Just off of Oberlin Road, two shaded acres honor a complicated, nearly forgotten chapter in Raleigh’s story.

by Susanna Klingenberg | photography by Liz Condo

Tucked just off Oberlin Road, beyond the hum of the Village District, lies a pocket of green that holds echoes of another time. Opened in 2024, the 2 acres of Latta University Historic Park have become a neighborhood gathering spot. But the space also holds a nearly forgotten chapter of Raleigh’s past — a story of resilience, ambition and the complicated layers of Southern history.

Latta University Historic Park was once a bustling part of Oberlin Village, Raleigh’s largest and longest-surviving freedman’s village. A map of the area from the 1860s shows roads named Emancipation Alley and Lincoln Avenue, and in its heyday, Oberlin Village stretched across 149 acres, with 170 families who built farms and shops, churches and businesses, a school and a cemetery.

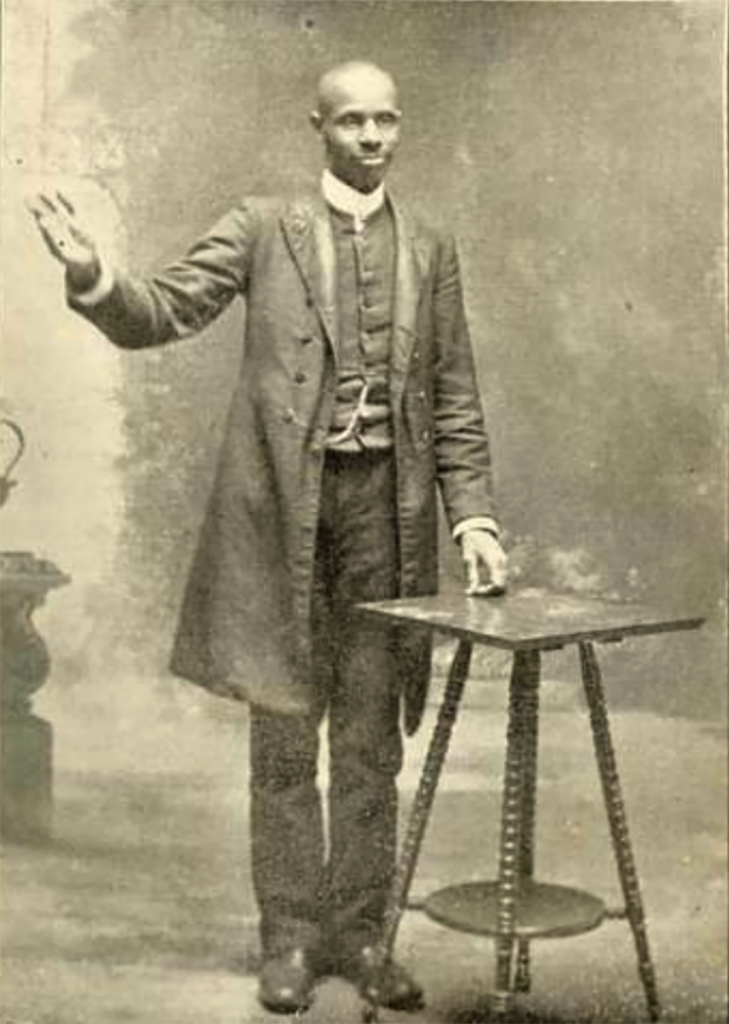

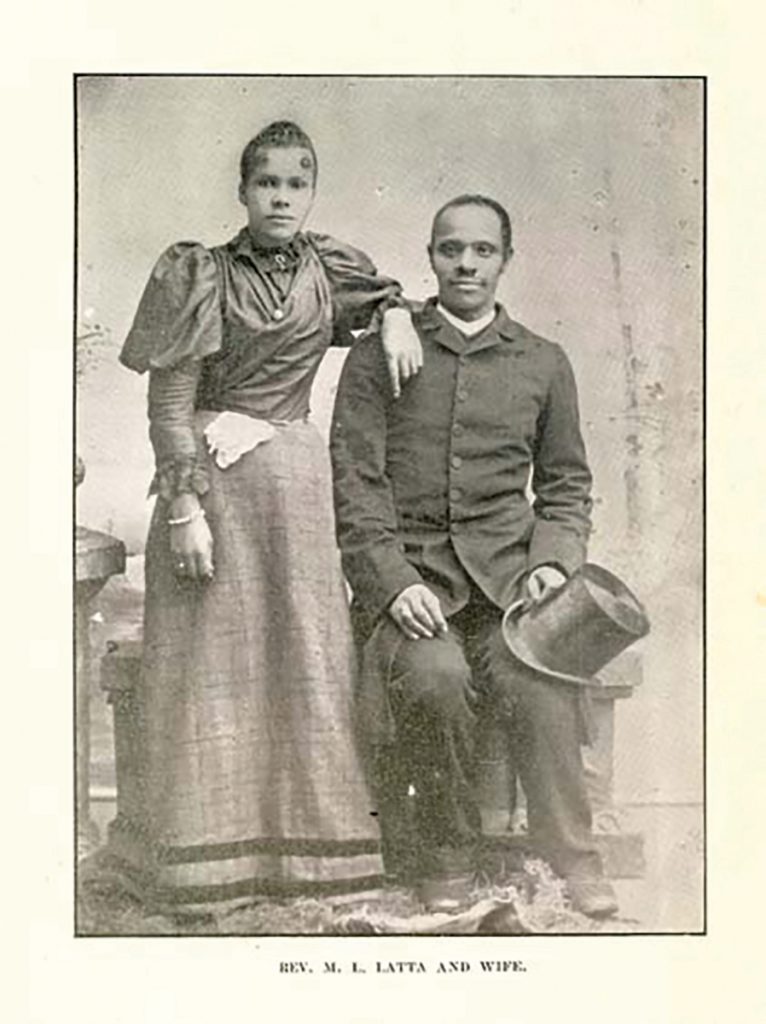

Especially in its earliest days, Oberlin Village was something rare and powerful: a place of safety, opportunity and abundance in a world that made freedom hard to hold onto. It was into that atmosphere, in the late 1800s, that Reverend M.L. Latta emerged.

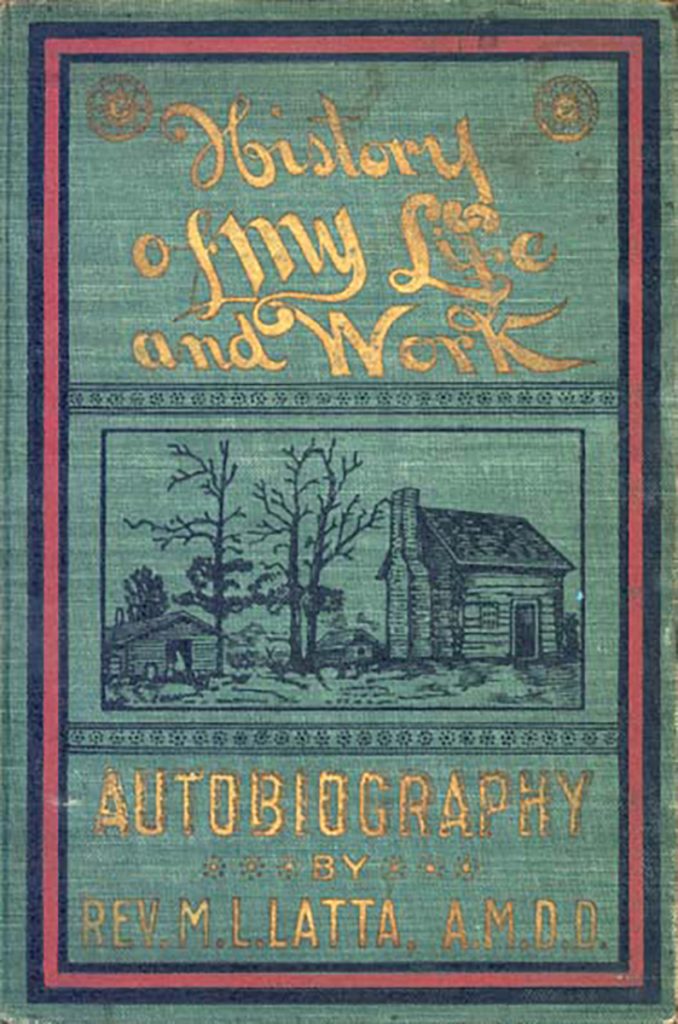

Born into slavery on one of the Cameron family plantations, Latta’s childhood was shaped by struggle. After his father and elder brother died, Latta was responsible for helping raise his 11 siblings. In his autobiography, Latta says whippings were frequent and food was scarce: “I would be just as hungry when I got through eating, as I was when I commenced.”

Latta attended school on and off, balancing studies with heavy work responsibilities. He enrolled at Shaw University at age 15 with, according to his autobiography, “ten cents in my pocket.” He worked odd jobs to pay his tuition and board, eventually earning a teaching certificate. For Latta, education was more than self-advancement: it was a pathway for progress.

It was in that spirit that in 1892 he founded Latta University, a coeducational school for formerly enslaved people and their children, on the space that is now Latta University Historic Park. Unlike today’s four-year universities, “Latta University was modeled more closely on Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute,” explains Doug Porter, City of Raleigh program director for historic sites.

According to Porter, students at Latta University studied vocations and trades such as blacksmithing, bricklaying and wheelwrighting, alongside academic subjects like physics and Latin for those planning to become teachers or pursue higher education. It even included a kindergarten for orphans and children of formerly enslaved parents. At its height, the university boasted 26 buildings and hundreds of students. Latta became an advocate for the education of formerly enslaved people, and the university survived nearly entirely on donations. He traveled across the United States and abroad; in his autobiography Latta even recounted a meeting with Queen Victoria.

But history is rarely tidy, and Latta’s legacy is no exception. His self-published biography is considered a mix of truth and fiction. Newspaper articles from the time indicate that some Oberlin residents distanced themselves from Latta; he was also accused of misrepresenting the university and embezzling money.

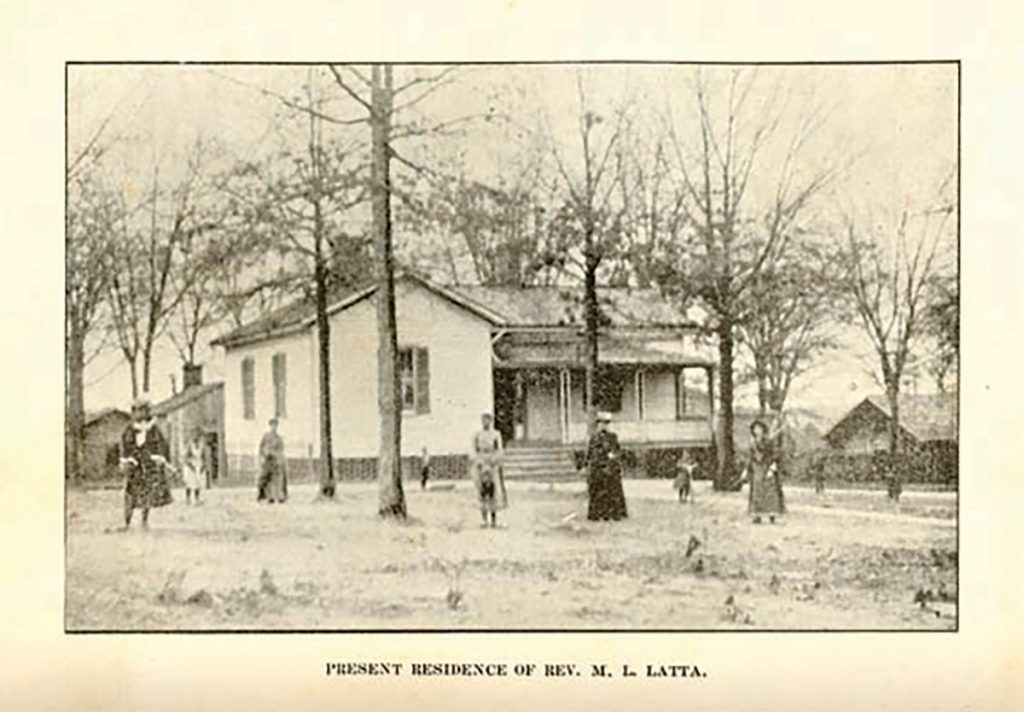

His tarnished reputation and mismanagement of funds hastened the university’s decline. By 1922, Latta University was shuttered, the land was sold and the buildings began falling into disrepair. Over the years, the campus was consumed by fire and redevelopment. The final surviving building from the University, the Latta family home, burned down in 2007. For years afterward, the university largely faded from memory.

When the land that is now Latta University Historic Park was deeded to the city, advocates rallied to ensure its history was not erased by development. “As an African American, it’s pretty unusual to be able to trace family history back that far,” says Brandi Neuwirth, Latta’s great-great-granddaughter. “It’s given me a sense of responsibility for the land, that it continues to help people.” Neuwirth served on the Citizens Planning Committee for the park. The group also included historians, planning experts, neighbors and individuals with a first-hand connection to the park, as well representatives from the nonprofits Friends of Oberlin Village and Latta House Foundation.

“We go into the community engagement phase of planning with a pretty blank slate,” says Emma Liles, City of Raleigh capital project manager, who led the committee. “We wanted to honor the history we couldn’t see anymore in the physical space.”

The planning process sparked debate over how best to tell Latta’s story, but over time, two priorities emerged: preserve the history of the land and preserve its serenity. On the 2-acre site, visitors today can trace the Latta House footprint in granite. Six interpretive signs, developed with input from Neuwirth and local historians, highlight artifacts like family photos, census records and findings from archaeological digs, including slate and writing tools, cutlery and coins. Plans for a second phase include an interpretive pavilion to explore the university’s story more deeply.

Neuwirth believes the park now captures the spirit of her ancestor’s mission: “We wanted it to tell the story, but we also wanted it to serve the community, because that was really the point of Latta University. And I think it does that.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2026 issue of WALTER magazine.