Catching up with a former Wake Forest basketball star who’s now a sports commentator and basketball analyst on the ACC Network.

by A.J. Carr | photography by Ben McKeown

As an expert basketball analyst on the ACC Network, Randolph Childress talks a lot about a plethora of elite players.

Years ago basketball analysts were talking a lot, often raving, about Childress, especially when he produced perhaps the most scintillating show in Atlantic Coast Conference Tournament history.

A 6-foot 2-inch guard with nifty moves and sharpshooter accuracy, Childress scored a tourney record 107 points in three games while leading Wake Forest University to the 1995 championship. If anybody exceeds his heroics at this month’s tournament in Washington, D.C., it’ll take a gallant effort, lights-out shooting — and maybe more. Rewind back to that 1995 classic in the Greensboro Coliseum.

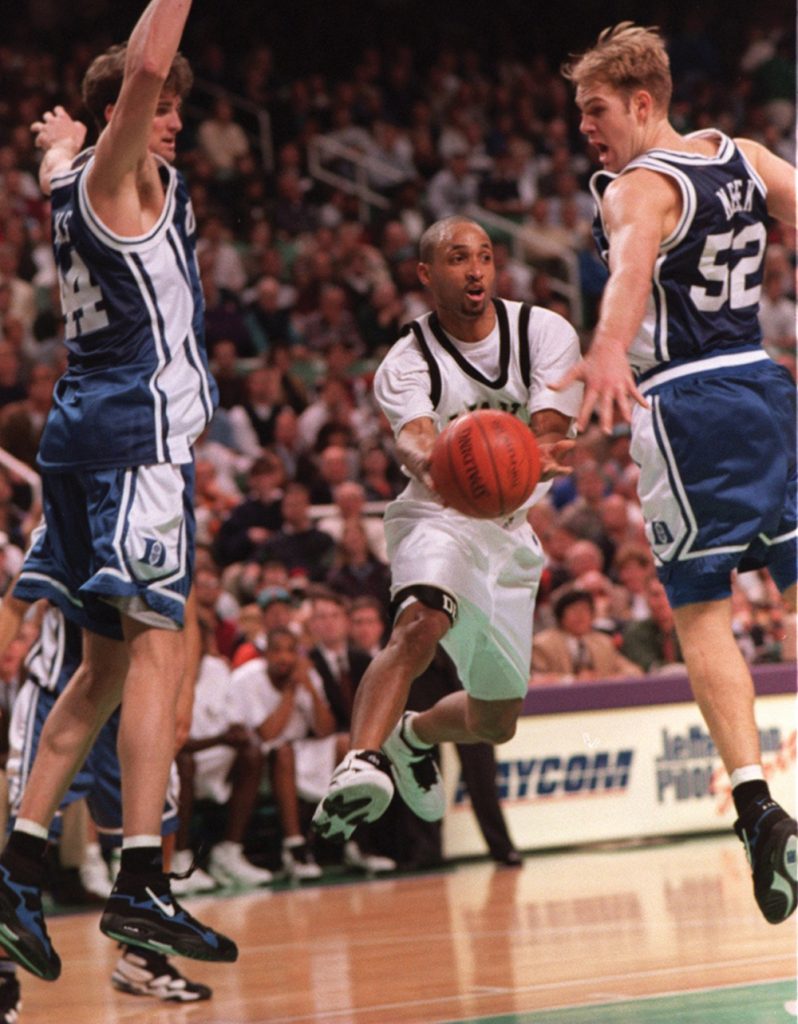

In the opening-round game the top-seeded Deacons started slowly, shot poorly and fell behind No. 10 seed Duke University by 18 points. During a time-out, Coach Dave Odom launched into his own March madness — some animated talk — when he was suddenly interrupted.

“Coach! Coach! That’s enough! Enough! Give it to me. We’ll be OK,” were the words Odom remembers hearing from Childress, a senior leader.

