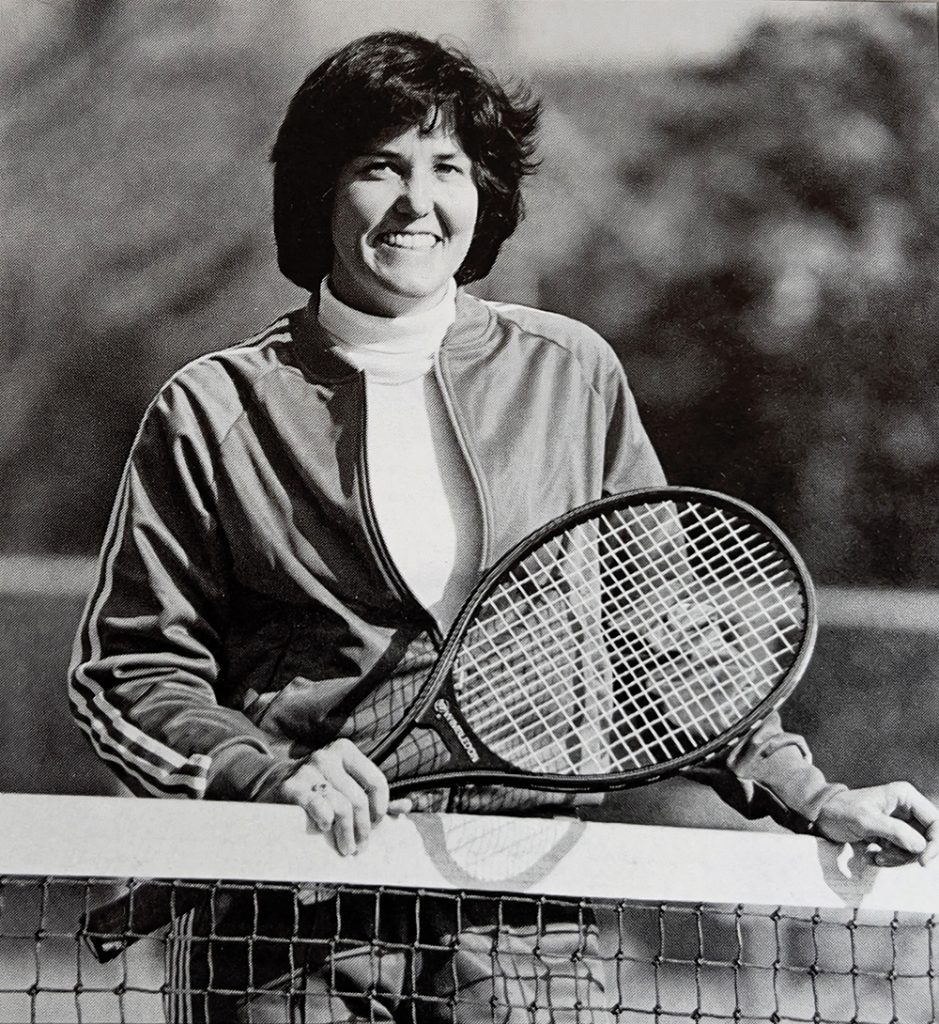

As a player and coach, Jane Preyer completed her Hall-of-Fame tennis career in 1991, but she’s never stopped serving

by AJ Carr

Not long after the last match, she started pouring her energy into nonprofit endeavors. That competitive fervor she displayed on the court and spirit of generosity in the community could be traced back to her home, where faith, service and tennis were prioritized.

