Dr. Lindsay Zanno takes us beyond the glass walls of the Paleontology Research Lab

by Ayn-Monique Klahre | photography by Joshua Steadman

Click on image to enlarge and start slideshow.

You’ve probably gotten a peek into the Paleontology Research Lab inside the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences; its walls, after all, are made of glass. From the outside, you can see the quiet bustle of researchers and grad students chipping away, literally, at ancient fossils. That’s all fascinating on its face, but if you’re lucky enough to step inside, like we did for our photoshoot, you’ll realize that—much like any excavation site—what you see is just a hint of what you’ll find beneath the surface… or in this case, beyond the walls.

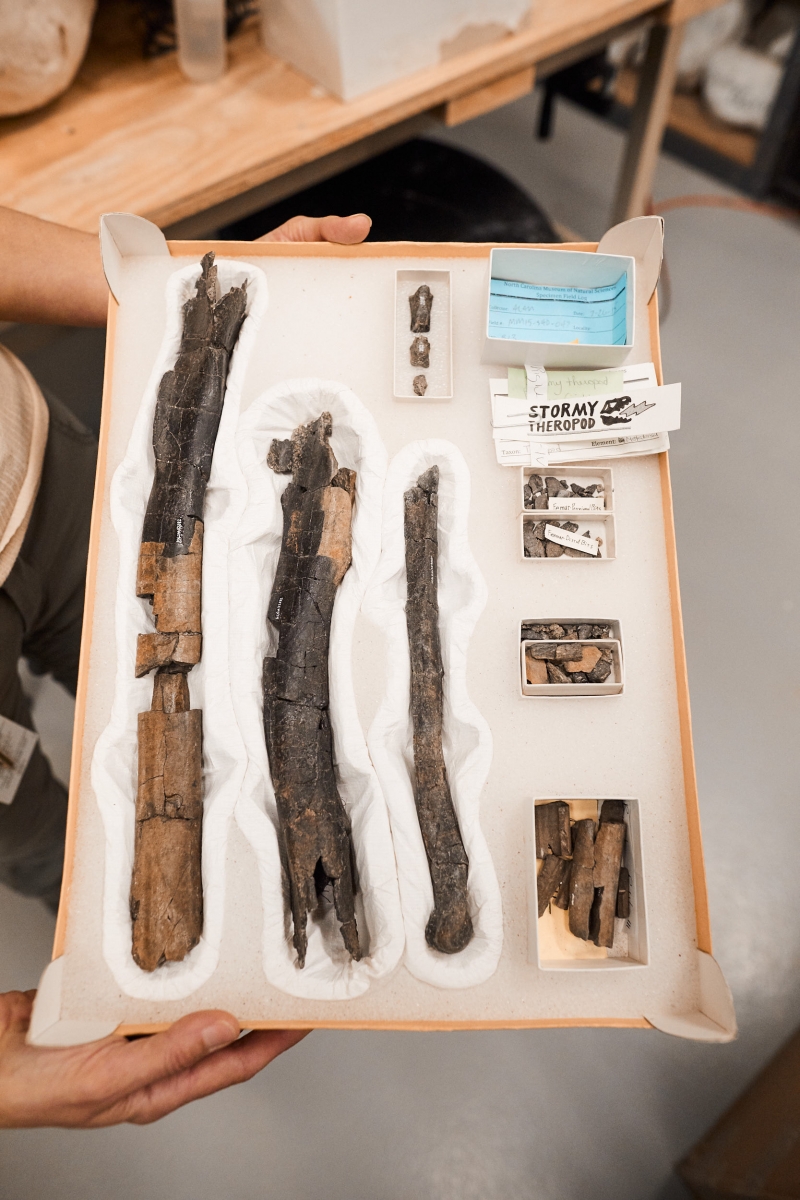

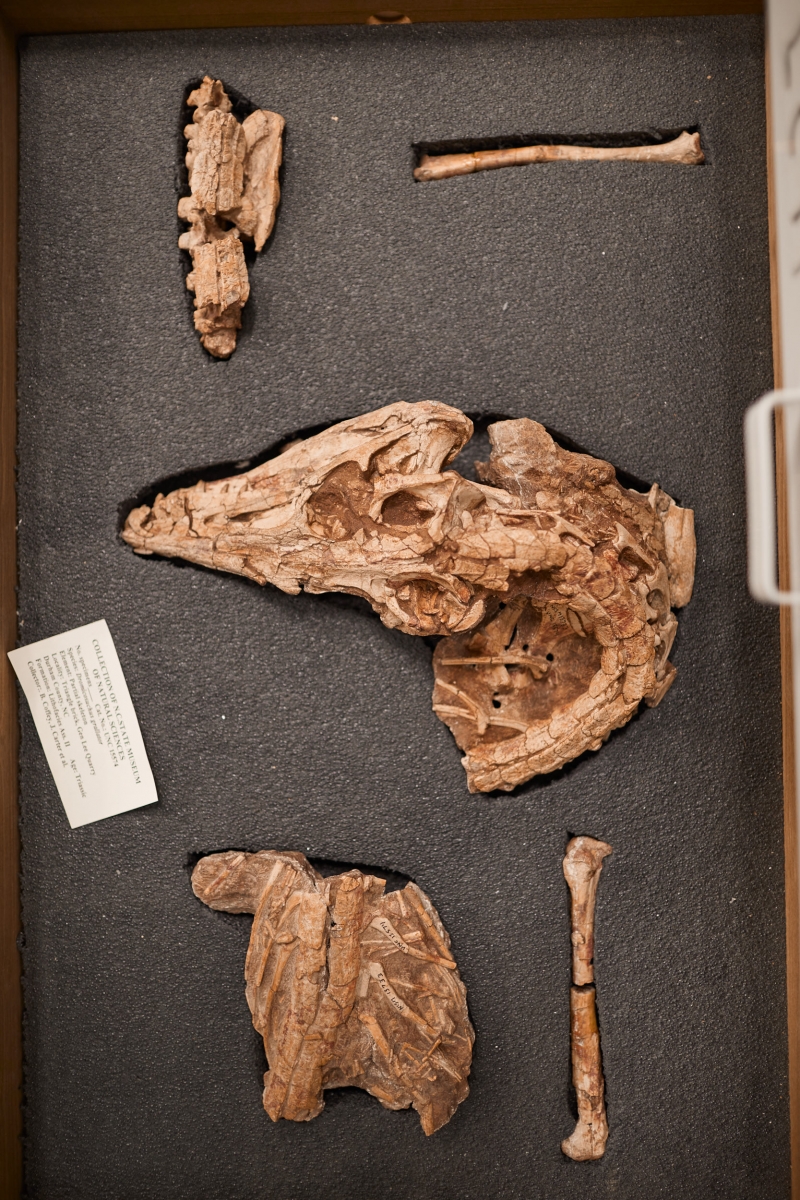

Dr. Lindsay Zanno is the head of the Paleontology lab, where she supervises about six staffers and students at any given time, in addition to teaching at N.C. State University. Zanno was brought on in 2012 to raise the visibility of the research going on at the NCMNS, and she made a big splash this past February when she announced the discovery of a new dinosaur, Moros intrepidus, named the “Harbinger of Doom” because the tiny tyrannosaur helps bridge the fossil gap between the smaller dinosaurs of the Jurassic period and super-predators of the Cretaceous period. The fossils that led to the discovery are on display at the front of the lab for all to see, the fruit of more than seven years of excavation and research after she first spotted the bones at a site in Utah. “I love the field work, the adventure and excitement of finding something new,” says Zanno.

