Before he owned his own studio and grew a cult following among local fitness fanatics, Jojo Polk and his family faced hardship.

Written by Lori D. R. Wiggins | photography by Gus Samarco

“Time doesn’t stand still,” Jojo Polk tells a group of about 15 sweaty, heavy-breathing CORE clients during a recent morning workout. The fitness instructor references a mantra he adopted from his high school football coach: D.I.G., short for Determination, Intensity, Guts. “You’ve got to fight for every second. Make it mean something to you. Dig! Dig! Dig! Diiiiiiiig! Don’t slow down now. Every. Second. Counts!” Polk, more than most people, knows that this is true.

At 22, long before he became the owner of CORE Fitness Studio on Capital Boulevard, Joseph “Jojo” Polk was in line to become an American football powerhouse. He’d graduated from Northeastern State University, a small Division II school in Oklahoma that caught the unusual attention of professional scouts. Polk, a cornerback from Lawrence, Kansas, was nicknamed “Lil’ Deion” after pro-football Hall of Famer Deion Sanders, for his prowess as a defensive back. His pro-combine performance made the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs take note. Waiting his turn, Polk joined the Tulsa Talons in the Arena Football League, an indoor, faster-paced sheepskin battle. The Chiefs signed him before his rookie season ended. With a few days before the Chief’s camp, Polk had one last matchup: Game 7, Talons v. Swamp Foxes of Charleston, South Carolina. A win would mean a Talons playoff bid.

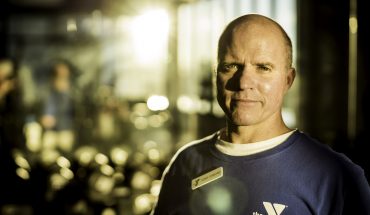

A photo of Polk from the Grand Rapids Rampage, this was taken the year after he broke his neck: the year he won the championship.

Seven plays into the game, “I was bating the quarterback,” says Polk. “I was going to pick it off and then take it to the house.” But Polk misstepped, tripped over a downed receiver and crashed head-first into the padded wall bordering the field. “I broke my C6 in half. My C5 was protruding into my C4, and C7 into my spine,” Polk says, detailing injuries to his vertebrae.

Translation: Jojo Polk was paralyzed from the waist down.

Doctors doubted he’d walk again. That was July 2000. Polk spent over two months at Tulane University Medical Center in New Orleans, where his mother lived. Battling disbelief and leg spasms that mimic movement, he leaned on his grandmother’s words: “Just pray about it.”

Pray he did—alongside months of grueling physical therapy, with his D.I.G. mantra on repeat—and little by little, Polk began to move his legs, then walk, then run. And, eventually, play ball. In April 2001, Polk joined the AF2’s Grand Rapids Rampage. By August, he was hoisting the team’s championship trophy overhead. Photographs prove it, he says. Polk played arena football for eight more years, winning the 2001 Most Inspirational Player of the Year award, and two American Indoor Football Association championships. “Wow,” he says. “That’s all I can say. There was no medical reason, of course. Just my belief in God.”

It wouldn’t be the last time Polk multiplied that mustard seed of faith that his grandmother taught him to embrace. And it wouldn’t be the last time his grandmother’s words gave him wisdom. “You were meant to impact lives,” she’d often tell him.

There was Hurricane Katrina in 2005, that forced Polk, along with his mother and sister, to relocate to Atlanta. It was there that Polk met his wife, Shirley, who was visiting from Raleigh, through a mutual friend. “Before I knew it, I was in love,” Polk says. “Everything happens for a reason.” He moved to North Carolina, and in 2009, the couple got married. Their then one-year-old daughter, Aubrey, took her first steps at their wedding reception.

In November 2017, the Polks welcomed a son. They named him after his daddy and called him “LJ,” short for “Lil’ Jojo.” But preparing to go home two days later, Shirley Polk’s condition suddenly changed and quickly worsened. Twice, she flatlined. The diagnosis was postpartum cardiomyopathy, or PPCM, a rare, unexplained form of heart failure that strikes between the last month of pregnancy and five months postpartum. With only three percent heart function left, Shirley Polk was transported to Duke University Medical Center for a heart transplant. “It was surreal,” Polk says. “One of our happiest times became one of our worst.”

“I didn’t know that kind of pain existed, until then. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t sleep. I didn’t want to miss a second,” says Polk. The only thing he could do was pray about it. He asked others to pray, too. And as miraculously as Polk walked again after his injury, Shirley Polk’s heart function returned—without a transplant. Life got good again. “Don’t tell me there is no God,” Polk says. “Don’t tell me God isn’t good. All prayers were answered.” The couple are now American Heart Association ambassadors.

Alongside faith, fitness is Polk’s path. He knew he’d tapped into his own physical fitness to aid his recovery after paralysis. “My bones were strong, my muscles were strong; all of that helps your body heal itself,” Polk says. “It put me in a different category.” He saw the benefits his teammates got from off-season workouts with him and put it into practice as a trainer. After a few years of teaching his first fitness classes and personal training sessions around Raleigh, he became a partner at CORE, then owner in 2016.

“This is the closest thing I’ll have to a team, ever again,” says Polk, referring to CORE’s staff of six other trainers who work with him. Day to day, he transfers the energy and philosophy he’s relied on to endure life’s challenges to his CORE clients as an instructor and personal trainer. “I love fitness. I love the workout process, challenging the body. Everybody has to have some physical capacity to face whatever life brings. We’re doing this for a reason,” he says. “It’s our opportunity to help people survive.”