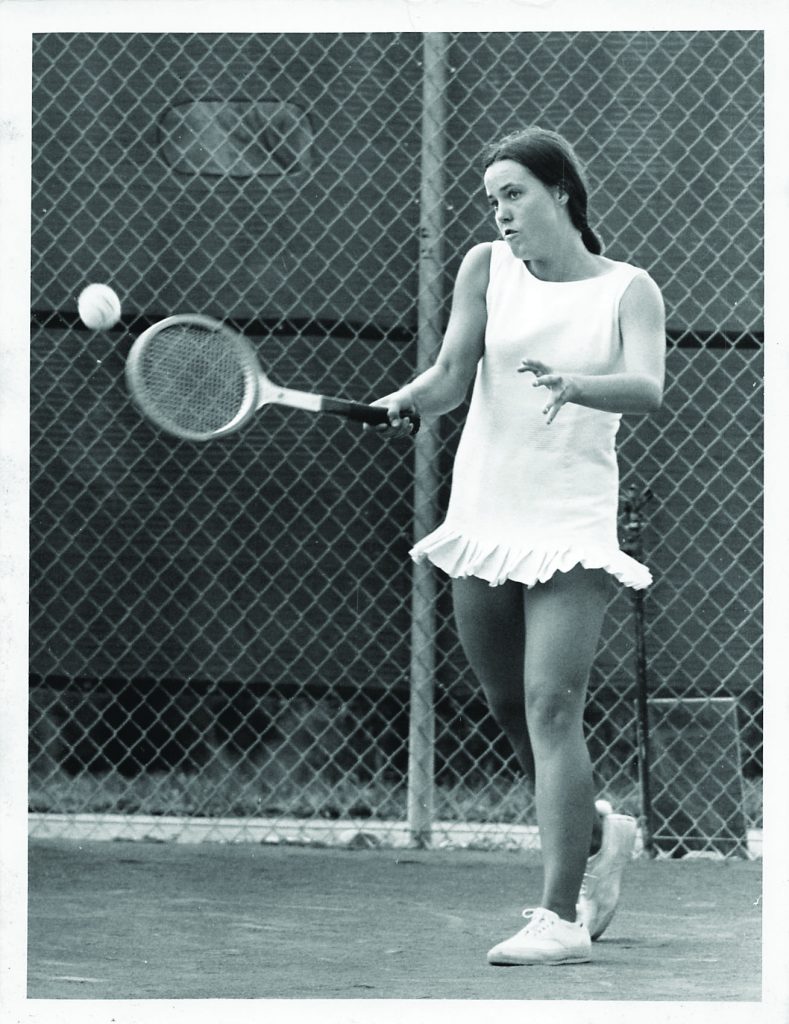

When Preyer wasn’t much taller than a wooden racquet, her mother Emily Harris Preyer made sure she and four siblings were on Greensboro’s public park courts and at First Presbyterian Church on Sundays. It was those early lessons from her mother and later training from teaching pro Dean Mathias that helped propel Preyer on her skyward tennis trajectory.

“I got her late, and she was already good,” said Mathias, a former Wake Forest and Atlantic Coast Conference doubles champion. “She just needed confidence, a little direction and condition.”

But Preyer wasn’t always totally absorbed with tennis. When her father, Richardson Preyer, was appointed U.S. District Judge by President John F. Kennedy, the family moved to the Washington, D.C., area and she attended Chatham Hall in Virginia. There, she was a four-sport athlete competing in basketball, field hockey, and lacrosse as well.

“I had a great time in team sports. It helped build my confidence. I think it’s great to have variety,” Preyer says, advocating for more young athletes today to compete in multiple sports.

It wasn’t until after playing basketball and tennis her freshman year at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that she refocused solely on her first love. (Tennis was, after all, the ticket to a pro circuit packed with stars like Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova.) At UNC, Preyer won four state junior titles — three doubles, one single. She earned All-America honors and was team captain, and she was also a Phi Beta Kappa student.

After college, she turned pro and gained a No. 42 world ranking over six years. Preyer traveled alone on the tour, boldly competing in all the Grand Slams and smaller tournaments around the world. It was both an arduous and gratifying odyssey.

