…on lentils, death, and the joy of befriending strangers.

by Addie Ladner

People who experience cultural immersion might reference a language course or a semester abroad. For me, it came by way of the life and eventual death of a neighbor, a second-generation Greek immigrant, Larry Marangos. Come March, Larry would have been 79. Honest and fascinated by history, “you’re not listening to me right now,” he said once while going into great detail about the real story of the PBS Masterpiece Classic Durrells in Corfu. I was making sure a child didn’t dart into the street.

He was an enigma, wanting to live to 90, yet smoked and rarely left his house. “Don’t Greeks live an active lifestyle?” I’d ask. Born and raised in Raleigh and baptized in the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church here, his name is still visibly handwritten in Greek on page seven of the church’s first baptismal ledger from 1942.

As a studious young boy, Larry would cross the now bumper-to-bumper Hillsborough Street walking to Fred Olds Elementary. He knew everything about everyone, though you rarely saw him. A brilliant professor earlier in his life, he spoke fluent French, Latin, Greek, and Spanish (to which he would begrudgingly translate for me).

He lived in the same home he grew up in on Stanhope Avenue, which did not appear to have changed at all, filled with prints of Marylin Monroe, old records, and worldly artifacts. Living across the street from him, through osmosis and intrigue, I adopted a handful of things from the Greeks.

For instance: only buy sheep’s milk feta, a big block, in the brine. And: the best way to serve lentils is a bit undercooked, with rice, parsley, olive oil, and lemon. (“These aren’t the lentils I grew up eating,” he said, after trying a hearty lentil tomato soup I’d made.)

And: one should not keep too busy. Each year, he’d clip out admission coupons to the church’s annual Greek Fest and leave them on our front porch. But he had no interest in attending such hoopla. “No,” he’d say, “you need to learn to say no yourself sometimes.” He wasn’t wrong. It took three years of persistent invites — and the birth of my first child — for him to join us.

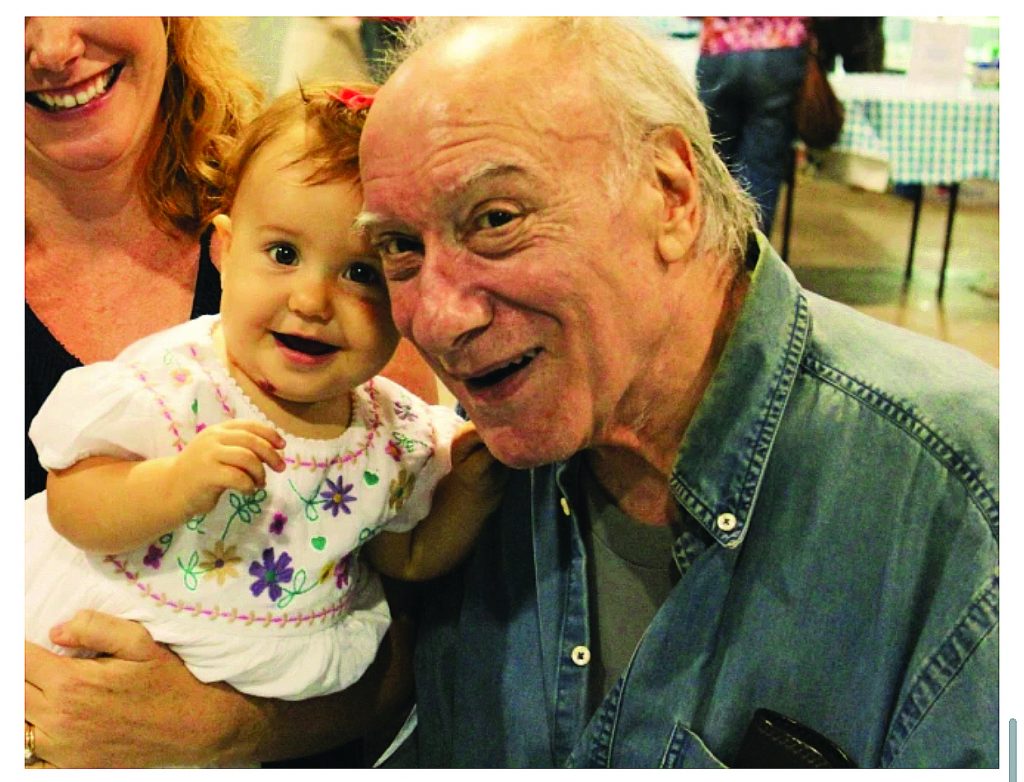

They were connected. “Isn’t that the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen?” he said at their first meeting. The most positive thing I’d heard come out of his ornery mouth, again he wasn’t wrong. With a buttery new baby to show off, he happily joined. At Greek Fest, he went from an orney neighbor to a social butterfly.

While I never quite understood Larry, one thing was for certain, his faith. “Larry wasn’t afraid of death,” the priest said at his eulogy. It gave me chills to hear, knowing how true it was. He’d always leave N&O clippings in my mailbox, often of an obituary of a friend. Out of habit, I’d respond, “Oh I’m sorry, how sad.” “Why are you afraid of death? I’m not,” he’d say. He wasn’t.

Once, I found him on the floor of his house; he’d been there for three days. I called 911, and as I frantically answered questions from the paramedic about his cognitive state, I remember saying, “Well, now he’s smoking a cigarette — wait, Larry, why are you smoking a cigarette?!”

Very close to the end of his life, barely lucid, he asked me to read him his obituary, which he’d penned himself for The News & Observer.

After a long funeral service and burial in the Greek section of Historic Oakwood Cemetery, right next to his parents, my husband and I attended our first Makaria. Makaria, which translates to blessed, is the meal shared after a Greek funeral. Tucked into a corner of Casa Carbone Carbone on Glenwood Avenue, an Italian Restaurant that’s been around since the 1950s, we passed around a humble plate of lightly seared fish, a symbol of Christianity, then ceremoniously dipped biscotti into red wine, symbolizing the body and blood of Christ.

All the while, we talked about Larry, who started as a neighbor, then became a friend, then family.

At that dinner, I learned one final thing from Larry that would sum up our entire, ethereal relationship: philoxenia. A quintessential Greek trait, it means to be hospitable. To be kind and to love a stranger. Shouldn’t we all?