“David’s story is unique in a sense that we now have an era of publicly celebrated chefs – food gets so much attention – and David represents the not-so-glamorous side of the food world. It’s a commitment. A chef gives up a lot, missing holidays and birthdays. David, at his age, is still working, and it’s a real sacrifice, but it’s become his identity,” says Vansana Nolintha, owner, Bida Manda.

by Dean McCord

photographs by Lissa Gotwals

For nearly 50 years, chef David Mao has been on a journey to a destination that cannot be found on a map; a trip that cannot be measured in miles. It has been a sojourn of the heart and soul. It took the son of Chinese immigrants from his home in Vietnam across the world to North Carolina. Raleigh wasn’t the destination Mao had planned, but it’s where he found his true home, in a restaurant that returned him to his childhood, where he can share the food of his family and of his youth. He has found peace.

It wasn’t easy.

When young David Mao came to Raleigh in the mid-’70s, the diverse Triangle food scene we take for granted today was non-existant. The Laotian, Korean, Thai, Vietnamese, Malaysian, Hunan, Szechuan, and Cantonese cuisines available today hadn’t yet arrived. To find any Chinese food that was actually eaten in China would have been a struggle at best. Chow mein, chop suey, and egg foo yung comprised the “Chinese” dishes on offer.

Into this unlikely scene, Mao brought his talent and his drive. He worked in a few local kitchens and then opened his own restaurant in Cameron Village – the first step to reclaiming his home. He went on to create the popular The Duck and Dumpling eatery on Moore Square, and today presides over David’s Dumpling and Noodle Bar at the corner of Oberlin and Hillsborough streets.

None of it would have been imaginable when, after years of war, the Communist takeover of his country, and persistent discrimination of Chinese, Khi Ho “David” Mao realized he needed to get out of Saigon. Originally from the Fujian region of China, his family had fled unrest at the beginning of the 20th century for northern Vietnam. When it became a divided nation, David’s family left the Communist-controlled North for Saigon.

Fateful meeting

Saigon was where Mao learned to cook. When he was 15, he began working at his oldest brother’s restaurant, The Eskimo, in Cholon, the city’s Chinatown district. A young American army officer, Hal Hopfenberg, had his first meal at The Eskimo in 1966. He was particularly taken with the hot-and-sour soup, which was unusual in that it had a clear broth, because it contained no soy sauce. Hopfenberg inquired about the soup. A burgeoning gourmet, Hopfenberg wanted to learn how to make it, and Mao taught him. In exchange, Hopfenberg, who had his doctorate in chemical engineering from M.I.T., gave Mao lessons in algebra. “By the time I left Saigon,” Hopfenberg says, “he could factor polynomials and multiply them back to see that he was right, and by the time I left, I could make the soup. He hasn’t used algebra since, but I still make the soup. I won that trade.”

Neither man ever imagined that the chance encounter between a loquacious New Yorker and a soft-spoken Chinese immigrant in Vietnam would lead to a lifetime friendship.

Hopfenberg was only in Vietnam for nine months, but before he left, he knew his friend wanted to move to the United States: The war between North and South Vietnam was becoming more violent, and concerns of Communists controlling South Vietnam were persistent. But Hopfenberg had no idea how hard the process of getting Mao here would be, nor did he imagine where Mao would end up.

Six years later, in 1972, Mao immigrated to the United States. It was a year before the last U.S. forces left Vietnam, and three years before the Communists seized control of Saigon. His destination was Raleigh, where Hopfenberg and his family were living. Mao moved in.

He went to work in several restaurants, including the local Chinese place, Far East, and a French restaurant co-owned by Hopfenberg. But Mao didn’t want to be an employee. He wanted to own his own place.

Opened in 2010, David’s Dumplings and Noodle Bar serves authentic Vietnamese and Chinese comfort food.

With some advice from Hopfenberg – and with some assistance from the York family in obtaining a lease in the Cameron Village shopping center – he opened the Mandarin House restaurant there. The menu was not cutting-edge. It wasn’t what David wanted to serve, but it was what people wanted to eat: basic, straightforward Chinese-American. “For the most part, I served what Raleigh was ready for,” Mao said. At the same time, there on the menu was the hot-and-sour soup. And his signature half-fried dumplings: pork-filled potstickers that are made by hand, steamed, and then quickly fried in a wok. But the dumplings weren’t a big hit – at that point, they were too edgy for the local palate.