Highlights included wins over four Top Ten-ranked opponents, reaching the round of 16 at Wimbledon and pushing iconic Billie Jean King to three sets before losing in the Australian Open. But her “finest hour” she says, unfolded in Perth, Australia, where Preyer upset her sports “idol” — 14-time Grand Slam champion Evonne Goolagong — in front of a raucous Aussie crowd.

The night before what most thought would be a mismatch, Preyer, then 104th in the world, remembers phoning her mentor, Mathias. She shook him out of deep sleep at 3 a.m. U.S. time with a question: How do I beat Evonne Goolagong?

“Do not hit to her backhand. Keep hitting to her forehand and go to the net. Attack all the time,” Mathias advised.

With a solid serve, judiciously placed approach shots and crisp volleys, Preyer implemented the Mathias game plan and won 6-3, 6-3 over one of her heros. Among her exuberant followers, none were more euphoric than her mother, who posted a giant sign in the front yard that read: Ding…Dong! Ding…Dong! Jane beat Goolagong!

“That was so embarrassing, but it was funny if you knew my mother,” Preyer says.

There were other celebratory moments, such as when she and her mother teamed up and earned second place in a national mother-daughter tournament. The runner-up trophy — a silver tennis ball — sits on Preyer’s office desk today.

Highs and lows were part of the tennis journey. Losing to Barbara Potter in the fourth round at Wimbledon “still haunts me,” Preyer says. A loss to precocious 14-year-old Tracy Austin was another stinging setback. But whatever the outcome, Preyer maintained equanimity — humble in victory, gracious in defeat.

“Jane is the epitome of sportsmanship and character,” said USTA official Debbie Southern, quoted in a Southern Tennis press release. “She never put winning over integrity. Other players on the tour felt the same way. I can also attest to the sportsmanship and character she instilled in her Duke teams as I coached against her.”

In 1993, her pro career was short-circuited by an elbow injury. Unable to play, Preyer quickly transitioned into coaching and guided Greensboro Page High to a state title in her only year directing the team. Then, much to the chagrin of UNC fans, she moved on to Duke University.

Going from Carolina stardom to rescue the Tar Heels’ biggest rival was tough. “I got a lot of grief for that — from both sides,” says Preyer. But she was resolute in transforming the Duke program to championship status. With scholarship support from then-Athletic Director Tom Butters, she recruited better players, created spirited team unity, coached with expertise, dominated the Atlantic Coast Conference and beat Carolina in every head-to-head match. She built a powerhouse women’s tennis program, going on to win four conference championships, four Coach of the Year awards and posting a 120-45 record in six seasons.

Her coaching, and particularly recruiting success, didn’t surprise Mathias.

“She has a great personality, is so charming to everybody,” he says. “I can’t think of anybody not wanting to play for her.”

Today she stands tall in three halls of fame: North Carolina, Southern Tennis and the Guilford County HOF. Preyer also received the esteemed USTA and Intercollegiate Tennis Association Community Service Award presented by former champions Arthur Ashe and Stan Smith during the 1990 U.S. Open.

While enjoying coaching, Preyer made the change in 1992 to a long, impactful career with nonprofits. As southeast director of the Environmental Defense Fund, she was instrumental in getting much-needed laws passed on pollution reduction, renewable energy and preferable paper usage. As a volunteer in health care, she saw how desperately families needed insurance and was passionate about getting coverage for them.

Over time, she served on boards for the North Carolina Center for Nonprofits, Children’s Home Society of North Carolina, and UNC-Chapel Hill Institute for the Arts & Humanities.

In 2005, Preyer, along with siblings, started the Emily Harris Preyer Family Endownment at the North Carolina Tennis Foundation in honor of their mother. The nonprofit provides educational and sports opportunities for youth needing financial support.

Today Preyer still avidly watches tennis, plays a little golf and likes to go hiking. She stays busy with board positions on the National Health Law Program, EarthShare NC and Environmental Defense Fund, and she worships at First Presbyterian Church in Chapel Hill. Still active and still serving at age 71.

This article originally appeared in the September 2025 issue of WALTER magazine.