University Park plant enthusiast Milos Novak draws on his experience growing up in socialist Czechoslovakia to tend his artful bonsai.

by Addie Ladner | photography by Liz Condo

Milos Novak grew up in the village of Dolní Dobrouč in Czechoslovakia. He spent his free time wandering the mountains nearby and the streams and forests that wrapped around them, fascinated by the shapes that Mother Nature would create in the larch and beech trees that grew alongside the cliffs.

Raised during the country’s socialist regime of the 1970s and 80s, his family had little income and grew their own produce. He can still recall his late hardworking father and grandfather’s bountiful plots of carrots, tomatoes and apple, plum and pear trees that he’d help graft for production. “I learned early on that you could control the growth of a tree, and how to graft and prune just right,” Novak says. “I learned from watching my dad, who learned from his dad.”

During high school, he’d bike 15 kilometers a day to work in construction, and one day discovered a nearby bonsai nursery. “I had nothing else to do. I love plants so I just popped in,” he says. “That’s when I saw my first bonsai.” A Japanese art form, bonsai are the product of growing miniature-sized plants, trees and shrubs — typically around 12 inches tall — by vigilantly controlling their roots and branches. It was the only nursery of its kind in the area, and Novak became fascinated by this unique and artful way to grow trees. There, he bought the book The Complete Book of Bonsai by Harry Tomlinson, which he has since read front-to-back dozens of times to perfect his craft.

From Tomlinson’s book, Novak learned that there are two ways to get a bonsai. These diminutive plants can grow organically, trimmed or constrained by wind, animals or difficult terrain. Or it can be slowly, carefully crafted by human hands. “Pretty much any tree can be manipulated into a bonsai, a smaller version of itself,” he says.

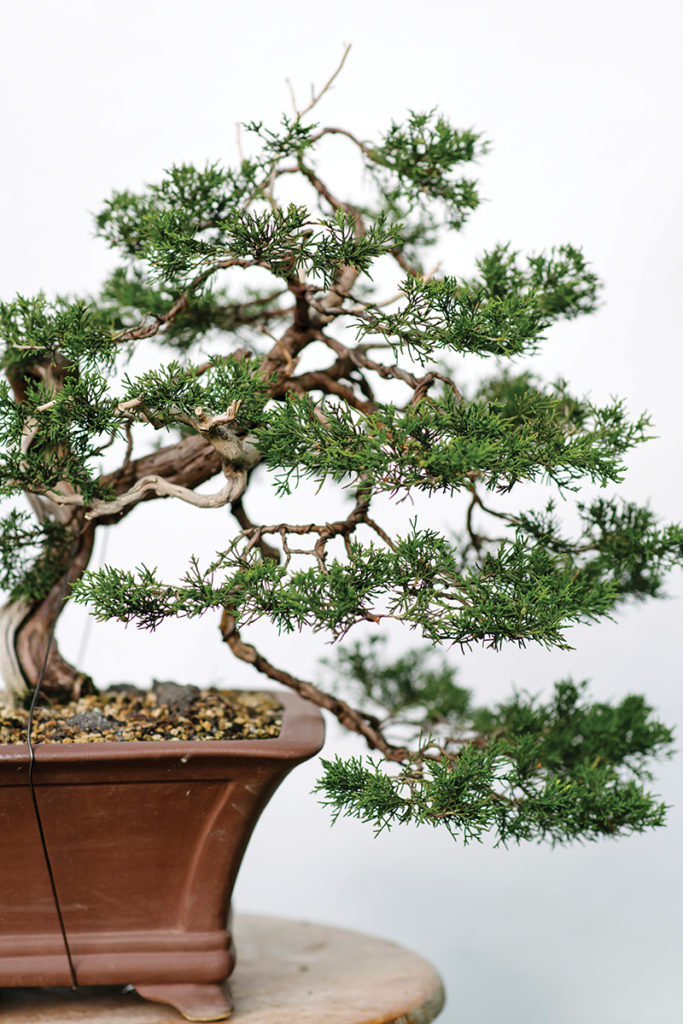

Inspired by the forms and lines of these living works of art, he attempted his first one, a Shimpaku Juniper (an evergreen conifer native to Japan), at age 18. “It wasn’t perfect, but it was good. I just really enjoyed the process,” he says. He kept practicing.

Novak moved to the United States at age 22 to play semi-professional sports, then settled here and started working in construction. He left his first collection back home. He was quick to start a new one: “Even in my first apartment, I’d have my bonsai and little flowers growing.”

For Novak, who’s now in his 40s, this intense hobby is both science and art. “You’ve got to look at the tree and say, What group is this tree in? What is its potential? What about the foliage? What shape? Is this a young and skinny or an old and round tree? What part do I want the front of that tree to be?” he says. “It is an art. I like to look and I can see styles.”

Gently exposing the roots over time, he cultivates branches to grow at certain angles and grafts on new branches to create different shapes. From wisteria to juniper to ficus to cypress, there are few plant species Novak hasn’t raised as bonsai. For each of his plants, he knows how long he’s had it, what its history is and what he wants it to look like. “One Chinese juniper I have is close to probably 100 to 125 years old. Some of my Japanese maples are probably around 40 years old,” he says.

On some of his bonsai plants, you can see metal wrapped around branches and fresh patches of paste from where Novak sealed spots over after removing branches or adding new ones. “If I think a branch needs to go here, I will find a way to graft a branch there,” he says. He tends to his bonsai for at least an hour each day, and sometimes as many as three.

The soil requires attention, too. It needs to be more porous than typical organic matter to allow for good drainage, since the bonsai will spend their lifespan in a shallow ceramic vessel. “My stuff is a mixture of lava rock, pumice and Akadama, a red clay. I special-order and mix it myself,” he says. He minds the plants’ roots, and how they interact with the vessel: “With bonsai, the roots are more exposed, but they are still the tree’s foundation, and you want a strong tree.”

He’s been working on one special bonsai, a petite Japanese Maple, for 10 ten years. “I’m proud of that one. It has a good root base, good taper, good branch structure, an informal but upright style,” says Novak.

Another on display is a tri-colored azalea. To create it, he grafted three different azaleas onto one plant — now it displays dainty blooms in pink, red and white. Though miniature, each of his bonsai is majestic with winding roots, knobby edges, delicate leaves and greenery of different shapes.

Today, Novak houses most of his bonsai collection in a 5-by40-foot wood pergola in his University Park backyard. “At one point, I easily had more than 200,” he says. Since he and his wife Lynn had their daughters Lida and Karlie, his collection has decreased — to no less than 100. (That he can count, anyway.)

Surrounding the bonsai arbor is a wealth of other lush plants: a full-size Japanese Maple, Rhododendron, evergreens and Lynn’s favorite, roses. But other than the roses, Lynn says, the lush garden is mostly her husband’s doing. “Let’s face it, this is all Milos,” she laughs. “It comes naturally to him; he has this artistic side.”

The word bonsai has Japanese origins and loosely translates to “plant-in-pot.” But to Novak, the petite plants are much more. “This is art,” he says. And just like where he came from, “this is a piece of me.”

__

This article originally appeared in the August 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine.