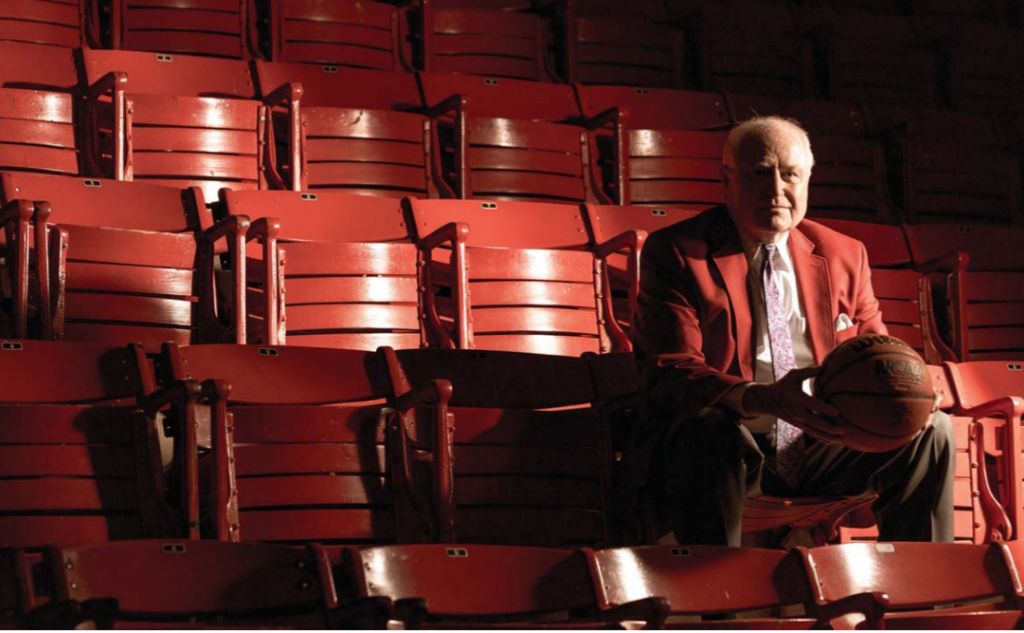

With faith and determination, this 5’9″ guard under Coach Everett Case made history.

by A.J. Carr | photography by Smith Hardy

Before Lou Pucillo arrived at North Carolina State University in 1956, Wolfpack fans had seen several championship teams, high-flying All-Americans, and electrifying uptempo basketball at its best.

But what the Reynolds Coliseum crowd hadn’t witnessed was anybody like Pucillo: a 5’9″, 150-pound guard — and the smallest player legendary coach Everett Case had ever awarded a scholarship. While not intentionally theatrical, Pucillo staged a scintillating show that included behind-the-back and between-the-legs dribbling and passing. His ballhandling was magical, his court vision 20-20, his performance highlight-reelworthy.

“He could pass the ball behind his back three quarters-length court and hit a guy cutting to the basket — Lou was very unique,” said NC State assistant Vic Bubas in a 1991 Raleigh Times column. Pucillo was the type of player fans loved and opponents loathed. In four short years, he became a “giant” in NC State basketball lore — and at age 84, Pucillo is still fondly remembered by oldtimers and revered throughout Wolfpack Nation. He’s an ACC Legend, and in the NCSU, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina Sports Halls of Fame.

Pretty remarkable for an athlete who never made the starting lineup on his high school basketball team.

The improbable journey to Raleigh began in Philadelphia, where Pucillo grew up with devoted parents and four siblings. “We had nothing fancy…but had a lot of love,” says Pucillo. He was raised in the Catholic church, sang in a youth choir, and attended Catholic schools for 12 years. He admired the dedication of the nuns who were his teachers, and believed what they told him in the ninth grade: if you do a novena — go to church nine straight days — you can wish for anything you want and you will get it.

“I had a very selfish reason for making this novena,” says Pucillo, reflecting on his decision as a high school freshman. “My wish was to play like [Boston Celtics ball-handling wizard] Bob Cousy and at a major college.”

For a long, agonizing time it appeared that wish would never come true. Pucillo was cut from the high school team his freshman and sophomore years, then was too “embarrassed” to go out as a junior and played in recreation leagues instead. He finally made the school squad as a senior, but didn’t crack the starting lineup.

Not that he hadn’t worked at the game. Pucillo played afternoons and nights, sometimes after shoveling snow off a dimly lit court. Walking home from the playground, he threw behind-the-back passes against the community row houses. “But I never broke a window!” he says. Before going to bed, Pucillo practiced dribbling in his basement, creating an incessant thump-thump that annoyed his next-door neighbor

“The saddest night of my athletic life was at my high school senior basketball banquet,” laments Pucillo, who thought his basketball days were over. “I felt I had failed, I felt betrayed [by the nuns], and that it was over.”

But Pucillo would get one more chance. His perceptive father, a Spanish teacher, encouraged him to attend Philadelphia’s Temple Prep after graduating from high school to take a language course, in case he wanted to go to college.

So Pucillo enrolled at Temple Prep to enhance his academic resume. When he found out the school had a basketball team, he tried out and made the squad. A year older and more experienced, this time he burgeoned into a star, leading his team in scoring and to a 24-1 record.

On how his basketball outlook turned from bleak to bright, Pucillo says: “I think it was divine intervention.”

It was at Temple Prep that he caught the eye of Vic Bubas during one of his less impressive performances. Playing against a deaf and mute team, Pucillo said, “I just went through the motions” in that game.

But Bubas, who later became a renowned recruiter and coach at Duke University, saw enough of Pucillo to notify NC State Coach Everett Case he had discovered a special 5’9″ prospect.

“Vic, have you been drinking?” asked Case, who preferred bigger, strong, gritty guards in the mold of State All-American Vic Molodet. Bubas was not only sober, but brazenly told Case he would have to change his way of coaching to maximize Pucillo’s razzle-dazzle style.

“Are you out of your mind?” replied Case, whose highly disciplined team was on track to win its ninth straight conference championship.

But Bubas persisted, and his resolve persuaded Case to award Pucillo the only scholarship he was offered. Case also gave a warning to Bubas: “You better be right.”

Bubas was right — and it appeared the nuns in Philadelphia were right, too. Over the next few years, Pucillo got his wish: he played big-time college basketball and was called a “Bob Cousy style” guard. Today, amid a gallery of pictures in his Raleigh home, is a prized photo of Pucillo and Cousy together at a Duke Children’s Classic.

Pucillo vexed opponents with bulldog tenacity on defense and offensive skills that included solid scoring to go along with countless assists, a stat that wasn’t kept in his era. He averaged 14.3 points as a junior and 15.4 as a senior, earned All-ACC honors twice, All-American one season, and was 1959 conference Athlete of the Year. That’s why his No. 20 glows among NC State’s honored jerseys.

“Lou took a dent from my playing time,’’ says Bucky Waters, a guard a year ahead of Pucillo at NC State who later coached at Duke. “He had a good shot and ball-handling skills. He was like a quarterback, had a great feel for the entire flow and knew where everybody was on the court.”

While Pucillo routinely unfurled spectacular passes that revved up Wolfpack fans, Waters says: “He was not a Globetrotter, not a showtime guard. It was about efficiency. He just wanted to beat you — beat you whatever it took.”

The Pucillo-sparked Pack teams won the 1958 Dixie Classic and soundly defeated rival North Carolina in the 1959 ACC Tournament at Reynolds Coliseum, then cut down the nets, a celebratory championship tradition Case had started in the 1940s. Pucillo scored 22 points in the finals, got the Tournament MVP trophy, and was happy he could help his beloved coach collect a 10th Conference tournament title with the Wolfpack.

“Coach Case was so disciplined on the court and so kind off the court,” says Pucillo, adding that he learned much more than basketball from his clever and visionary mentor. “He taught me a lot about life.”

After his playing career, Pucillo returned to NC State at Case’s request to coach the freshman team for three seasons. Afterwards, he embarked on a successful 38-year business career, working first for a Richmond, Virginia, beverage company and later operating his own company in Raleigh.

During that time Pucillo and Marcie, his wife of 59 years, raised three children: Lynn, Lou II, and Lauren. They now have three grandchildren: Catherine, Kennedy, and Jordan. Not surprisingly, basketball runs deep throughout the family.

Between 1978 and 1980, Lynn was a standout point guard nicknamed “Magic” at Ravenscroft School. Lou II starred at the same school and shares the singlegame scoring record (47 points) with former Duke sharpshooter and current pro Ryan Kelly.

Then along came the dribbling grandchildren: Catherine played during her

grade-school days in Wilmington. This year Kennedy contributed to St. David School’s A team’s march to a conference-championship and perfect record. And Jordan, a sixth grader, was top scorer on St. David’s B squad — all bright moments during this dark pandemic season.

In addition to enjoying his family, Pucillo has made a significant impact in the community and beyond. His benevolent spirit soared during a lunch long ago with teammate Ronnie Shavlik, a State All-American in the 1950s who died at age 49. “Louie, as much as we’ve gotten from NC State, Wake County, and North Carolina, we’ve got to give back,’’ Pucillo remembers Shavlik saying. Inspired by his teammate’s words that day, Pucillo has consistently supported community causes like the YMCA, Boys & Girls Club, The V Foundation, Rex Hospital Open, Duke Children’s Classic, and NC State’s Wolfpack Club, and chaired a committee for The Ronnie Shavlik Memorial scholarship.

Pucillo’s circle of friends reaches beyond NC State boundaries. He enjoyed an amiable relationship with UNC coaches Dean Smith and Bill Guthridge, and was especially close with colorful Wake Forest coach and raconteur Bones McKinney, whom he chauffeured to speaking engagements during the 1960s and 1970s. “Bones was like a godfather,’’ said Pucillo, who was entertained by the coach’s humorous stories.

These days, Pucillo remains active with workouts “four or five times” per week and golf on Tuesdays and Thursdays. (“I don’t keep score,’’ he says.)

And for the last 27 years Pucillo has also been on an enriching spiritual journey, participating in Bible studies that began with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and Bible Study Fellowship. He also worships at Hayes Barton United Methodist Church and carries the names of about 250 people in his wallet; he prays for each of them. “I’ve always had a strong faith in the Lord Jesus Christ,” he says. “I can’t believe how you can live without a strong faith.” With that faith, Pucillo soldiers on, enjoying retirement, giving back to the community — and fervently backing the Wolfpack. He has supported all the NC State coaches and teams, and has been especially thrilled to watch guards Monte Towe (5’7″), Spud Webb (5’7″), and Chris Corchiani (6’1″).

But he’s more than a fan. Pucillo has long treasured his friendships with Wolfpack players and will forever be grateful to Everett Case, who died from cancer in 1966 and is buried at Raleigh Memorial Park. Says Pucillo: “Every time I ride by that cemetery on Highway 70, I blow my horn and say: Thank you, Coach Case, for giving me the only scholarship I was ever offered.