Downtown music venue The Pour House expands its music ecosystem again, this time with a small-batch record press.

by David Menconi | photography by Taylor McDonald

Pour House Music Hall co-owners Adam and Lacie Lindstaedt will tell you that the only thing that got them through the big pandemic shutdown was their record shop. They opened it upstairs in the venerable downtown Raleigh space in 2019, and selling records online made survival possible during the dark days of 2020 and 2021.

In the process, however, they noticed that a surprising amount of the vinyl records they sold had been pressed overseas. Getting stock could take months, even years. And that led to another new Pour House venture. “Looking into our other options,” says Adam, “it felt like a natural segue for us to go into widget-making.”

That was the genesis of Pour House Pressing, the Triangle’s only full-scale record-pressing operation and one of just a handful statewide. It’s a boutique operation with Adam running the floor as the “Party Boss” and Lacie as client manager or, as she describes it, “Organizational Freak — an advocate for the endangered art of the phone convo.” Almost all of their clients are area performers selling their own records themselves, at gigs or through independent record stores.

“We don’t want to be pressing a million copies of Rumours,” says Lacie, referencing the Fleetwood Mac best-seller. “We want to be here for the local acts. There are gigantic plants that can put out 50,000 records a day, and that’s where Taylor Swift should go.”

Overhearing the name of everybody’s favorite pop star, 5-year-old Desmond Lindstaedt’s ears prick up and he asks if they’ll be pressing records for her.

“No, Desmond,” Lacie tells her son with a laugh. “We’re not gonna make a Taylor Swift record. We’re here for the independents.”

Pour House Pressing occupies a former taxidermy warehouse in an industrial park about 5 miles east of their nightclub on Blount Street. Getting it started took a do-it-yourself crash course in industry infrastructure, years of work and planning, plus hefty business loans.

Although vinyl is a vintage format, pressing records is a complicated, detail-oriented process that requires both boiling-hot and cold water, as well as precise timing on the pressing machines. The plant’s operations began in the spring of 2024 on two presses, one automatic and one semi-automatic.

Pour House’s current capacity is 1,400 records per eight-hour shift, with orders ranging from 100 copies up to several thousand for bigger jobs. A range of extras are available, including gatefold covers and rainbow colors on the vinyl itself.

“We recommend at least 300 because your return on investment is so much better,” says Adam. “At 100, you’re looking at more than $20 apiece. At 300, it costs about one-third that per copy.”

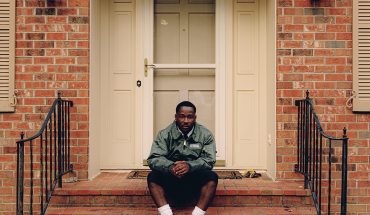

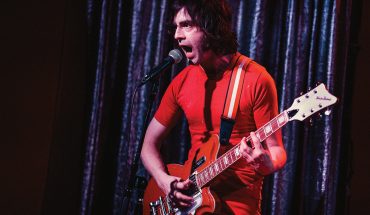

Among the local acts who have had records pressed at Pour House are rock bands Jack The Radio and PKM and rapper/poet Shirlette Ammons, who enthused that it’s “awesome to have a quality vinyl pressing plant right here in our backyard.” Phonte Coleman of Little Brother/Foreign Exchange even came in to press a few copies of his latest release himself.

“I admire how much time they’ve put into this,” says Coleman, whose 2024 EP Pacific Time 2 sold all 300 copies through preorders in less than a day. “Pressing vinyl is an artisanal craft, like blacksmithing. If you don’t pass it on, the art form is lost.”

For many years, vinyl records were the industry-standard format, before yielding to cassettes in the 1980s and compact discs in the 1990s. When major labels shut down their pressing plants, the format nearly died.

Online streaming is the focus these days for the Taylor Swifts and Beyoncés of the world, but vinyl has come back as the physical format of choice. CD sales have declined enough for vinyl records to have outsold them in 2022 for the first time since 1987. That leaves Pour House in a solid position.

“The club, store and pressing plant are all part of the same ecosystem,” says Adam. “You can play a show at Pour House, record it, press it and sell it at our record store. Now we’re involved in three different career elements.”

Still, long-term sustainability will be a challenge. Adam puts Pour House Pressing’s monthly break-even point at almost $100,000, and that’s without either Lindstaedt taking a salary yet.

“We’re still running on the fumes of last year’s tax refund,” Adam says.

Nevertheless, it’s an exciting business to be in.

“We’ve never made a hiring announcement, and we still have 300 resumes on file,” says Adam. “A lot of teachers and doctors are looking to get out of their jobs. It’s a cool thing. But it’s still a factory, manufacturing plastics, and you have to get it just right.”

This article originally appeared in the November 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.