For kids in the 1980s in Raleigh, play structures were pretty basic. But, this writer asks, were they really missing anything?

by Matthew Busch

Sitting on a plastic park bench, I watch my 3-year-old daughter play on a plush green cushioned pad in Pullen Park. She’s nonstop, but I get the sense that she could bounce off any of these surfaces unscathed. No scraped knees, no splinters from coarse hemp ropes, not one limb stuck, pinched or twisted. The choices at Pullen Park today are staggering compared to what they were in my youth.

I’m hunched over in my usual poor posture, shaking my head. You don’t realize how good you’ve got it, kid, I think to myself. With fingers laced in my lap, I’m rolling my thumbs. I chuckle to myself, feeling 40 going on 87.

The sun is setting by the time we’re ready to leave. I notice aspects of the park that haven’t changed since I was a kid: the train tracks, the deep-green foliage of trees, the shrubs creeping out, edging towards the pond. The comforting heat of summer when the sun’s rays are low. It’s magnificent.

Looking at the pond’s embankment triggers a memory. When my cousin was a child, we had a portrait taken of him on that very spot. I can see him sitting there, wedged in the liriope, laughing out at the water, with a cane pole in hand. I think of being a child again, and what Raleigh playgrounds were like in the 1980s.

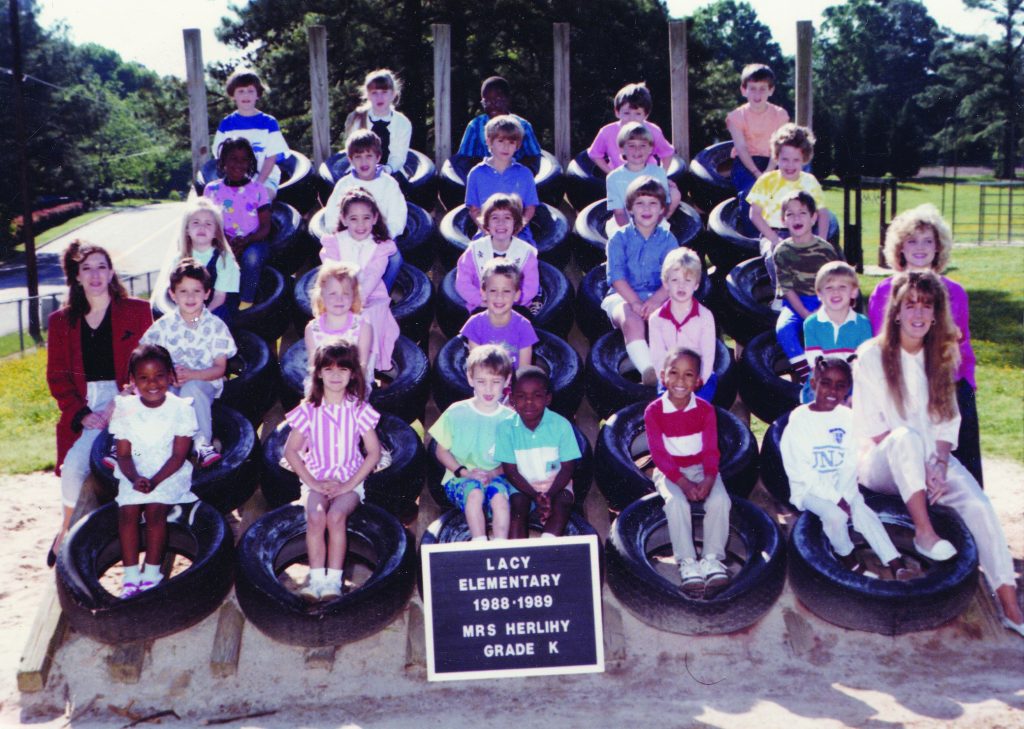

Short version: they were a blast. Back in my day, playgrounds resembled an Army basic training course, outfitted with simple materials like concrete, tires, sand and wood. At Lacy Elementary School, we had the tire ramp, a marvelous obstacle with six rows of giant tires nailed to wooden beams. It sat in an open field like a sundial, and by recess it was hot enough to fry an egg. An athletic kid, which I wasn’t, could have climbed it for exercise.

I preferred it as a perch to relax and bask in the sun. By mid-spring, when the weather was heating up, I’d tie a sweatshirt around my waist to protect my legs from the blazing black rubber, then lean back with my fingers laced behind my head to take in the Carolina blue skies.

And then there was the giant concrete pipe in the sand. By fourth grade, I knew that if I wanted to get romantic, its elegant coziness was unmatched. Palms flattened, I’d frantically sweep out all the sand, then recline, legs crossed, ready to welcome the first female passerby to join me: “Oh, did you want to get in here too? Come on in — I’ve just been sitting here gazing upon this lovely chewing gum fresco.”

And then they put in another concrete pipe right beside it. Kiss romance goodbye and bring on the game of war! Magnolias were our preferred weapons. The buds would drop along the fence line and we’d turn them into grenades, breaking off the little stems like firing pins. When the teacher wasn’t looking, we’d form teams and hurl them at makeshift targets.

Outside of school, the playground offerings were just as interesting and just as interpretive. Pullen Park playground offered psychedelic structures made of concrete: free-standing slices of Swiss cheese to climb for hours, dolphins and turtles rubbed smooth from years of children’s hands and feet. When we got hot, we’d climb onto the water fountains, feeling the bumpy texture of the yellow pea-gravel concrete, cool from the water pipes embedded inside.

A block over on North Carolina State University’s campus, the athletic fields were empty in the summer, which made them prime real estate for us. Here, we found giant green sports fields and sandpits full of molded concrete weightlifting equipment. We’d play shirts versus skins tag football, and by the end of the game the shirtless team would be itching from bug bites and grass scratches. Near the steaming red-rubberized track was a water jump pit for the steeplechase events; by summer the somewhat questionable water was filled with tadpoles for catching.

When the SAS All Children’s Playground opened in 1991, high-tech name met high-tech park. The wooden structure was all turns, staircases and bridges, something straight out of an M.C. Escher lithograph. There, we’d play “castle,” hoisting a triangular red flag up a pulley to the top of a steeple (earning splinters and rope burns in the meantime). But even this intricate playground left plenty of room for play, sparks for imagination.

Back to present-day: I look at my daughter’s face as she wildly climbs a synthetic-rope spider web. Her brow is scrunched down; she’s intensely focused as she makes it to the top and back down. As soon as she’s done, she’s on to yet another part of the park. No pause. All kinetic. It’s circuit training. It’s as if these attractions were created to maximize the exertion of energy. A nearby mom tells me they’ve opened a “ninja indoor playground” out past 540. Hmmm, I chuckle to myself, We’re raising ninjas.

As we gather our stuff to head to the car, I say out loud, “Nope, you don’t realize how good you had it, kid.” “What did you say, Daddy?” my daughter chirps. “Oh, nothing,” I respond. Today’s playgrounds seem safer, they have cooler features — but are they really any better? Back in the ‘80s, we may have had less, but we found deeply gratifying ways of making more.

This article originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.