A Rockingham county writer shares this short fiction story about a women who finds herself in a curious house with a mind of its own.

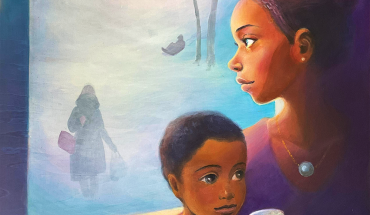

by Valerie Nieman | illustration by Jenn Hales

Andi hadn’t been startled awake for several nights, ever since the contractor fixed that foundation problem, but now she sat straight up in bed. Something was wrong. The house, her new home in a new city, remained quiet, all that groaning and cracking having been eliminated by the repairs.

It was that other silence — no hum of cars passing on the street, no sounds of a city waking up. And, she realized as she stared into total darkness, no streetlight glow filtering around the blinds.

For a while, she heard nothing. Gradually, light began to show and she heard a chorus of shrieks and whistles — birds? She got up, shuffled to the back door and opened it on a bright dawn, cornfields stretching flat and green in every direction.

The rows came right to her steps, tassels waving well above her head. Blackbirds wheeled in huge flocks.

Her house had moved. And she had moved with it.

Even as she tried to make sense of it, speculating that this looked like Iowa — must be, maybe, everyday, common Iowa, nothing to be afraid of — the rest of her brain was rabbiting around the bonkers impossibility of her situation.

*

She had loved the cottage from the moment the realtor opened the door, but, after moving in, she came to realize there was an uneasiness about it. Day and night, floors creaked and popped without the weight of a footstep.

When she reached to put something in a high cupboard, the top of it did not line up with the ceiling. Everything was slightly off one way or another, but that’s the way old houses were. They settled year by year, in a long, uneven conversation with the ground.

She didn’t miss her previous home. It wasn’t that, at all. When her ex abruptly went away (for good this time), and shortly after so did her job, she’d decided she needed something smaller to meet her changed circumstances. Something older, solid, with its own history.

Stay, or go. It hadn’t been a difficult choice. Her former home had no longer felt like home. It just felt like him, his house, cold all the time.

*

Three different construction dates — 1921, 1927, 1928 — were listed variously on deeds, descriptions, and reports. It made no sense. A house was completed or not in a certain year. The cedar-shake cottage had been moved sometime in the 1970s and new sections had been added, a porch, a deck. Extensions that almost seemed to buttress the square main building, pushing out on three sides.

Andi had become fascinated by the idea of house-moving. It wasn’t unusual, of course; houses were moved out of the path of development all the time. Even lighthouses were raised up on rollers and carried inland, away from the encroaching sea. She remembered reading about a town in Minnesota that was hauled away from mining damage by horses and tractors and a steam engine. Elsewhere in North Carolina, the former village of Avalon had been moved when its mill burned down, the little houses incorporated into the neighboring textile town of Mayodan.

History was like that, for a house or a person — gaps in the record, mysteries.

*

The recommended contractor came within a week — the benefit of a small town, Andi supposed — and rang the doorbell with his ball cap off, gripped in his hands like he was entering a church.

“Miss Andrea?”

“Andi.”

“Miss Andi. I am pleased to meet you.” He paused and glanced inside. “What were you needing done?”

“I’d like you to look at the foundation.” It sounded too — something— to say she heard strange noises. “I understand the house was moved. Is it well supported? The home inspector didn’t mention anything.”

“Well, you are spot on about the move. I remember when they did it. Quite the show, with traffic held up and all. They put an office building where it used to be.”

He kept talking as she led him back to the utility room and the trap door to the crawl space, wondering if a man that old (he had only a fringe of white hair around a polished dome) was agile enough to get around under the joists. But she needn’t have worried — he was quickly out of sight, banging around beneath the floor, and it wasn’t long until he came up out of the hole.

“Found your problem.” He turned off his flashlight, dusted off his hands. “The main support beam, a steel beam at that, has been cut in two.”

“What?” That sounded terrifying, as if the house might bend at the center like a cardboard box and fold itself flat.

“Yep. Might have been part of moving it, I don’t know.” “Is it dangerous?”

“No, no, there’s plenty of support pillars. Just… strange.” She hadn’t been able get the vision of a collapse out of her mind. “Can you put it back together?”

“I can do that, sure. Have to come back with some tools, bolts and such. And good steel.”

And so it was done.

*

Two mornings after the cornfields appeared, she awoke to the mooing of cows.

She hadn’t ventured into the tall corn, featureless as a sea. Now she looked out on new fields that rolled away over little hills, fields bounded by hedges instead of fences. Brown and white cows. She looked out of windows on each side of the house. Far away she could see a steeple and what appeared to be a castle.

England?

The house did not move on a regular schedule. It stayed in the same place for days, even weeks, then she would hear the wind moaning from a new corner of the eaves and look outside to see — what was that?

She was cautious. When the house set down in a populated area, no one seemed to notice. People apparently could not see the house, but once she stepped off the porch, they could see her. The first time she’d tried, somewhere under a hot, pale sky, black-haired children clamored at her and she ran back inside. They stood for a moment, wide-eyed, letting the stones drop from their hands, and fled.

Did she appear suddenly, popping into view? Was she floating in a bubble like Glinda? No way to tell.

The movement of the house in space and time became wider and wilder. One day she might look out on a Japanese seaside town with little boats and a pagoda, and a couple days later, she’d be in the United States, far to the north, in a logging town at the edge of a redwood forest. The house, severed from a permanent base, had no utilities, but Andi did have a large supply of candles. And a rain barrel that had been strapped to one of the additions.

