by Tina Haver Currin

photographs by Lissa Gotwals

The Uber driver isn’t sure what to think about Dupont Circle, an industrial road west of the Amtrak station and not far from The Pit in downtown Raleigh, where a 6,500-square-foot studio is tucked away inside a nondescript building. Its exterior cinder blocks are painted beige, and the sidewalk is cracked and broken. Across the street, a barbed-wire fence secures a vacant lot filled with rusted-out trucks. Scrappy weeds threaten to swallow them.

“Are you sure this is where you’re going?” asks the driver.

There’s no sign on the building, but the sound of machinery clanking and grinding says this is it. Inside, a collection of intricate sculptures headed for the Duke Energy headquarters on Fayetteville Street is angled in a way that makes them look like giant paper airplanes. A 13-foot shimmering steel and glass structure for Research Triangle Park rises just beyond them, and next to it sits the mammoth glass kiln that helped make it. On the concrete floor, spots of bright blue recall past paint jobs.

There’s no need for a marker here. The distinctive spiraled trusses, iridized glass, and titan projects of polished steel can only belong to one artist: Matt McConnell.

A Charlotte native and graduate of the N.C. State College of Design with degrees in architecture and industrial design, McConnell, 43, has been building some of Raleigh’s most iconic sculptures since 2001. You may have seen his elaborate honeycomb chandelier in Cameron Village’s Tupelo Honey Cafe, his frosty “ice moons” on display in his Boylan Heights studio, or his undulating electric-blue forms on the side of Raleigh’s newest downtown apartment tower, SkyHouse. In the city center, it’s hard to travel more than a few blocks without finding something McConnell has made.

“Matt’s work is a great example of how Raleigh has developed a community that integrates art and design to enhance the city’s architecture,” says Glenn Dunn, an attorney who commissioned McConnell and collaborated with him to develop a piece of dazzling blue glasswork for the N.C. Bar Association last year. “The things he and his associates can do with glass, metal, and other materials are amazing.”

These days, McConnell also works on new ways to economize the process. After years of executing projects alone, McConnell has recently hired three new employees, and on a winter’s day, project manager Drew Stowell and fabricators Richard “Hemi” Rose, Seth Spainhour, Tim Mintern, and Hormis Kalarickal are clanking away: cutting, welding, and polishing the hundreds of elements that will eventually form a single sculpture.

McConnell moves around the room, introducing each co-worker with a clap on the shoulder, like a proud parent. They smile and offer handshakes in return, though workplace grime darkens each outstretched palm. McConnell speaks quickly and technically, and walks while he talks. He relies on scraps from previous projects to explain particularly technical concepts, like the geometric wooden templates he’s created to bend wire by hand into spirals of varying tightness.

Though they come from cubbies built into the walls and tucked beneath workbenches, he seems to materialize these remnants out of thin air, like a magician who knows each of his props by heart. It’s helpful to have a bank of templates and experience to reference, he explains. As his commissions get larger – figuratively and literally – McConnell’s challenge is to develop systems that couple his artistic vision with precise, mathematical planning. He’s become artist and entrepreneur, sculptor and architect.

Above and below: McConnell works on the design for a metal and glass sculpture for RTP headquarters.

“Of all the artists that I work with, I’m most comfortable working with Matt on spaces that I know are going to require more involved thought. He has an architectural way of thinking about things, but with a very artistic finesse,” says Heather Stewart, a curator for Kalisher, a hospitality art consultancy. Stewart has worked with McConnell on several projects, most notably Rhythm, a 10-by-14-foot sculpture with 166 cymbals for the Omni Hotel in Nashville, Tenn.

“Of all the artists that I work with, I’m most comfortable working with Matt on spaces that I know are going to require more involved thought. He has an architectural way of thinking about things, but with a very artistic finesse,” says Heather Stewart, a curator for Kalisher, a hospitality art consultancy. Stewart has worked with McConnell on several projects, most notably Rhythm, a 10-by-14-foot sculpture with 166 cymbals for the Omni Hotel in Nashville, Tenn.

“I know that if Matt is on board, we’re going to get to a really polished piece, which is important when you start getting bigger and more complicated projects,” Stewart says.

Meticulous approach

McConnell says he used a “mathematical system” to create the SkyHouse project, Rise, a 36-foot-long aluminum sculpture with a shimmering, catalyzed urethane finish. It has 13 shapes that repeat economically to create dramatic depth and movement.

“It’s flipped and turned back and forth, so that you get a helix,” McConnell explains, pointing out the CAD renderings on his computer with the enthusiastic gesticulations of a jolly professor. “A lot of what goes on here is creative problem-solving. We have to make money to keep us afloat, and the client has to find the money in their budget. So, how can we build in the most efficient way possible?”

That efficiency was critical for McConnell’s most recent sculpture, a giant undertaking that filled the studio with steel and sound throughout the month of December. McConnell and his team spent four weeks fabricating the 90-foot stretch of steel that now hangs from the ceiling of the 21st floor of Duke Energy’s downtown headquarters. At 6 feet wide and two-and-a-half feet tall, the sculpture’s silver lines create a visually striking, snake-like pattern that appears to shift when employees walk from one end of the building to the other.

