Inside the North Carolina Museum of History, modest artifacts speak to the resilience of Black Athletes in America.

by Hampton Williams Hofer

On the third floor of the North Carolina Museum of History is an exhibit with a winding, burnt orange path, painted with white lanes like a track, jerseys hanging overhead. You can almost hear the echo of cheers as you follow the track past cases where lights shine on game-winning balls and trophies once hoisted by sweaty hands.

This is the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame, the permanent home to some 200 relics of Old North State sports heroes and their feats. Alongside the glass cases are champion driver Richard Petty’s stock car, an interactive monitor to test your sports trivia, and a scene of life-size replicas of basketball players — airborne in front of a screen that replays some of the best moments from monumental games.

Founded nearly 60 years ago, the Sports Hall of Fame inducts several new members each spring. Its home at the museum is a sea of familiar logos — wolves, heels, deacons, devils, and panthers — as well as household names like Michael Jordan and Julius Peppers. Hanging in the hall are Mike Krzyzewski’s Duke University warm-up jacket and Roy Williams’ signed #7 jersey. And while basketball is king around here, the Hall of Fame pays homage to everything from billiards to hang gliding, recognizing the greats from all areas of sport, including journalism and medicine.

Beyond the glitz of the trophies and the glamour of the big names, there are two quieter stars: a simple white cap, emblazoned with “USA” above its navy blue bill, and a plain gray uniform with coordinating tie-up cleats. The cap shaded George Williams’ face as he coached more than 40 track and field Olympians, three of them to gold. The uniform is what Walter “Buck” Leonard buttoned up before each game he played as one of the most talented clutch hitters in Negro League baseball. These relics tell a story that is bigger than record-breaking stats and prime-time sponsorship deals — the stories of people who surmounted incredible obstacles to lay the foundation for many other North Carolina athletes.

George Williams was the head coach of the USA Olympic track and field team in Athens, Greece, in 2004. He had built a powerhouse track and field program at his alma mater, Raleigh’s own Saint Augustine’s University. During his four-decade run as head coach, his men’s and women’s teams secured an astounding 39 NCAA Division II National Championships, and an almost unbelievable 282 individual national crowns. George Williams ranks third for the most championships in NCAA history, regardless of division, putting him well ahead of Nick Saban and Bobby Knight.

“You will never meet a more humble person than George,” says N.C. Sports HOF Director Bobby Guthrie. “When I was the athletic director for Wake County Schools, George always welcomed First in Fitness activities for our elementary and middle school students at Saint Aug’s. He has been around the world, is known around the world for his track expertise — but he will never talk about himself.” Three-time winner of The Order of the Long Leaf Pine Award — the highest civilian honor presented by thegGovernor of North Carolina — Williams was inducted into the N.C. Sports HOF in 2000.

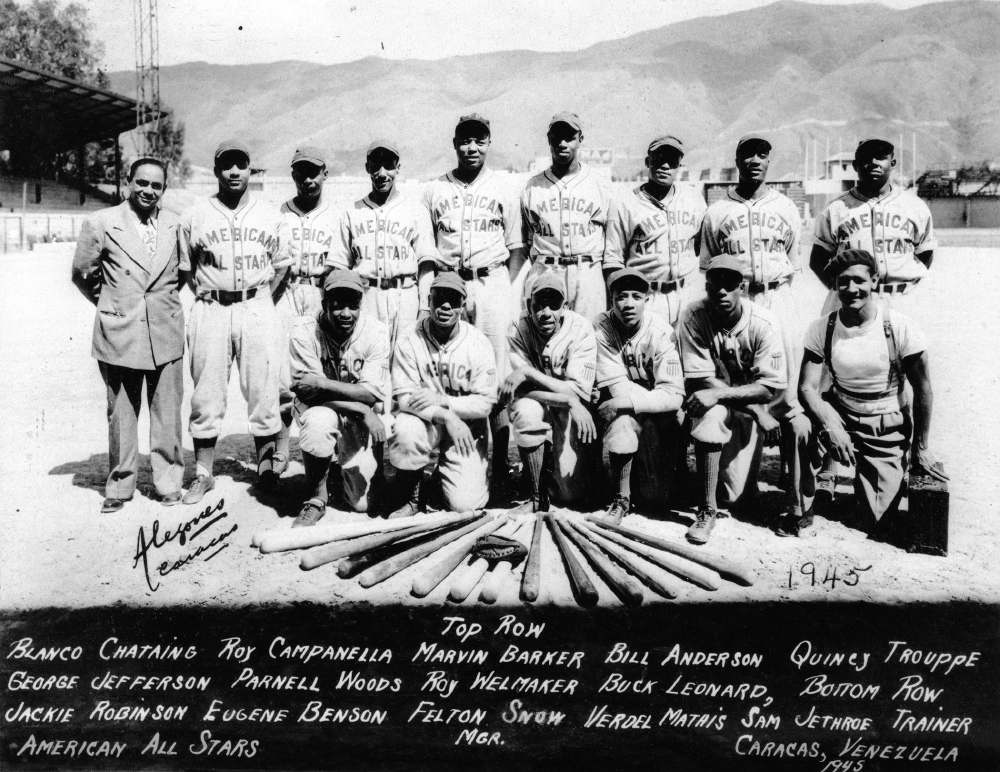

Not far from George Williams’ hat, behind another glass case at the history museum, sits the uniform of baseball great Walter “Buck” Leonard: simple, gray polyester button-up shirt, emblazoned with the team name “HOMESTEAD” and matching pants. The Wilson tag on the shirt still reads number “44” with instructions to machine wash only. Tall navy knee socks with worn cotton loops hang above plain black, lace-up baseball shoes. Buck Leonard led the Homestead (Pennsylvania) Grays to nine consecutive pennants from 1937 to 1945. He was the Negro League’s all-star first baseman an incredible 12 times.

As a little boy growing up in Rocky Mount, Leonard would sneak over to the baseball field of the local white team and watch through the fence as they pitched and hit. He was once arrested peeking through that fence, but he never lost his obsession with the game. With no Black high school in Rocky Mount, Leonard went to work for the rail station after eighth grade, eventually playing semi professional baseball on the side. His contemporary, Dave Barnhill, once said of Leonard: “You could put a fastball in a shotgun and you couldn’t shoot it by him.” Leonard worked his way to the Grays, widely considered one of the best teams in Negro League history.

“One of the highlights of the whole exhibit is the baseball uniform worn by Buck Leonard,” says Katie Edwards, the museum’s curator of popular culture. “He was a star first baseman during a time where African Americans were not allowed to play in the majors. He was so good, in fact, that he was the first North Carolinian inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.” Leonard, like George Williams, helped break the barriers for later Black Hall of Famers like Charlotte Smith, Andrea Stinson, Michael Jordan, and Julius Peppers.

Next to Leonard’s baseball uniform is a ball, dirty and worn, reminiscent of something from The Sandlot, with “Buck Leonard” written in careful cursive. There is nostalgia in the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame, and there is also pride. “Having a history like this can only help our youth to reach for their dreams,” says Guthrie. “We not only have a history of Hall of Famers in this state, we have a history of the best of the best.”

_____

This article originally appeared in the January 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine