Church hymns, flannel shirts and briar pipes—I share today’s simple pleasures with the generations before me.

by Jim Dodson

A dear friend I hadn’t seen in far too long and I were having lunch outdoors, safely distanced. She sipped her lemony mineral water and noted her relief that a grueling year was finally drawing to a close.

“If ever a year could make you feel old,” she said with a thoughtful sigh, “this was it.”

I agreed, sipping my sweet tea, pointing out that I am living proof of this sudden aging phenomenon.

“How’s that?”

I replied that I was— quite literally—turning into my father and grandfather before my very eyes. This was either scary or wonderful. The jury was still out on the matter.

She laughed. “I think you were probably just born old. Besides, you’re more of an old soul than a grumpy old man.”

This was nice of her to say. I hoped she’s right. In fact, I hoped this sudden aging awareness might not be the result of the year’s tumultuous events—a worldwide pandemic, collapsed economy, record hurricanes and wildfires, to say nothing of a presidential election that ground us all to a pulp—and was merely a case of finally growing old enough to appreciate the way our lives unfold and how we are shaped by the people who came before us.

For the record, two years ago I officially joined the great Baby Boom horde marching resolutely toward their Medicare and Social Security benefits.

Between us and my morning glass of Metamucil, however, I really don’t feel much older than I did, say, 20 or 30 years ago, when I built my own post-and-beam house on a coastal hill in Maine and spent my children’s college funds creating a large faux English garden in the northern woods.

In my 30s and 40s I could work hard all day in the garden—digging holes, planting shrubs, mowing the lawn, rebuilding old stone walls—and simply require a good soak in our huge Portuguese bathtub and a couple of cold Sam Adams beers to put my aging body right.

As my 50s dawned, shortly before we moved home to Carolina 15 years ago, I even tagged along with renowned Raleigh plantsman Tony Avent and a trio of veteran plant hunters half my age to the Great Karoo desert and some of the most remote places of South Africa in search of exotic plants. We were gone five weeks in the bush, much of that time out of touch with folks back home, politely dodging black mambas and angry Cape baboons.

I came home filthy and exhausted, bloodied and gouged, punctured and sprained in places I didn’t even know I had.

In short, it was glorious—the most fun I’ve ever had researching a book—and it only took me a case of beer and a full week of soaking in the bath to fully recover.

Four years ago, as senior citizen status officially loomed, my wife and I decided to downsize and move from the Sandhills to my hometown in the Piedmont, prompting a friendly debate over whether we should move to the old neighborhood where I grew up or the 10 rural acres I had my eye on outside the city.

“I know exactly what you have in mind,” said my younger wife. “You want 10 acres so you can build another post-and-beam house and create an even bigger faux English garden. Problem is, 65 is not the new 25. I know you well. You’ll rarely come in the house and work yourself to death. I’ll come home some afternoon and find you face down in the Virginia creeper.” I laughed off such a silly notion, pointing out it would either be English bluebells or maybe the winter Daphne.

She was not amused. We moved to my old neighborhood a short time later.

Truthfully, I think about my old woodland garden in Maine and that wild African adventure sometimes when I’m working in the modest suburban garden where I now serve as head gardener and general dogsbody, a simple quarter-acre that I’ve completely re-landscaped with or without the FedEx guy in mind.

As a sign of how time may finally be catching up with my botanically abused body, however, it now takes three cold beers, a longer soak in the tub, two Advil and a short nap to get me up and moving without complaint. I suspect my days of sweet tea consumption are also dwindling in favor of mineral water with lemon. In the meantime, the evidence mounts that I am becoming my father and grandfather before my own eyes.

Maybe that’s not, as I’ve already said, a bad thing, after all. My father’s father, from whom I got my middle name, was a lovely old gentleman of few words who could make anything with his hands, a gifted carpenter and electrician who worked on crews raising the first electrical towers across the South during the Great Depression and later helped wire the state’s first “skyscraper,” the Jefferson Standard Building in downtown Greensboro.

Walter Dodson wore flannel shirts with large pockets and smoked cheap King Edward cigars. He gave me my first toolbox one Christmas and showed me how to cut a straight line with a handsaw that I still own. In the evenings, he loved to sit outside and watch the birds and changeable skies, sometimes humming hymns as he calmly smoked his stogie.

Walter’s wife, my spunky Baptist Grandmother Taylor, knew the Gospels cold, but I don’t think Walter ever darkened the doorway of a church. Nature was his temple.