McConnell cuts glass, layers it, and places it in a kiln to be melted together. The outer layers of iridized glass on the piece will shimmer when the sun hits it, while at night , it will be lit with color-changing LED systems.

“It was important for us to support someone locally who understood our company’s long history in the Triangle and North Carolina,” says Robert Veit, regional facilities asset manager for Duke Energy. “He’s open to feedback, so a design evolves and develops as it’s discussed. Matt was able to take ideas from the architect and us and incorporate them into his vision.”

McConnell estimates that the project, called Transmission, comprised 2,000 metal rods, each of which were cut and coped by hand (the team spent $2,000 on cutting blades alone). It took approximately 3,600 welds to fuse everything together.

“We do all this math to get to assembly, but a big part of the process is avoiding a situation where you have to move a part here, shim a piece there,” McConnell explains. “My brain creates the kind of shapes you see, but my brain is also breaking it down into a series of steps, and the best way to communicate those steps to the team.”

He walks over to a box of silver rods and the small mechanism that bends them into a loop. He holds one ring between his fingers, and then drops it into a box filled with countless others. It lands with a satisfying tink.

“Some days, it’s just make a ring, make a ring, make a ring. Each 24-foot section required 36 rings (for Transmission’s hanging apparatus), so we’re making all of them, flattening them all out. That, after cutting 2,000 pieces of rod. It can be fairly maddening,” he says, chuckling. “But I like having 500 little parts and lining them all up and taking a picture. Documenting the process reminds me that there is beauty in the doing.”

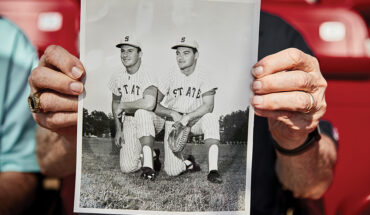

‘Humble’ beginnings

McConnell’s first paying gig happened by accident in 1999. He was setting up a show of his sculpture organized by the (now-defunct) downtown art gallery Forum+Function at the (still-thriving) tapas restaurant Humble Pie. McConnell wasn’t satisfied with the space’s lighting, so he asked if he could bring some lights he’d made to install over the bar. The golden, orb-like fixtures received so many compliments that when the rest of the show packed up and moved on, the lights stayed behind (they’re still hanging there).

The Humble Pie lighting led to two more jobs. First, McConnell was commissioned to create a smaller version of the orbs for a fan’s dining room. Then, as he stacked them for delivery, the new assembly struck the artist as significant. He created a version of the light-stack in Photoshop and sent it to the North Carolina Museum of Art, which bought the piece in July of 2001. Now known as Stratus, the work is part of the museum’s permanent collection and hangs near the Special Exhibition Café in the East Building.

But it’s not all happy accidents, or purely creative pursuits, in the studio. As a public, commercial, and residential artist, McConnell often spends months on proposals, intricate 3-D computer animations, meetings, and design changes before he even begins to assemble a team or build a sculpture.

“It’s really a testament to his creativity,” says Kalisher’s Heather Stewart, “because we come to him with all of these constraints and say, ‘Here’s your money, here are the things we want to accomplish, here are some themes.’ When you give him all those little caveats, like the client really hates orange and it’s got to incorporate vertical lines, Matt always comes through, and you know it’s going to be just beautiful when he’s done.”

Two of McConnell’s sculptures in the Duke Energy building: Transmission (above) sits on the building’s top floor above an indoor walking track for employees. Arc (below) stands in a walkway.

McConnell says it all comes down to planning, dialogue, and trust, which lead to successful collaboration during the design process. He cites the Lincoln Apartments, one block east of Moore Square, as a valuable partnership that resulted in both a handsome sculpture and a happy client. He created two pieces – one indoor, one outdoor – for the complex in 2015.

The interior Lincoln piece, Pitch, is a pair of fiery-red pieces of twisted steel that look like little wisps of flame from a candlewick. Outside, a collection of four square and four rectangular sculptures ornament the massive parking deck. The wavy beams recall topographic maps, and if you look closely, you’ll notice a blue shimmer in the paint – a nod to its cousin a few blocks away on SkyHouse.

“People are going to drive by and see their sculpture, and they’re either going to go ‘Huh?’ or ‘Wow!’ And we want ‘Wow.’”

But it was Transmission, the immense project for Duke Energy the team installed in December of 2015, that gave McConnell the freedom to think big, and has given him a deep sense of satisfaction as an artist and a businessperson.

Now he just has to decide what he wants to do next.

“The Duke project was really an affirmation for me, to work through an idea without having to cap it,” McConnell says. Recently, he says, he has become inspired to “make something just for me, something that I put in a closet somewhere.” Because his public work is meant to reflect the client and please the public, by definition it’s not for him. It has to do a job. “I am always taking a picture and sharing every little detail.” But “work that nobody sees,” he says, “could be pure.”

He pauses to look around his studio, and then begins to laugh. “As soon as I find something that pure, I will want to make a big one. I’ll be out there meeting people and saying, what about this?”