Nevertheless, the Mandarin House was a welcome addition to Raleigh. It served delicious, comforting food, and locals loved it. “Mandarin House was a second home for me,” says Gus Gusler, owner of The Players Retreat and Mao’s current restaurant neighbor. “I’d have dinner there at the bar and talk with David and say, ‘Fix me something.’ Which he did.”

Over time, other, more “authentic” Asian restaurants opened in the Triangle, and Mao had competition for the first time. In 2001, rising Cameron Village rent forced Mao to close, leading him to his second major restaurant – and his second compromise.

He opened The Duck and Dumpling in 2002 downtown across from Moore Square in a partnership with real estate developer Greg Hatem. “I wanted to do something that was nicer, with better dishes, not strictly Chinese,” Mao says. “I added some Vietnamese food and created some new dishes.” The restaurant was hip and stylish, aimed at a younger clientele. But despite solid reviews, the economy soured, as did the relationship with Hatem. The Duck and Dumpling was not economically sustainable, and Mao departed. Suddenly out of a job, Gusler found Mao seated at the end of the bar at The Players Retreat, feet propped up, saying, “Forced early retirement.”

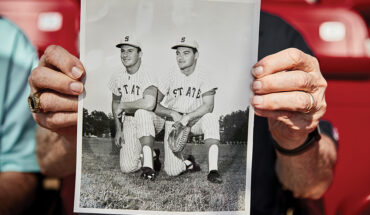

Photographs and postcards provide a visual timeline of Mao’s journey from Saigon to Raleigh. A card from Mao’s first restaurant, the Mandarin House, provides more details about the dumplings – “an exotic mix of ground pork, Chinese vegetables, green onions, white pepper, soy, salt, and ginger. Half-fried.” Snapshots show The Ekimo restaurant in Saigon, where Mao learned to cook and also met Hal Hopfenberg.

Culinary home

Of course, Mao was not retired. “He’ll work seven days a week forever. Forever,” Hopfenberg says. Mao needed to keep working, but he also needed the right kind of restaurant, where he was cooking as much for himself as he was for his customers. Where no compromises would be made to satisfy the conceits of trendy or hip. Where the dumplings and noodle dishes of his youth were the featured attractions, not the afterthought.Vietnamese dishes would also be essential. This time, there would be no compromises with his restaurant: He could return to his culinary home.

David’s Dumpling and Noodle Bar opened in 2010, and with that, Mao reached his destination. This time, Raleigh was ready.

It was honest food straight from Saigon and the kitchens of China, nothing flashy. Vansana Nolintha, owner of the super-popular Laotian restaurant Bida Manda, respects Mao’s return to his roots: “We are all looking for authenticity, and David’s food is exactly that. The food is not trendy, and it takes a lot of courage not to do fusion food. David’s food is not necessarily designed to be creative, but instead to reflect a sense of home.”

Nolintha frequents David’s Dumpling and Noodle Bar, joining buddies from N.C. State most Tuesdays, trying to get away from the hustle and bustle of downtown. “I appreciate that David continues to explore traditions, offering items that have been cooked the same way for a long time. I’ve always looked up to him for how he presented his food as a reflection of his journey.”

Mao makes dumplings from scratch each day. When devoted customer Mebane Rash thinks of Mao, it’s his dumpling-making that comes to mind: “I will always remember his hands, dusted with flour from his dumplings.”

His journey has been successful, but it’s never been easy. Even today, at 72, he works “six-and-a-half days a week,” helping with the prep work and making his trademark dumplings. He hasn’t taken a vacation in 15 years. “Maybe I’ll travel, visit my brother in Seattle or go to Vietnam. But it’s not a huge desire right now. I like to take care of my customers.”

Mao is certainly gracious, but a hospitable host alone doesn’t make for a successful restaurant. People come to be soothed by this cooking. To be warmed in the belly and soul. “This is comfort food for us,” said Mebane Rash, a regular who has been bringing in her family for years.

