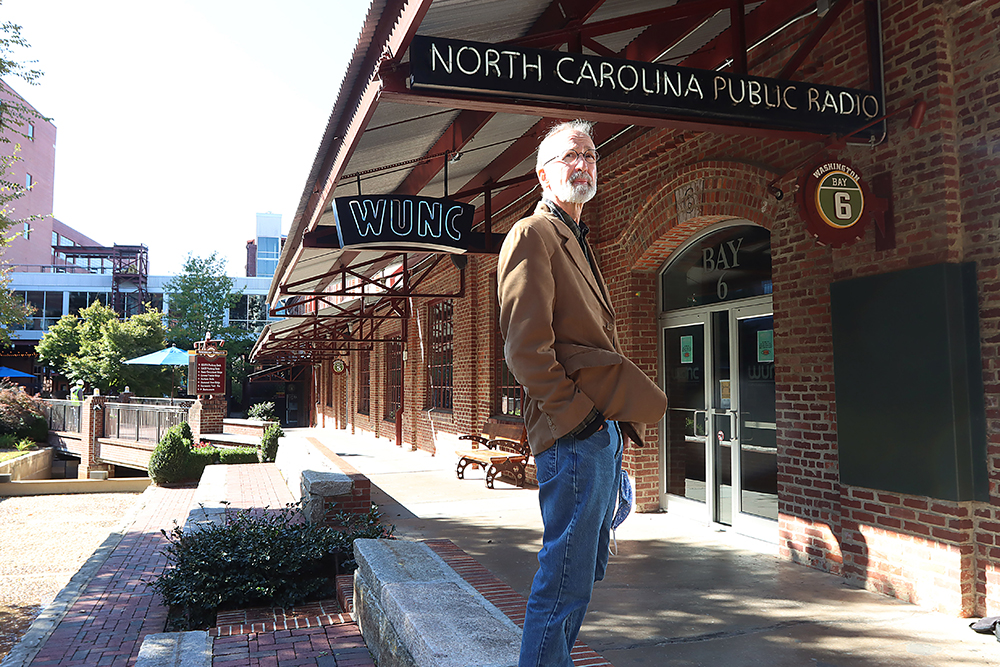

As WUNC’s popular radio show comes to an end, Frank Stasio shares stories about his path to public radio.

by Finn Cohen | photography by Bob Karp

For the last 14 years, Frank Stasio’s inviting timbre and inquisitive manner made WUNC’s The State of Things appointment listening. At noon nearly every weekday, Stasio has interviewed everyone from politicians and educators to artists, chefs, activists and scientists with the same genuine curiosity and warmth.

But this September, Stasio shocked listeners and colleagues alike when he announced that he’d be retiring. “Hosting The State of Things has been an illuminating and thrilling part of my journey,” he wrote in a note to the station’s staff. “The sudden rupture created by the pandemic makes this the perfect moment to follow the adventure in new directions.” A few weeks later, WUNC announced they would stop broadcasting the show.

Stasio has been a consistent examiner of North Carolina’s politics and culture. But as he put it recently, the tumultuous events of this year made him re-examine his work. The daily task of contextualizing a broad spectrum of issues for listeners simply became untenable amid what has been a difficult year for nearly everyone.

“My job is to frame a conversation, right?” Stasio says, a few weeks after his retirement announcement. “I find it difficult to put all of this in a frame because I don’t want to see it in a frame; I want to watch it billow and fractal—these immeasurable, unstandard pieces have no rational conclusion.”

Stasio, 67, had been cruising along for a few years, hosting the show four days a week (co-host Anita Rao covers the fifth) with the idea that he’d retire at 70, “a nice round number.” But by the middle of this year, he says, he didn’t feel right providing listeners with context when he was having trouble sorting through it all himself.

“I’m not burned out,” he says. “I feel like what I’m doing isn’t appropriate for me in this moment.”

Stasio has no immediate plans other than spending time with his four grandchildren in Durham. With them, he’s been sharing his first love: radio theater. Working with children should come easily, considering that Stasio took a six-year break from broadcasting in the middle of his career to help start a charter school in Washington, D.C. In fact, much of the professional path that led him to North Carolina has been a series of detours.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Stasio did some radio production in college and fell into internships at news departments for commercial stations. This led him to Iowa, and similar jobs that he was less than excited by. “That was pretty miserable,” he says. “I didn’t want to do news; it bores me.”

Eventually Stasio found his way to National Public Radio and moved his family to Washington, D.C., where he worked as a newscaster until that innate curiosity got the best of him. He had become fascinated with children’s education, and when he heard that the Capital Children’s Museum was starting a radio station in 1989, he knocked on the door, looking for a way to help out.

The museum was also starting a school, and the director asked Stasio if he would be interested in teaching a radio production class. With two young children, a full-time job at NPR and no teaching experience, Stasio initially balked. But when he thought deeper about it, his tune changed.

“If you’re listening to what is being asked of you in the big wide world, sometimes you just have to sort of answer that,” he says. He eventually quit NPR and took the teaching gig. “I was the only classroom teacher who was there both the day it opened and the day it closed.”

The school closed in 1996, and Stasio returned to public radio, filling in for newscasting gigs and talk show hosts, where he honed his interview skills. He traveled around the country doing radio theater workshops and to former Soviet states across Europe to help stations there learn about independent journalism. Then he started getting calls to pick up some talk show gigs at WUNC, which in the early 2000s was trying to build a slate of such programs.

“I started talking to people in North Carolina, and holy stuff,” he says. “I’d never been, including NPR, at a place where I could have this kind of deep conversation, really rich and meaningful conversations.”

“I always tell people I feel like I learned how to ask questions [from him],” says Mary Surya, Stasio’s daughter, who laughed recalling the first time she ever voted. She called her dad for some advice: “I asked him, What am I supposed to vote for? And he was like, Are you serious? I’m not going to tell you what to vote for — let’s talk about it. Let’s discuss it. And I was like, Ahhh! There’s no time!”

After a few years of traveling back and forth from D.C. to the Triangle, Stasio and his wife Joanne settled in Durham. As The State of Things became his full-time gig, North Carolina residents were gifted with an outsider’s fascinated perspective on their state.

“I had great confidence in collaborating with a host who knows how to get the best out of a conversation,” Thomas says. “One who listens deeply enough to be able to sustain whatever kind of length of time needs to be filled without feeling like they’re just trying to get to the end of the hour.”

That personal touch is something Stasio says he adheres to for guests, especially ones with whom he may have conflicting political or social beliefs. Stasio has come to see part of his job as being a conduit for listeners, providing them with snapshots of their community, not polarizing rhetoric. Every guest, he says, is more than just the frame they’re put in for his show.

“Don’t look at them as the role you’re asking them to play,” says Stasio. “It’s you who’s casting them in a role.”

That commitment to deep listening was apparent to Eleanor Spicer Rice, a Raleigh-based entomologist who has been on The State of Things twice. Her first appearance was also her very first radio interview, so she was pretty nervous. But Stasio spent some time with her before they went on the air, which made her feel at ease.

“He just sat down with me like he had all the time in the world, and within three minutes, the conversation went from ants to Buddhism to collective consciousness,” says Rice. “He has such a beautiful breadth of knowledge that he touched on in this tiny amount of time.”

Building connections through conversation is “a bit of theater that we do every day,” says Stasio. “And it should be; it should be theater in the highest and best sense.”