Traveling with his father on a junket to meet the governor and vice president, a young man makes a detour

By Bland Simpson

On the last Saturday in March 1963, my father came and collected me in Chapel Hill, and we headed east on narrow, lonely NC 54 to go to Raleigh and get into politics. Just a few hundred yards shy of Nelson (then no more than a solitary filling station), we stopped to help a woman standing alone beside her car on the road shoulder — she had a flat tire and stood there desultorily making no move toward changing it.

Nor did I, but my father did.

I stayed in his car, a big Buick LeSabre, as he got out and walked slowly back to her, waving, smiling (I watched out the back window), and then bending to the task, which seemed interminable, the getting out of the lug wrench, the jack, the spare.

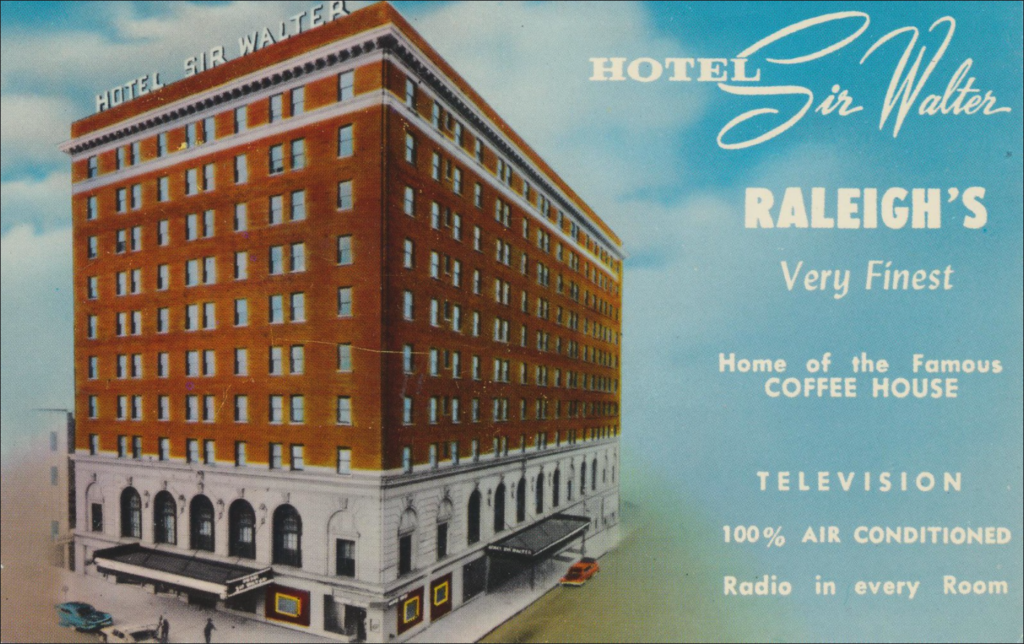

Not that I felt unsympathetic — I was simply too excited by the fact that we were heading for Raleigh and the Hotel Sir Walter on downtown Fayetteville Street, where we would soon meet our visionary governor, Terry Sanford, and Vice President Lyndon Johnson.

This flat that needed changing: my father, who never seemed to be in a hurry, was in even less of one now — he had been diagnosed with MS and now walked with a slight limp and carried a black, silver-handled cane. Still, he was relaxed and confident, and he was quite strong — those many years he had gone swimming in the ocean at dawn, the quarter mile between our Kitty Hawk cottage and the old Kitty Hawk Fishing Pier and then back, all helped him.

He had no trouble with the tools, or the flat and the spare, and he clearly had no worries about what time we might see the governor, let alone the vice president.

When at last he got back behind the wheel of his own car, I saw that he had scarcely broken a sweat, had not gotten his suit or shirt dirty at all, and only his hands, sooty from handling the tires, needed washing.

“Why did we have to stop?”

“She needed help, son.”

“Somebody else could’ve done it.”

“You don’t know that — not a lot of traffic on this road.”

“But sooner or later —”

“No,” he said evenly, “it fell to us.”

To us. Suddenly he had brought me into his Good Samaritanism, as if I, who would have let the brief mission go to someone else, had been a party to it, and I was all at once both proud to be his son and proud of something I did not even do: we had helped a woman in distress. “And now she’s on her way again,” he said.

Next thing I recall, we were in Raleigh, at that time just a great big country town, and he had found a men’s room off the Sir Walter’s lobby and washed his tire-dingy hands, and then we were in a hall upstairs, where a very short line was controlled by a couple of secret service men and state troopers, almost natty in their gray shirts and crimped, charcoal Smokey hats.

At our turn, the governor and the vice president seemed extraordinarily relaxed, informal, friendly. Just the four of us in that room, where, mostly, my father bantered with the two leaders — he already knew well and supported Governor Sanford, and the ham-handed Texan seemed little different from the soybean and cabbage and hog farmers my father politicked with back up in Pasquotank County, where he was solicitor.

“Are you a good Democrat?” the vice president asked me.

“Yes, sir.”

Soon we were off to a cocktail party at a home elsewhere in Raleigh. I watched the clock move slowly toward the time of the Jefferson-Jackson Day dinner, a fifty-dollar-a-plate affair being held in one of North Carolina’s most modern buildings, the glass-walled, swooping-arched Dorton Arena at the fairgrounds, where they held rodeos and rhythm-and-blues concerts when the politicians were not in there holding sway.

I devoured, if not inhaled, my high-piled barbeque plate, dearly wishing for another one, had they not been so expensive. This was hardly my first mouthful of chopped pork cooked with holy smoke, but it was certainly my first taste of political fundraising.

Yet my relish toward my plate held no candle next to Lyndon Johnson’s toward his crowd — he was proud to be here, he said, proud to be an American, and so was President John Kennedy, and they were two proud Americans who couldn’t wait till the 1964 election, when they would be back in North Carolina, this proud American state, which they intended to carry by a landslide, because North Carolina was full of great Americans, like every one of you all here tonight!

We shook a lot of hands, talked loud and proud about the day, piled back into the Buick and kept on talking. “Would you like to go to Washington?” my father asked me after a while, meaning to go be a page in Congress. Yes, I would, of course I would, I said, in the grip of a political swoon — why shouldn’t I wish to go to Washington?

I had worked in Raleigh, had met the governor, had now shaken hands with the vice president, and yes, I would very much like to go to Washington. And so we rolled our way on back the thirty miles west to Chapel Hill, and every once in a while when we would laugh, he would pat my knee, as he always had when it was just us two riding in the car, and I am glad I did not feel I was too old for that.

For the main event of the day, as it turned out, was not the politicians or the Hotel Sir Walter or the cocktail party, or the lusty handshaking and backslapping of the hundreds at Dorton Arena bonded by barbeque and yellow-dog Democratic faith. But I knew what it was before my head hit the pillow that night.

It was my father, and his kindness to the woman beside NC 54 near Nelson.

It was his kindness to me, a mere fourteen-year-old boy who scarcely knew how to act with him, as he spoke with me in the car, treating me as an equal.

It was his kindness, period.

___

This excerpt appeared in the October 2021 issue of WALTER magazined. From NORTH CAROLINA: LAND OF WATER, LAND OF SKY by Bland Simpson, photography by Ann Cary Simpson, Scott Taylor, and Tom Earnhardt. Copyright © 2021 by Bland Simpson. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org