They’re the state that started the Civil War, that welcomed it.

When you are in a place of 20,000 people like Hampton County in S.C., where Sherman marched through in two flanks and burned everything — brought through 60,000 troops — it’s like being in Normandy. It’s like being in Dresden. It is a city, a place, that’s still haunted by this fundamental narrative of what happened there. Everybody lost everything. Everybody started from nothing again.

And they’re still mad about it.

You make it clear that not only the history but the topography of Hampton County, the soil and the setting, is inseparable from the story. You make a really interesting point about the economics of the infertile land and how it prohibits basically everything.

Everything! I spent months understanding the importance of the railroads there. I grew up understanding that kind of thing as a kid in Wilmington. When I grew up, Wilmington had something like 30,000 people. It was a tiny town. I bought my prom dress in Myrtle Beach, which was the closest big town. When I was at Duke, for the first two years it would take you better than three hours to get from Wilmington to Durham. Once I-40 got finished, everything changed. Wilmington became a different place. You just see the importance of transportation and how it changes systems. And so it was very clear to me that when the railroad came through Hampton County and they put down a station, well, it changed everything.

Of course a town builds up around every little station. And then the Murdaugh family and the Varn family that they married into had the most land. They donated land for the town, and that’s where the courthouse goes. And so once there’s a courthouse, then that’s where everybody from a hundred miles goes to court.

You did a really deep dive not only into the history but into the present day. You went and lived down there, you lived and breathed it for weeks on end. You entered this thick, ugly morass that had trapped and killed people. Were you scared for your safety? Were you scared for your mental health, for your emotional wellbeing?

Oh, for sure. Yeah. I was scared. I mean, I’ve been doing this a really long time. I’ve been a reporter 29 years, always out in the field. And I was a night cops reporter. The only other time in my life that I’ve been followed was 25 years ago, when I was writing a big exposé about a sheriff’s office that was deeply corrupt.

But I was followed a couple times on this story. So I ended up changing my approach. I would go places with someone else, somebody that was from there who could vouch for me, that understood what I was trying to do, that had gotten to know me and had some degree of trust.

The first time I went to Hampton County, I had not ever in my career been to a place that was so insular. Hampton is a town of 2,000 people and suddenly there were six reporters doing stand-ups outside the one cafe. They felt very much under siege.

Before I went down, I called every member of the county council. And so then I knew, oh, that’s Alex’s childhood friend, that’s [his wife] Maggie’s best friend from aerobics, that’s the son of the police chief. Every single person had multiple points of contact with the Murdaugh family. There were many, many reasons that it was hard for people to want to even engage with journalists.

Among the journalists there, you were widely considered to be the authority. You were the key on-camera source for the Netflix documentary. You were chosen by the press pool to be their representative to visit the scene of the crime, the Moselle property, a 1,770-acre family tract with hunting and fishing facilities. What was that like?

My editor in New York said, with great power comes great responsibility. Don’t screw this up. Moselle is so enormous. It’s two times as big as Central Park. But then the area where the murders took place is so small when you get there. The first thing I did was make a beeline for where Maggie stood, because the evidence specialist had told us how many steps she was from where Paul died. Where she was standing was 12 steps from where he died. I stood where she stood, and I burst into tears. I think that’s partly because we were close in age, and I have a son, and she has a son, and partly because she watched, she knew who killed him, and she watched who killed her.

There are thin places in this world, where the line between the living and the dead is very thin. And I think Moselle is one of them, very much a haunted place. There is much unfinished business out there.

I felt a sense of real obligation, but also real heaviness there. It was a challenge to me to accept that real evil exists in the world. And I think it found a home in Alex. And that was hard. That was hard to accept.

How would you describe the arc of Alex’s character in your story?

I wanted to think about Alex in the same way I thought about Paul, which is with some sympathy. But then one of his law partners said — I’ll never forget it — he said: I think Alex was stealing milk money in the lunch line from the time he was a little boy. And I think that’s probably true. There’s something in his wiring. So there’s the combination of something in his wiring being deeply off, and then never, ever being held accountable to anything. Ever. I mean, there are so many stories, lying about the fraternity fundraiser money when he was a KA at USC, or always cutting corners. He never got held accountable for one thing.

I talk to people who say: I loved him like a brother. I loved him. But I never really knew him.

I had held out hope I would get to interview him. That was my hope. And I had a line to the family, a close line to the lawyers. And then he gave us two days on the stand of who he was. And then again, in his sentencing, he poured his heart out, and it became clear to me that interviewing him would be a fool’s errand. He doesn’t know himself at all.

So I don’t know. We all have known people that are like a mirage. I think he is like a mirage.

Tell me about the epigraph, the Cormac McCarthy quote at the beginning of the book that is the source of the title. It seems to set up the idea that Alex was bad from the beginning, that he was made that way.

I wanted a title that telegraphed to readers that I was trying to tell a real story. That this is a saga. And so I went back to every book I loved for inspiration. Fatal Vision, The Sound and the Fury. Shakespeare. I re-read Macbeth. I read King Lear. I read the Old Testament. Anything that had to do with a father and a son.

And there’s just not an antecedent for what he did. There is not an antecedent for a parent killing an adult child. Abraham and Isaac don’t go through with it. Zeus and Kronos don’t go through with it. It’s so taboo. So I wasn’t finding what I needed.

Cormac McCarthy had recently died, and I love him. Blood Meridian was something I read in college. And so I was looking through it and I saw “When God made man the devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything.”

A church friend of mine said that it’s fascinating that inherent in the word devil is the word evil. And this is a story of deep evil, just deep evil.

This article originally appeared in the August 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.