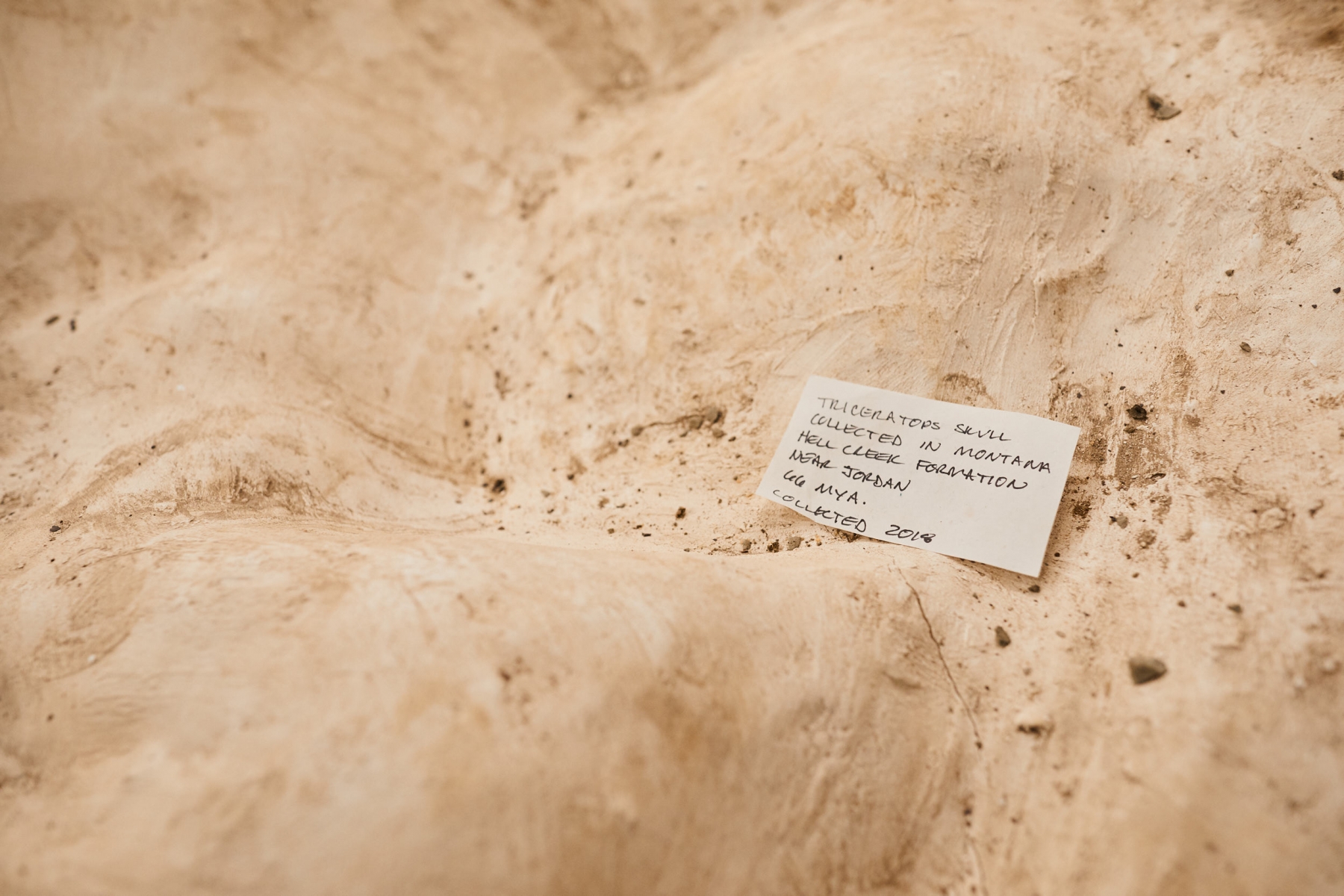

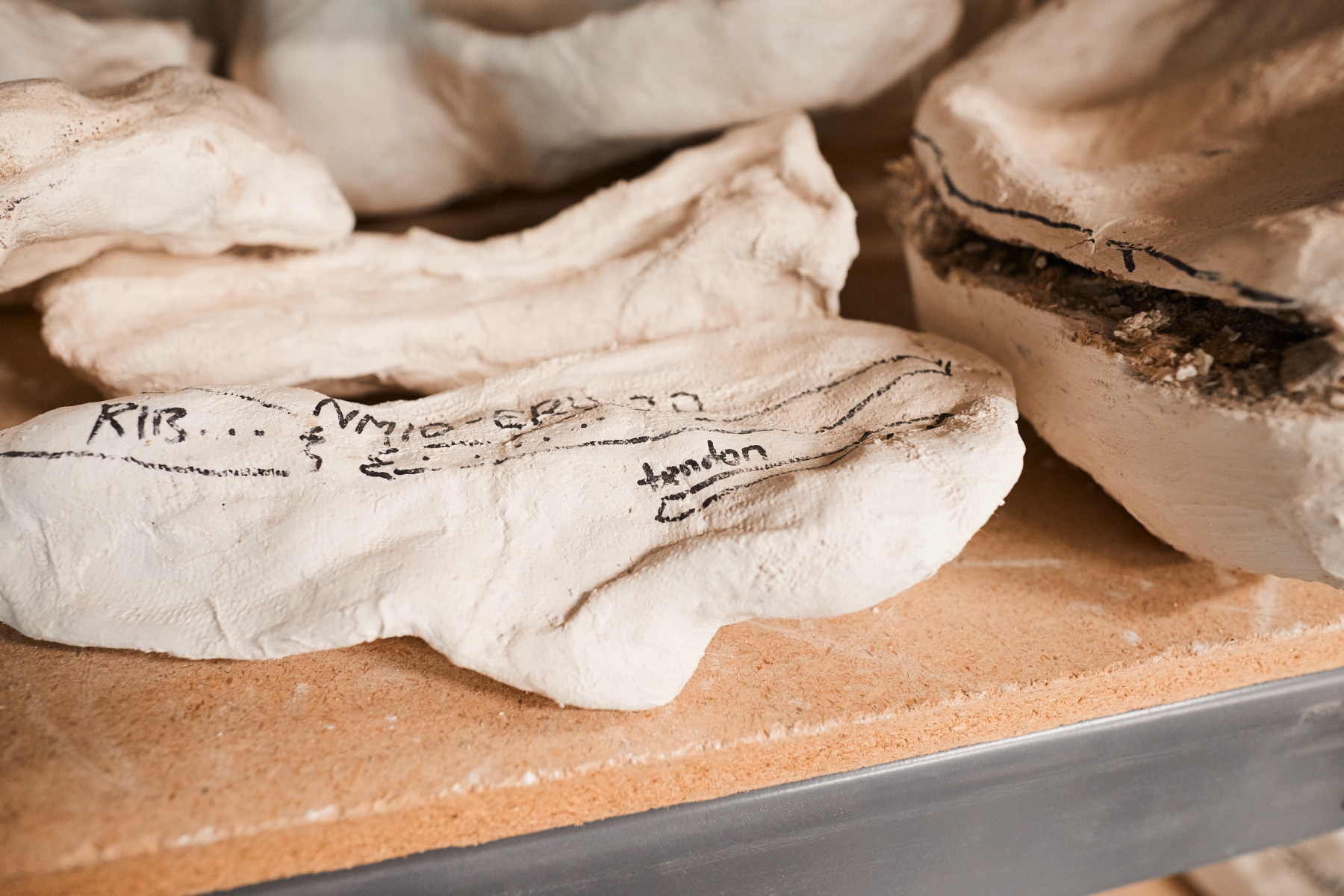

Inside the lab, there are about 25 research projects going on right now. Front and center, you see oviraptorosaur eggs that are being excavated—once that’s done, the eggs will be sent to N.C. State for a CAT scan to see if anything is still preserved inside. In the middle of the room is a giant triceratops skull, still encased in a protective jacket, that Zanno found in Montana in 2016. “I’d been walking for hours and really didn’t want to go down this hill, so I decided to stand there and just look. And I saw something, just about six inches of fossil sticking out. As we kept digging, we realized it was a paleontologist’s dream,” she says. It took two years to get the permits and fully excavate the nearly-intact skull, then they used a helicopter to airlift the 1,400 pound fossil back to civilization. Deeper inside the lab is office space; here Zanno and her team write up research and grant applications, study specimens, create models and more.

The most hidden part of the lab is in the basement. That’s where all the fossils are stored, more than 4 million specimens that have been discovered or sent in by others (once they receive a fossil, they’re obligated to store it in perpetuity). While they can’t loan anything out, they invite other researchers to use their collections. Because, Zanno says, while the field work is exciting, the best part comes once the research is done. “I love the moment of discovery when all the data goes through!”