After that, as Odom aptly puts it, Childress took over the game and the tournament. The dazzling Deacon scored 40 points, made 10 straight shots in one stretch and led Wake to an 87-70 comeback win over the Blue Devils.

“That was the best game I ever played,” says Childress, who seemed impervious to the pressure and teeming tournament atmosphere.

The Deacons went on to claim the championship by beating University of Virginia in the semifinals and highly ranked University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in a dramatic overtime title game.

Childress’ star never flickered. He tallied 30 points against UVA and 37 points versus UNC — including all nine Wake points and the game-winning shot with four seconds remaining in overtime. His 107 total points broke the tournament record of 106 set by North Carolina legend Lennie Rosenbluth in the 1950s.

While getting some help from team mates, notably All-American Tim Duncan, it was the undaunted, determined Childress who rose above the crowd in the moments that mattered most, saved Wake, and earned MVP honors.

He did all that after having struggled with an injured left shoulder that kept popping in and out

of joint, preventing him from practicing the entire week leading into the tournament. Childress wrestled for days with a “feeling of desperation.” But once in Greensboro, he says: “My adrenalin pumped up, I just played, and the rest is history.”

Childress carried extra incentive into that game with rival UNC after reading a quote attributed to one of the Tar Heels’ players. “I saw a clipping that said we would choke if the game was close. I circled that on my calendar,” says Childress.

How did Childress respond? He drove, swished a floater and Wake had an 82-80 victory and the championship trophy. “I don’t think I choked then,” quips Childress, a take-charge guard with gimme- me-the-ball confidence. “I might miss a shot, but I never choked.”

“He has never been afraid of any- thing,’’ Odom says. “He’s never faced an obstacle too big. He was clearly the leader from that standpoint. He was always the one person, the catalyst, to put us in the right direction. It was like ‘Lean On Me,’ the song – we’ll find a way.”

“I’ve always been confident and not afraid to fail. I live by that,” says Childress, confessing t hat he has experienced failures including painful basketball defeats.

While remembered most for his spectacular tournament performance, Childress wasn’t just a three-day wonder. After missing one season with an injury, he became the productive player Wake was expecting.

He recorded double-figure scoring for four seasons, finishing with an 18.4 career average and 2,208 points, second most all-time at Wake behind famous Deacon Dickie Hemric (2,587). He dished out assists. He played gritty defense, often guarding the opponents’ best players.

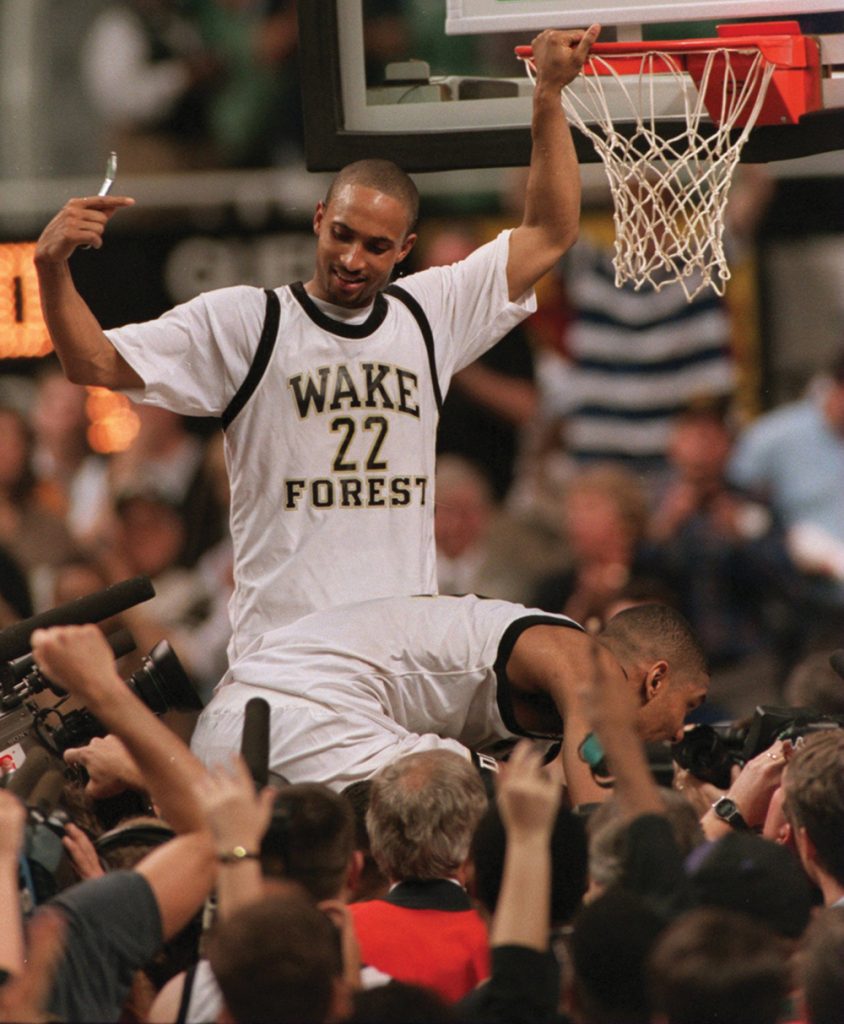

Childress’ resume resonates loudly: two-time All-America, three-time All-Conference, ACC Legend, jersey No. 22 retired, Deacons’ career three-point field goal leader, Wake Hall of Fame, North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame.

More than the individual accolades, Childress treasures winning the ACC championship. It was Wake Forest’s first conference tournament crown since 1962 and first of two straight titles under Odom’s strong leadership. Winning was what Childress had in mind when he committed to Wake after considering Maryland, Georgetown, North Carolina and Seton Hall. To get there, he traveled a circuitous route from his home in the D.C. area, playing at three different high schools, the last at Flint Hill in Oakton, Virginia.

“I struggled academically in school for two years,” Childress says. “When I went to Flint Hill it was a big thing for me. I got individual attention.” Why did he choose Wake?

“I had met [future NBA player] Rod- ney Rogers at a Nike Camp. He was a heck of a player and had committed to Wake,” says Childress, who wanted to join players who could not only win, but win championships.

When Childress signed, Odom, who coached Wake to some of its best basket- ball days, knew he had landed another prize recruit with a champion’s mentality and the talent to match. Childress says he chose the “right school” and played for the “right coach.”

“Coach Odom saw something in me,” Childress says. “He saw how I was and never tried to change that. He didn’t put me in a box, gave me full autonomy. He encouraged me. I give credit to him. He was the right coach for me.”

As the old saying goes, “if you have a great player, let him play great.” After graduating from Wake Forest with a degree in communication, Childress, a first-round draft choice, embarked on a 16-year pro career that included three seasons in the NBA and 13 overseas. Later, he spent nine years as an assistant at Wake, where he coached his son Brandon, who scored 1,415 career points.

Like some other former coaches and players, Childress moved from the bench to the broadcast booth in 2021, working with the ACC Network. He was an ad- mitted “trash talker” on the court during an era where chatter was permitted. Now he talks a good game, a smart game, providing insightful commentary for the television audience.

The TV work is a seasonal job and Childress, a man of faith and love for family, likes his flexible schedule. For one big thing, it gives him more time to con- nect with his four children — Brandon, Deven, Temeka and Kayla — and wife Tabetha. They’re based in Kernersville.

“I’m fortunate to call ACC games… I enjoy the high-level games,” he says, cognizant that the game has changed in some ways since he played. “Sche- matically teams are more three-point oriented, floor spacing is better, and it’s playing outside-in. But not everybody has changed so much. It’s still shooting, rebounding, who controls the paint, defending, not turning the ball over.”

Childress continued: “Basketball is so great. It has taken me around the world. The aches and pains have been worth every bit of it. I’m indebted to what the game gave me and I gave it all I had. I’m forever grateful.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.