I am resourceful, she thought. I am doing fine.

*

Turn and turn and turn again.

The days were long and the nights longer in the wandering house. She missed her friends, especially Nicole, a coworker who had stayed close through both the divorce and her early (forced) retirement from their employer. Nicole had always teased her for overly careful preparation, cautious decision-making. What would she say about this?

Andi even sort of missed her ex. He had been a familiar problem, at least.

She learned how to gather food in exotic places, covering her foreignness with a long, hooded cloak, a souvenir of her role in a college Shakespeare production. Where there was a store, a souk, a market cross, she waited and watched, moving in when the crowds had thinned and the leavings were cheap. The smell of cooked meat made her ravenous.

She could barter jewelry and small items to merchants. Gestures were pretty much universal. As her hair grew unruly and her scrupulously kept-up color faded to salt-and-pepper, with her head down and a hand upturned, she could sometimes gather alms from passersby. No need to speak. Maybe she couldn’t any longer.

*

Andi fell asleep with the house settled someplace that was high and cold and empty, a steppe. She woke to find it beside a long lake clasped by dark-forested mountains. Well down the shore was a cluster of thatch-roofed cottages.

Hunger drove her to the village and, as she looked for some place to get food, she was relieved to realize the people were speaking a sort of English. It wasn’t market day, but a house displayed a bush over the door. That meant beer was available, she remembered from a long-ago advertising class.

She nodded to the woman inside, dressed in a bodice and full skirts, her hair covered.

“Beer,” she ventured.

The woman, stout as one of her casks, looked oddly at her.

“Ale?” Andi mimed drinking.

The woman responded by shaking a bucket at her. Ah. Medieval takeout. She had no pitcher, bucket, anything with which to carry the beer away.

Andi put her hand on a pottery pitcher and indicated that she would buy it. She produced a piece of jewelry she’d brought to trade, an alloy ring decorated with the figure of a nude dancing woman.

The woman backed away, eyes wide, and whispered something that sounded like “elf.” Or “help.”

A man came from outside and she pointed to the ring where it lay. He picked it up and turned it in his dirt-caked fingers, squinted at her, and then spoke to the woman, who hustled off to get someone, a priest, a soldier, someone that Andi didn’t think she should meet.

She gathered up the skirts of her cloak and ran.

*

The house didn’t move that night, or the next, or the next. She wished it would.

Andi did not go back to the village, fearing people who feared her. Andi imagined the townspeople might think she was something supernatural, in league with the Devil. She also considered that maybe the stylized figure of a naked woman on the ring had offended them. People went past the house, on their way to fields or driving herds of sheep along, without even a glance.

Then a man as dark as a devil stopped right in front, turned and stared into the window.

“I spy a lass, through the window,” he said.

She hid behind the curtain.

“There thou be, though how this house came hither I dinnae ken.” The man began to walk away, and she thought he’d gone until he emerged from the other side, having circled the house. He stepped up onto the porch and came to the door.

“How can you see this house?” she asked, almost whispering into the gap between the old door and the frame.

“Metal calls to me, shaped in some cantrip-time.”

Andi opened the door but stood behind the screen as though that bit of protection would be sufficient to keep out this brawny man. A blacksmith, she realized, his skin and clothing darkened by the smoke of the forge.

“The house moves,” she confided. “It was cut apart underneath and then, when it was fixed, it began moving.”

He cocked his head as he listened, the way a dog turns its head as it tries to tune in its person’s unfamiliar words. “The house is magiked.”

She nodded.

“Gie me leave then to see?”

Andi opened the flimsy door and stood back. The whiff of fire and charcoal came with him. He looked around the room, bemused (What did he make of the black slab of the television, photographs on the wall?) then followed her to the access. Like the old contractor, he moved with the assurance of someone who dealt with problems all the time, physical problems that could be addressed with tools and skill.

He was quickly back up, head and shoulders out of the trap door. He tried to explain the situation, and now she was the one who couldn’t put all the words together. However, she came to understand that he had found the steel beam bridged by the contractor’s plates and bolts. “Can you fix it?” “Fixt? Your house is scarcely that,” he said, a smile opening his sooty face. “I’ve a gift from the Fair Folk to forge steel that will nae break nor blunt at the bite. Aye, I can do this task. A wandering heart can be put aright, house or lass alike.”

He heaved himself out of the crawl space. She pulled back, away from his seared hands and leather apron.

“If you do, if you fix — unmend — it, what will happen?”

“The heart was cut in twain to end the wandering. If I take away the clampar, ’twill rest again.”

She thought about the various recorded dates of the house’s construction. Had it skipped from year to year, somehow, appearing and disappearing until it was tamed?

“But where? Where will it be?”

“Why, here, lass! I canna make it skip the sea from one shore to another like a stane from the hand of the giant Benandonner,” he said, laughing. “Here this house stays, and thou with it, or else be ever a-wandering like Will-o’-the-wisp.”

She looked out at the dense forests and the long silvery lake. She was aware of the interest in his merry eyes. And the able heft of the man. Solid, he was.

“My folk will thee like. There’s much eerie hereabouts, m’self not least, though we’ve never seen a lass sa conveyed.”

He offered his fire-marked hand.

“Andi,” she said, as she took it.

A former professor at NC A&T State University and editor for the News & Record, Valerie Nieman lives and writes in Rockingham County. Her novel, In the Lonely Backwater, won the Sir Walter Raleigh Award for 2022.

This article originally appeared in the August issue of WALTER magazine.