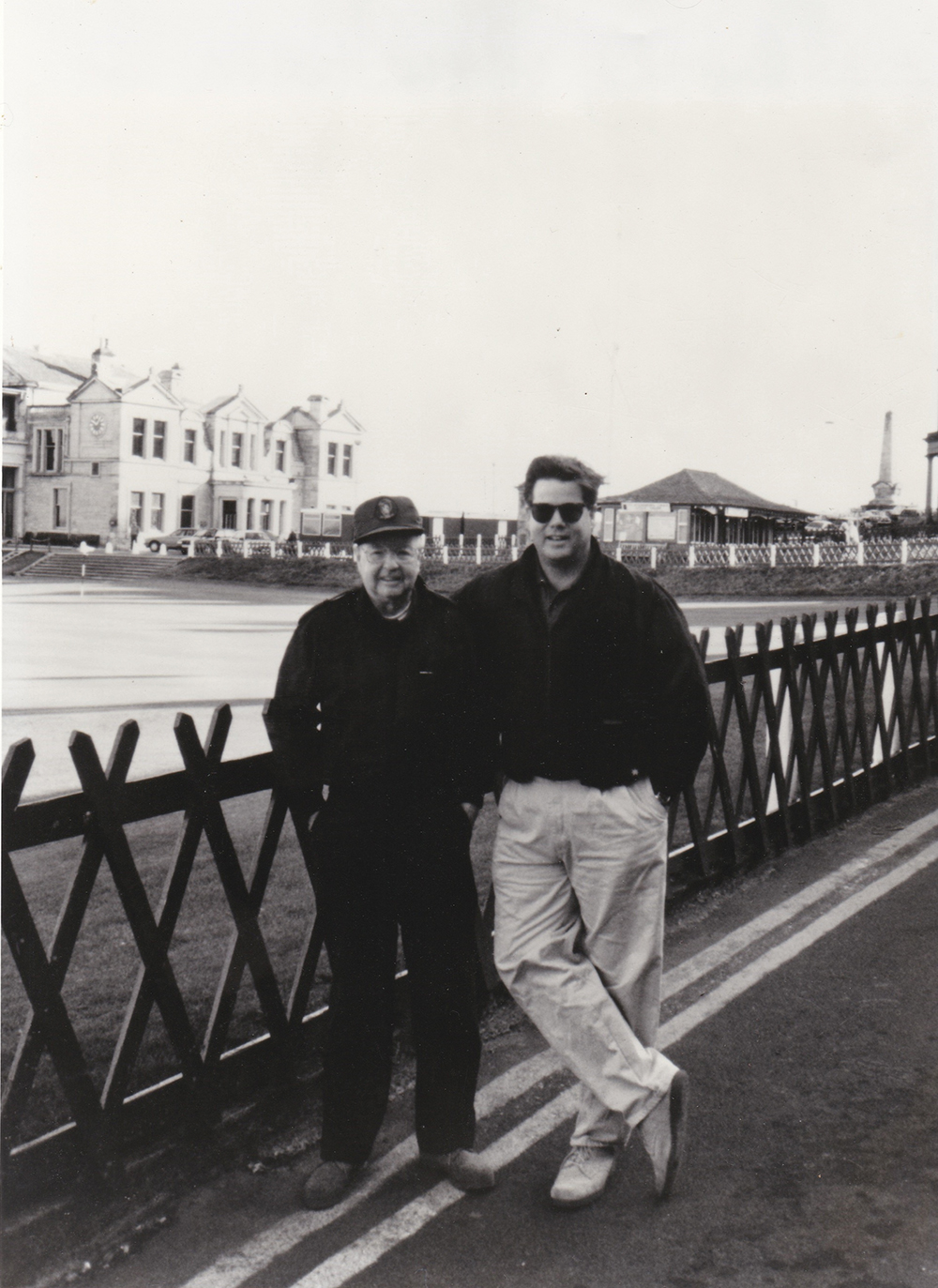

His son, my old man, Brax Dodson, was an ad man with a poet’s heart. He loved poetry, American history, good bourbon, golf with chums and everything about Christmas, not necessarily in that order. He sometimes smoked a beautiful briar pipe he brought home from the war and moderated a men’s Sunday school class for more than two decades. A man of great faith, he’d experienced unspeakable tragedy during his service in Europe but never spoke of it. Instead, he lived his life as if every day was a gift, always focusing on the positive, the most upbeat character I ever knew.

My nickname for him, in fact, was “Opti the Mystic,” owing to his unwavering goodwill and embarrassing habit of quoting long-dead sages and Roman philosophers when you least expected it, especially to my teenage dates. I never appreciated what a gift he gave me until I turned 30. Lord, how I miss that man.

Regardless of where you come down on the nature versus nurture debate, one doesn’t need to take a deep dive into Ancestry.com to understand that each of us owns pieces of the people who came before us. If we are lucky, the best parts of them live on in us.

Having reached an age where there are more years in the rearview than the road ahead, I take some comfort in suddenly noticing how much I really am like Opti and Walter, good men who lived through hard times—and even tragedy—but never lost their common touch or appreciation for life’s simple pleasures.

Like Walter, I dig flannel shirts with large pockets, church hymns, quiet afternoons in my garden and sitting beneath the evening trees watching birds feed and skies change. I miss going to early church on Sunday mornings. But nature is my temple, too. For the time being, that will suffice.

Like Opti, I have a thing for poetry, American history, good bourbon and golf with chums, even quotes by long-dead sages and Roman philosophers that never failed to embarrass my children when they were teenagers.

Just like my old man, I love everything about Christmas. Some gray afternoon this month, I’ll fire up one of his favorite briar pipes just for fun, a little ritual that makes me feel closer to the father I’m missing, my kindly ghost of Christmas Past.

There’s one more important way I connect with Walter and Opti, who were anything but grumpy old men.

Both had wise and spirited wives who shaped their thinking and made them better people. I have a wife like that, too. Maybe there’s hope for me yet.