A trip abroad reminds this writer’s of the night sky — and that the trees and songbirds in his yard back home are precious and worth preserving.

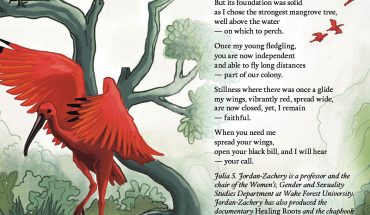

by Jim Dodson | illustration by Gerry O’Neill

During a business trip to a remote part of New Zealand last winter, I was reminded of the staggering beauty of the night. Stepping out of my bungalow just after midnight, the stars of the Southern Hemisphere took my breath away. There were millions of them arching overhead, blazing like white diamonds on black velvet.

Because it was summer down under, there were also vivid sounds of calling night birds and insects murmuring in the fields and forests around me. I sat down on a wooden rocking chair and just listened for the better part of an hour, a perfect bedtime lullaby that reminded me of my daily wake-up routine back home in North Carolina.

Well before sunrise most days, I take my coffee outside to sit beneath a grove of old trees and wait for the first songbird to herald the breaking day. Save for an occasional passing train or distant siren that briefly mars the silence, it’s the stillest part of any day, the perfect moment to think, meditate, pray or just be.

I’ve captured the first birdsong many times on my handy Cornell Lab Merlin Bird app. In my neck of the suburban woods, it’s usually a Carolina wren or eastern towhee that breaks the predawn serenity. Sometimes it’s the northern cardinal or melodious song sparrow that takes a lead solo. Every now and then, a great horned owl or brown thrasher cues the chorus.

Whichever one starts, as sure as night is dark, a chorus of a dozen or more birds soon join the songfest, including gray catbirds, mourning doves and American crows.

I never tire of this avian awakening, finding a sense of true gratitude for my tiny spot on Earth as a new day begins.

And yet, I worry.

Last year, a report from National Audubon noted that the U.S. and Canada have lost 3 billion birds over the past half-century, and that half of America’s bird populations are in decline. More than one expert warned that we are already in the early throes of the Earth’s sixth mass extinction.

Global warming, loss of natural habitat, various forms of pollution and the fact that the night is no longer as dark as it used be are cited as primary contributing factors to the decline of thousands of species of birds, insects, reptiles and mammals, roughly half of which hunt, mate, feed and travel by night. Disappearing forests accelerate this decline.

So what is an ordinary, suburban nature-lover and bird nut to do? That depends, I suppose, how you grew up. I sometimes joke that I grew up in darkness.

I had the privilege to grow up in a succession of sleepy Southern towns, following my dad’s itinerant newspaper career. From the coast of Mississippi to the Carolinas, with an imagination fired by nature, I explored woods and creeks, bringing home frogs and injured birds.

The rule was I had to be home by “full” darkness. Many an evening, I lingered in the twilight just to watch the fireflies come out and listen for the sounds of crickets, bullfrogs and night birds. In those days, the streetlights in these quiet rural towns were few.

I’m not speaking, mind you, of the metaphorical darkness showcased by everything from the Bible’s rich imagery of light and darkness (good and evil) to modern cable TV’s endless news loops of crime and disaster. There’s a good reason why depression is called a “dark night of the soul.” Anyone who has experienced it might be forgiven for believing that the world is coming apart at the seams.

Thirty years ago, in an effort to give our children the benefits of a quieter, natural world, my wife and I built our house on a coastal Maine hilltop surrounded by a dense forest of beech and hemlock, where the nights were deep and woods teemed with animal life.

The first thing I did when we moved back to my hometown neighborhood seven years ago was plant 20 trees around the property. Today in summer, our house sits in a grove of beautiful trees. In our neighborhood, giant oaks, maples and poplar trees arch like druid elders throughout.

These trees provide home to a rich variety of birds and insects. They also give us welcome shade in summer and showcase the stars on winter nights.

Turning down the lights at night strikes me as one small but sensible act of kindness to nature, encouraging the living world around us to rest so moths and other nighttime creatures can pollinate plants, fertilizing the start of the world’s food chain.

In her lovely spiritual memoir Learning to Walk in the Dark, theologian Barbara Brown Taylor points out that most of the monsters we fear in the dark are simply phantoms we create in our anxious, sleep-deprived minds.

“I have learned things in the dark that I could never have learned in the light,” she writes. “Things that have saved my life over and over again, so that there is really only one logical conclusion. I need darkness as much as I need light.”

I was reminded of this fact one morning at summer’s beginning while awaiting my woodland wake-up call. Savoring the predawn stillness beneath the trees, I suddenly realized that the fireflies had returned, magical messengers of hope that would be nowhere without the night.

As August passes over us and the days grow shorter, the darkness grows.

I say, bring it on, dear neighbors, and sleep well.

This article originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.