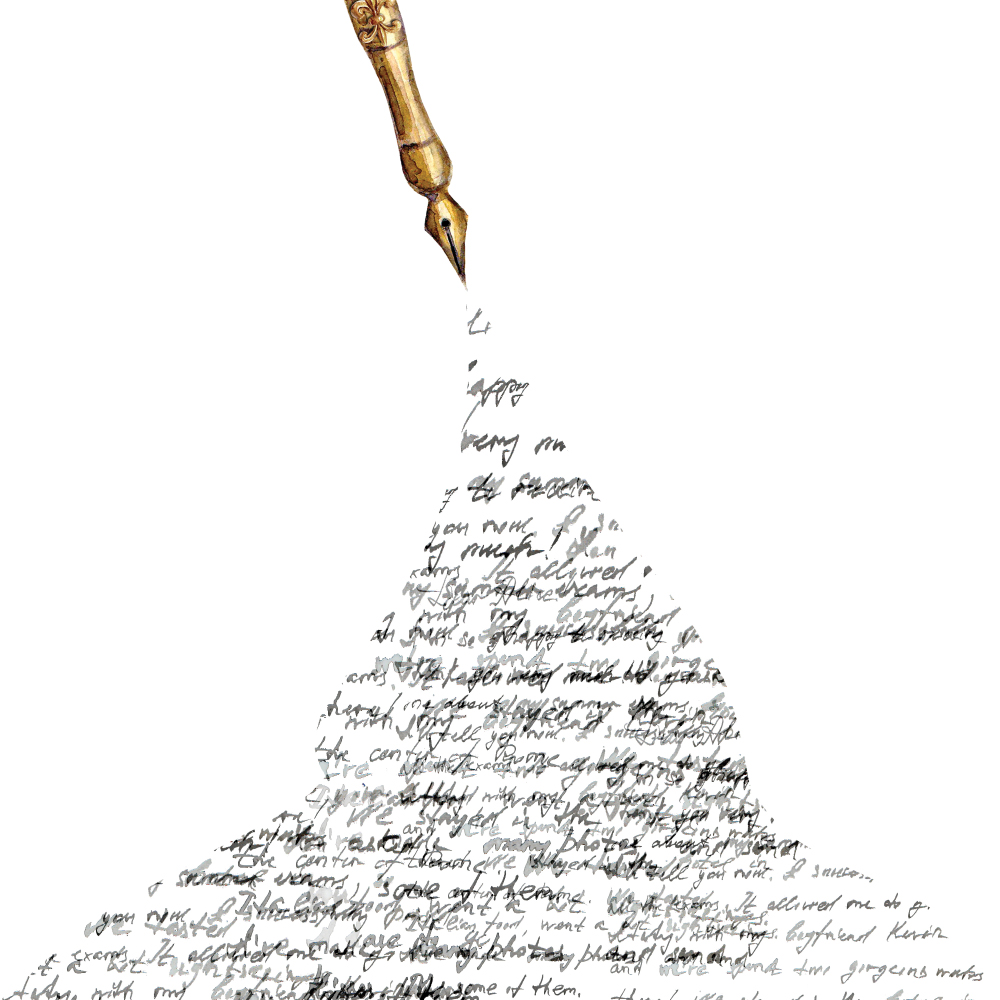

A poet pledges to write each day for 365 days, and finds that the exercise awakens a new creative energy.

by Gideon Young

Late November, 2021. Our children are playing “ice cream store” and “toy store” with pennies and nickels. They’re almost ready for their next denomination, and I’m thinking of ways to clean and sanitize. I write a short poem.

It doesn’t ring as pure as their laughter, nor is it as well-wrought as their arguments, but I write it and save it with an exclamation point. This small poem holds significance to me beyond its language or imagery: it marks my one-year anniversary of writing every day.