Everyone has their favorite dish. For Hal Hopfenberg, of course, it’s the hot-and-sour soup. Nolintha particularly loves the fried rice. “He uses cold rice made the night before. The dish has no soy, so the color is completely white. The key is that he uses grease from the chinese sausage to fry the rice and salt for seasoning. You can taste all the individual components with that background flavor from the sausage fat.”

And then, of course, there are the totemic dumplings. “I’m a fried dumpling freak,” Gus Gusler says, “seeking them out wherever I go. And David’s are the best.”

But Mao’s biggest fan might be a boy, Mebane Rash’s 14-year-old son, Wells Whitman. Mao has always paid particular attention to his younger customers, including Wells before he had even started school. In part because of this connection, Wells decided to take Chinese in kindergarten. He also traveled with his family to China, sampling fried dumplings at every possible stop, trying to find some that were better than Mao’s. None compared. “The best dumplings in the world are here in Raleigh at David’s Dumplings,” he wrote in a report for school. “The outside is just perfect – softer and not too crunchy when you bite into it, the inside tasty and juicy, with the most delicious blend of seasonings, and a special sauce for dipping.”

Even a young American boy understands: David Mao’s food is special. Because it’s the food of his family, made from the heart, reflecting a time when Mao himself was the same age as Wells Whitman. A time that marked the beginning of a half-century journey where the destination was also the place he left. And he found it, his new home, right here on the corner of Oberlin and Hillsborough.

Hot-and-Sour Soup

This version of hot-and-sour soup contains no soy sauce. The “hot” comes from ground white pepper and the “sour” from white vinegar. Hal Hopfenberg had to barter algebra lessons with David Mao to get this recipe, but Mao has softened up over the years: no trades required.

The recipe contains two somewhat unusual ingredients: dried wood ear mushrooms and dried lily flower stems, both available at local Asian stores. The dried lily flowers are the unopened flowers of the daylily plant, and they give the soup a bit more of an earthy flavor.

2 quarts chicken broth, preferably homemade

½ teaspoon white pepper, ground

¾ cup white vinegar

¾ teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons sugar

2 eggs, beaten

1/3 cup cornstarch, stirred into ½ cup cold water

½ cup dried wood ear mushrooms

½ cup dried lily flower stem

½ cup bamboo shoot strips

5 ounces soft tofu, cut into ¼-in. strips

Handful of scallions, chopped

Sesame oil

Cover the lily flower stem with boiling water. Let soak for at least one hour. Soak the mushrooms in warm water for about 20 minutes. Chop each into long threads.

Bring chicken broth to a boil, add vinegar, pepper, salt, and sugar and mix well.

Add cornstarch slurry slowly, while stirring the soup, until it reaches desired thickness. It should be a little thick, but not sauce-like. You probably will not use all the slurry.

While stirring, slowly add beaten eggs. Add mushrooms, lily flower, bamboo strips, and tofu.

Garnish with chopped scallions and a drizzle of sesame oil.

Fried Rice

Like his soup, David Mao’s fried rice contains no soy sauce. The primary flavors come from salt and the residual fat from Chinese sausage. Mao uses Kam Yen Jan brand, which is sold in Asian markets, typically in packages of 12.

1 pound peeled and deveined shrimp (21-25 count white shrimp)

4 sticks Chinese sausage, thinly sliced diagonally

½ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon ground white pepper

3 eggs, beaten

4 cups white rice, cooked and then cooled on a cookie sheet

½ cup vegetable or soybean oil

2 tablespoons chopped scallions

In a large wok or skillet, heat oil on medium high, stir in shrimp and sausage, and cook for 1 to 2 minutes, until shrimp is barely cooked. Do not overcook shrimp.

Remove shrimp and sausage from wok, set aside. Drain oil from wok, but leave enough residue to cook rice.

Add cooled rice to wok and cook until warmed through. Add egg, salt, and pepper, and stir until egg sets and rice is hot.

Toss shrimp and sausage back into wok and stir until heated through.

Remove from heat to avoid overcooking the shrimp.

Garnish with chopped scallions.