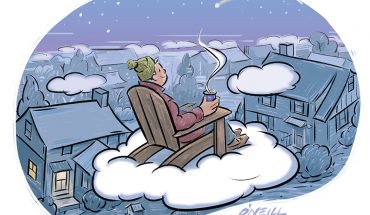

For this writer, it seems that the secret to the good life is that less is more

by Jim Dodson

A friend recently wondered why I named this column “Simple Life.” I joked that it was better than the original title I came up with — “Frankly, My Name Escapes Me.”

In truth, the name is as aspirational as it is functional, a useful reminder that the longer I live, the more I grow to appreciate the value of simplifying my life.

In a recent article, Simplicity: The Neglected Value, author and communications coach Bruna Martinuzzi points out that we time-enslaved, stressed-out, overworking humans simply don’t know what’s good for us when it comes to where we place our focus in life.

“We read and hear enough about its benefits in just about every facet of our lives,” she writes, “yet we walk past it, every day, in pursuit of the more complex, complicated, tangled, and sometimes puzzling. There is no glitter in simple, not enough buttons to play with. We fear that simple equates with easy, light, too basic — unsophisticated.”

Leonardo da Vinci, in fact, declared simplicity the ultimate form of sophistication. As did the likes of Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, Walt Whitman, Lao Tzu, Yogi Berra, Marcus Aurelius, Leo Tolstoy, and Maya Angelou. Rumi called it the dust that hides the gold.

Whether planning a wedding or a war, simplicity is key to a successful outcome, knowing what’s not essential and eliminating it before things get out of hand.

A year ago, the combination of the pandemic and wedding plans that had grown far more complicated than expected prompted my daughter, Maggie, and her fiancé, Nate, to postpone and rethink how they wished to tie the knot. They’ve since envisioned an intimate gathering of close friends and family to celebrate their union when the moment is right, somewhere in nature, stress-free, and away from the madding crowd.

One unexpected benefit of this strange year of distance and isolation, social scientists and trend-watchers report, is a broad refiguring of how we Americans live, work, and appropriate our time.

While churches and bars — the yin and yang of modern cultural society — still struggle to stay open, life-enriching activities like meditation, Zoom yoga, home gardening, golf, and bird-watching have mushroomed in popularity. According to more than one expert on the American work- place, mobile workspaces and home offices will be the engine that produces the next Industrial Revolution, spawning a vast new generation of home-grown entrepreneurs and inventive visionaries.

History holds some encouraging parallels. During the Great Depression and second World War, an era of severe economic dislocation and public self-sacrifice, a generation of self-made engineers, tinkerers, and inventors — many working in the isolation of their own garages and backyard sheds — managed to create everything from frozen foods to the first computers, color TV to dialysis machines, jet engines to Tupperware. That boom became the foundation for the consumer revolution and space age of the 1950s and ’60s. Your smartphone is the godchild of that time.

A couple years ago, while traveling the Great Wagon Road for my current book project about America’s original immigrant highway, I paid an afternoon call on a lovely Amish family, the Lapps, who live in the heart of Pennsylvania’s lush Lancaster County.

The “plain” ways of America’s Old Order Amish — such as their unadorned clothing, use of oil lamps instead of electricity, and reliance on horses for transportation and farming — are an echo of our vanished agrarian past and a living reminder of the virtues of simplicity.

Amish and Mennonite farmers were the first European settlers to answer William Penn’s call to Lancaster County in the late 17th century, using their wise farming practices and love of the land and their animals to transform the county’s rich limestone soil into the most productive farmland in the nation. The so-called “Garden Spot of the Nation” is now regarded as the birthplace of American agriculture.

The Lapp family’s ancestors had been on their land since before the American Revolution, living as comfortably in accord with nature and the Divine as anyone I’ve ever met. After Mervyn showed me around his immaculate barns, we sat with his wife, Catharine, in the evening light, sipping delicious meadow tea — a drink made from boiling fresh mint gathered from surrounding fields — beneath a grove of old trees. They talked about their three grown sons, all of whom worked in the family’s masonry business, and how devotion to God, family, and the pleasure of doing good work with their hands were the pillars of a rewarding life. It was one of the most pleasing interviews I’ve ever conducted.

For the record, there were even a few myth-busting surprises, including the fact that the Lapp men were all crazy about playing golf, and that Mervyn was a life-long L.A. Dodgers fan who often watched games on his neighbor’s television.

“If you’re smart,” he told me during our walk through his beautiful stone barn, “you take stock of what’s really important in your life… and other things you can simply live without.” He paused and gave me a wry look. “Simple things are always best. That’s a key to happiness. But I do need my Dodgers.”

As I drove home to North Carolina on a winding backcountry road, I was reminded of my own aspirations of simplicity, beginning with my chosen route home. Getting anywhere fast is one thing I can do without.

In his 1939 classic, The Importance of Living, Lin Yutang points out that beyond the noble art of getting things done, there may be an even nobler art of leaving things undone. “The wisdom of life,” he writes, “consists in the elimination of nonessentials.”

During this year of distance from friends and family, in place of going out to movies or dinner with friends, an older couple I know took up reading to each other every morning from their favorite books, a practice they plan to continue indefinitely. “It’s been a wonderful discovery,” Harry reports. “A simple gift that’s brought us closer than ever. It’s now part of our lives.”

Over this same interlude, I began work on a large garden I have dreamed of making for many years, one that will probably take me many more years to complete. As any gardener knows, of course, a garden is never finished, so my education as a man of the soil — and my wonder at its constant gifts — will never cease, until I do.

Simply put, what a lovely thought.

Jim Dodson is the New York Times bestselling author of Final Rounds: A Father, A Son, The Golf Journey Of A Lifetime. He lives in Greensboro.