Over 12 months, I wrote poems, essays, and beginnings of essays. I wrote children’s books and ideas for educational books. I wrote in form: kwansabas, tanka, and contemporary haiku. Most of my writing throughout the year was haiku — full with seasonal words, dreaming room, a focus on nature, and perhaps surprisingly to some, no adherence to syllables.

I was not alone in this journey. My daughter, reading over my shoulder as I typed a few last lines before making breakfast, might say, “I like that, Dada.” More than once I revised a poem by singing them as goodnight songs to my son, more variations than perhaps he wanted to hear. My laptop was always on, the slowly lengthening file open. Perhaps it helped to have one large digital sheet of paper. No time was wasted with file names, or new beginnings.

old dimes

coming to a shine

at the bottom

of a glass jar

of dark cola

I had set aside creative writing as its own goal. Earlier in the year, during a critique meeting of the Carolina African American Writers’ Collective as we celebrated our 26th anniversary, members had discussed how marketing writing and creating writing are two different jobs. The brain cannot work on both at the same time. This shared wisdom helped me.

My stay-at-home dad schedule allows, on the most productive of days, two or three short opportunities for work. Like many of us, much of my work is composing and answering emails. Regularly, I also update a few websites, critique manuscripts, and collate submissions for publication. All of these actions include writing, but I chose to separate my yearly goal away from these business activities. Even during the three weeks I was writing four different Lexile level versions of my upcoming children’s book, I still wrote daily in my year-of-writing-file.

scrubbing sweet potatoes

soap and red clay swirl

in the sink

Much of my inspiration was life around me, but throughout the year, I discovered a few supportive practices that bloomed evergreen scents of inspiration and preservation. I welcomed natural cycles. In the beginning, my writing was full of Christmas lights, intergenerational moments of teaching, and mirth. In the spring I wrote about daffodils, the coldness of dirt, hope like reflected sunlight. When my grandmother died six days after her 104th birthday, all my writing breathed her life — her family’s midnight escape from Texas after Klan members burned their establishment; her completion of nursing school in California despite segregation preventing her from eating in the dining hall; how she and my grandfather, a medical doctor, birthed Black babies in Inkster and Belleville, Michigan. I still hear her voice.

hummingbird

inspects blue

wind chimes

Another practice was to focus on different forms of poetry. For a few weeks, I wrote kwansabas, which are African-American praise poems: seven lines, seven words in each line, no word more than seven letters. Then I focused on a different technical component of haiku each month: dreaming room, meeting the reader, juxtaposition. November was full of tanka, a five-line poem similar to haiku, with more narrative feel. I did not tie myself to judging improvement, only to the idea of practicing.

holding the mug

from Great Grandma

with both hands

Not every day contained gold. Many days I knew the poem I was writing was trite, the dream boringly vague, the idea undefined. There was a freedom I found in practice: not everything needed to be publishable. I embraced the raw side of my writing. Sometimes, as I was writing, I would say aloud, “This isn’t very good.” But this unpolished writing ended up serving two purposes: to remind me of the true goal, and to write.

Before this year of writing, when I would sit down to create — which was not nearly as often as I wanted — I contained a stifling pressure to “write something superb” or reach an epiphany. I was not partitioning business from creation. I was trying to make something from nothing.

heliocentric

dear child, our sun does not rise.

when the sun is hidden under earth,

has not yet drawn itself as whole

note on the rough line of horizon,

know we are in its eternal view.

to the Sun, earth and humans are

just one speck of light coming home.

I believe in the energetic powers of humans, that those things upon which a person focuses their time, thoughts, and actions, are given strength to grow in their life. I did not enter into this journey with any business goals.

I feel lucky to have had my most “successful” year of writing this past year — a debut haiku collection, two forthcoming books for young readers, a commissioned multimedia literacies film, and multiple award nominations. I attribute these outcomes directly to the long-term energy produced by daily creative work.

I have finished a year of writing every day. Now what? I learned early on that I have found a new way of life that mirrors the shifting shapes of light in my soul. Having finished a year of writing, I am already amid the next.

_____

This article originally appeared in the January 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine