From passionate to mundane, these romantic notes from decades ago offer a window into relationships then and now.

by Susanna Klingenberg

Real love is passionate, messy and mundane. And while today’s love notes are most likely sent through email or text — those Xs and Os becoming 0s and 1s — those of decades ago were sent on paper, a medium at once both fragile and enduring. Reading other people’s love letters may sound voyeuristic, but time works magic.

Reading historic love letters doesn’t feel intrusive; it’s heart-expanding, spirit-affirming and delightful. “It’s a common ground to connect with those in the past,” says Lauren McCoy, digital archivist at the North Carolina State Archives.

Over the next few pages, you’ll find a sampling of love letters housed at our State Archives. These letters are a sampling of the more than 100 million individual items in the archives that were submitted voluntarily by North Carolina citizens.

Together, they offer a snapshot of how they expressed love in words over the past 175 years or so. “The recipients of these letters found them to be so meaningful that they held onto them for years, even decades,” says outreach archivist Brooke Csuka at the State Archives.

Despite the occasional flowery language and old-fashioned writing, these sentiments are still buzzing with life. “Reading these letters, we see that people before us experienced the ups and downs of young love and the heartache and sacrifice of enduring relationships,” says McCoy.

As the years march on and the mediums change, the cadence of the human heart remains a throughline: we desire, we revel, we share, we squabble, we make up. We navigate life and love together, past and present. “These letters are preserved in perpetuity as evidence that true love lasts a lifetime — or maybe even longer,” says Csuka.

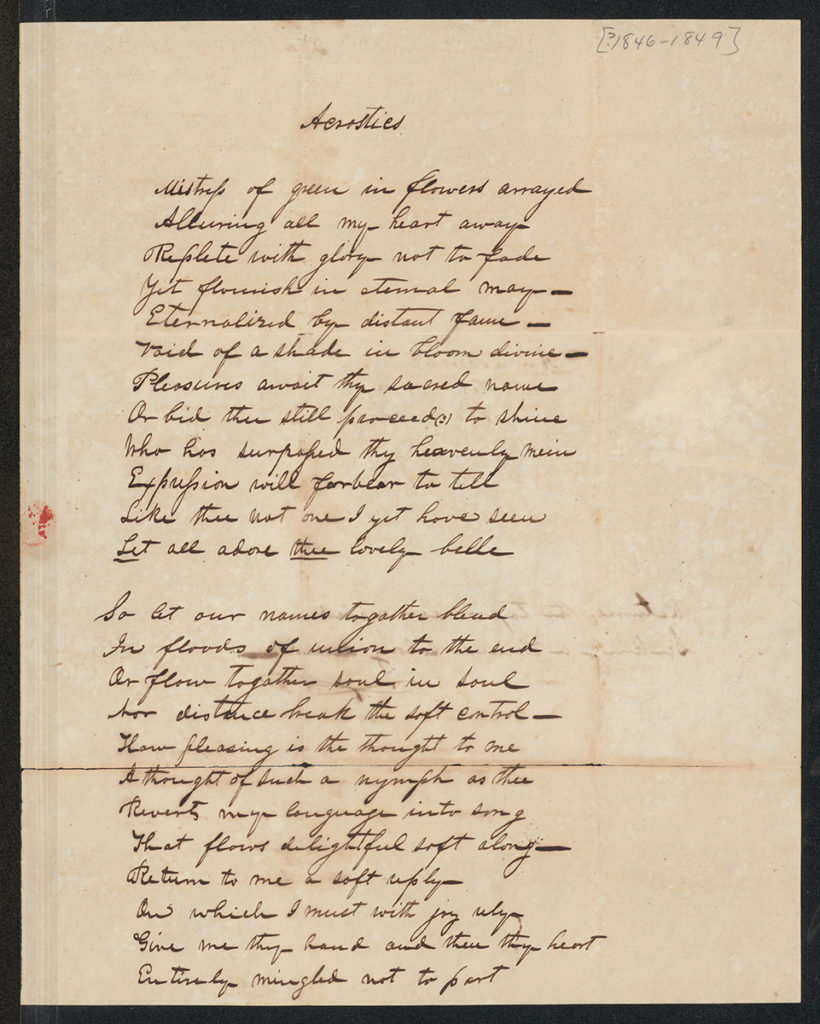

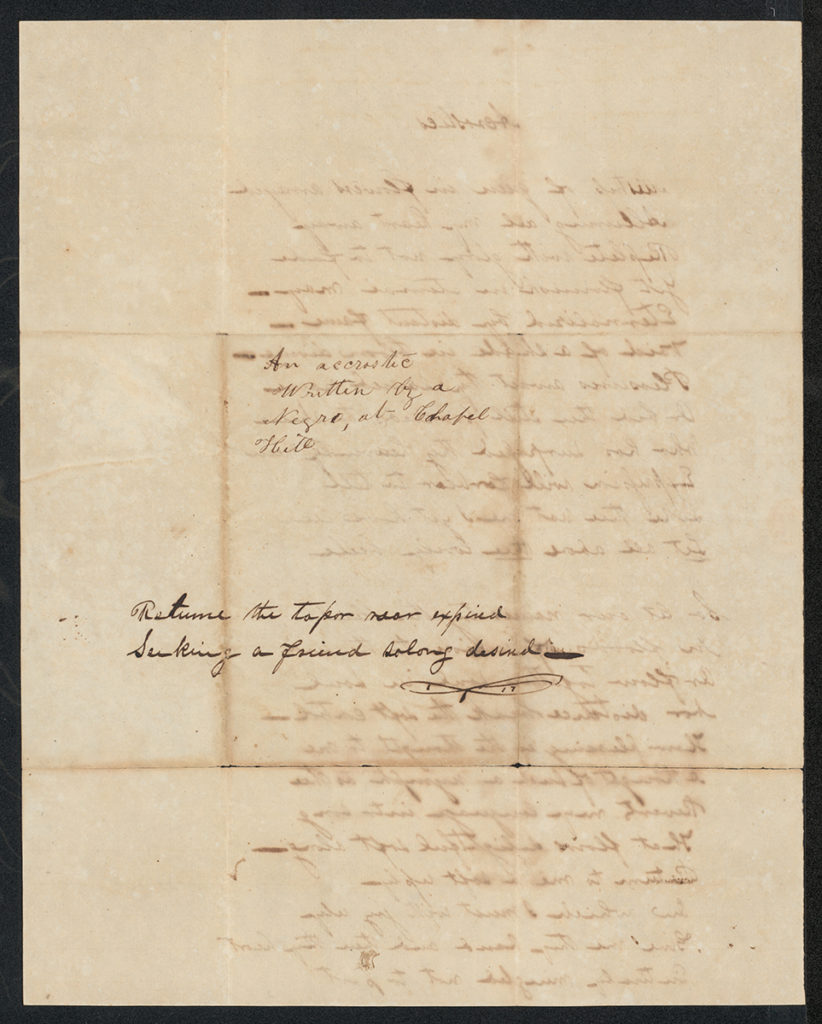

“Glory Not To Fade” (1846)

George Moses Horton, commissioned by Sion Hart Rogers for Mary Elizabeth Powell

George Moses Horton was a talented, mostly self-taught writer and the first Black man to publish a book in the South — an 1829 book of poetry called The Hope of Liberty. He was also an enslaved person who worked on the Horton family plantation in Chatham County.

The proceeds from George Moses Horton’s book were meant to buy his freedom, and historians are unclear about why that never came to pass. But he found other ways to earn money with his words. On weekends, he was sent to peddle produce from the plantation around Chapel Hill, and while he was there, he sold acrostic poems to students on University of North Carolina campus.

It was on one of those visits that a student named Sion Hart Rogers, a Wake County native, commissioned this acrostic for his sweetheart, Mary Elizabeth V. Powell. Powell didn’t end up with Rogers, but she kept the poem until her death, no doubt savoring the memory and the poetry of the language. “Mistress of green in flowers arrayed / Alluring all my heart away / Replete with glory not to fade / Yet flourish in eternal May…”

Horton remained enslaved until the news of the Emancipation Proclamation hit North Carolina in 1865. He was posthumously inducted into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame in 1996 and named the Historic Poet Laureate of Chatham County in 1997, among many other honors.

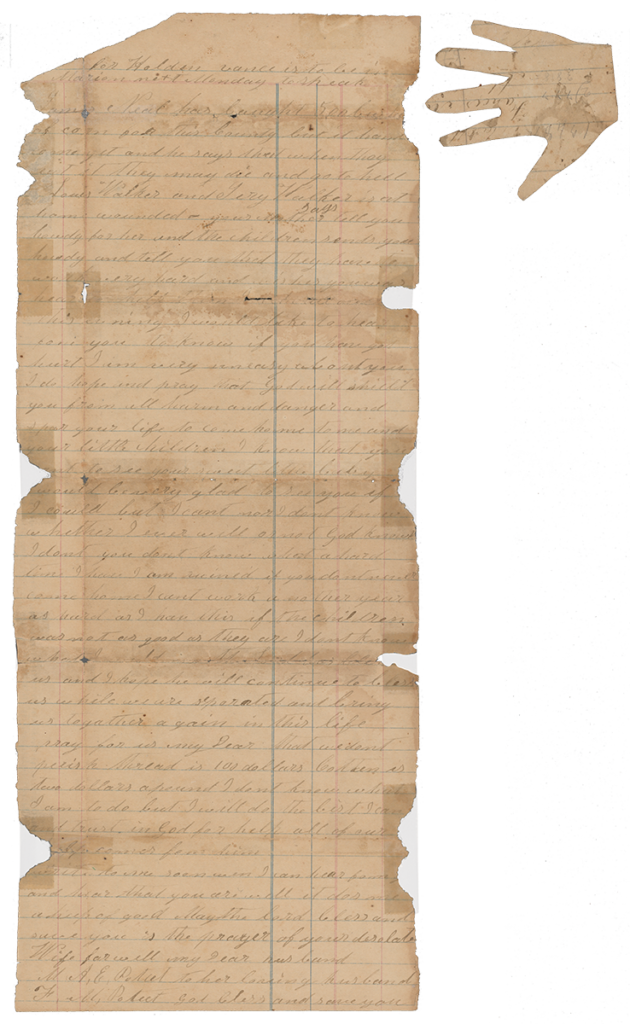

“Your Sweet Little Baby” (1864)

Martha Poteet to Francis Poteet

This artifact from 1864 will resonate with modern lovers: It’s from a busy woman who prioritized connection, perhaps over chores or sleep. While Francis Poteet was off fighting in the Confederate Army, his wife Martha managed their farm and cared for their children. Her letters to him were tender, but also showed strain; she was overwhelmed by single-parent life.

One letter laments, “I don’t see what on earth we will do — there ain’t corn to do the harvest, and the wheat don’t look like it will be any account.” Her notes always ended with a prayer for peace, so her husband could return, help on the farm and be with his children.

Nevertheless, affection and creativity prevailed. When a new daughter was born, Martha wrote a letter asking what to name the baby. Knowing her husband would be longing to connect with the daughter he could not yet meet, Martha cut a tracing of the baby’s hand and tucked it in with the letter. Francis kept the memento with him until the Civil War ended and he returned home.

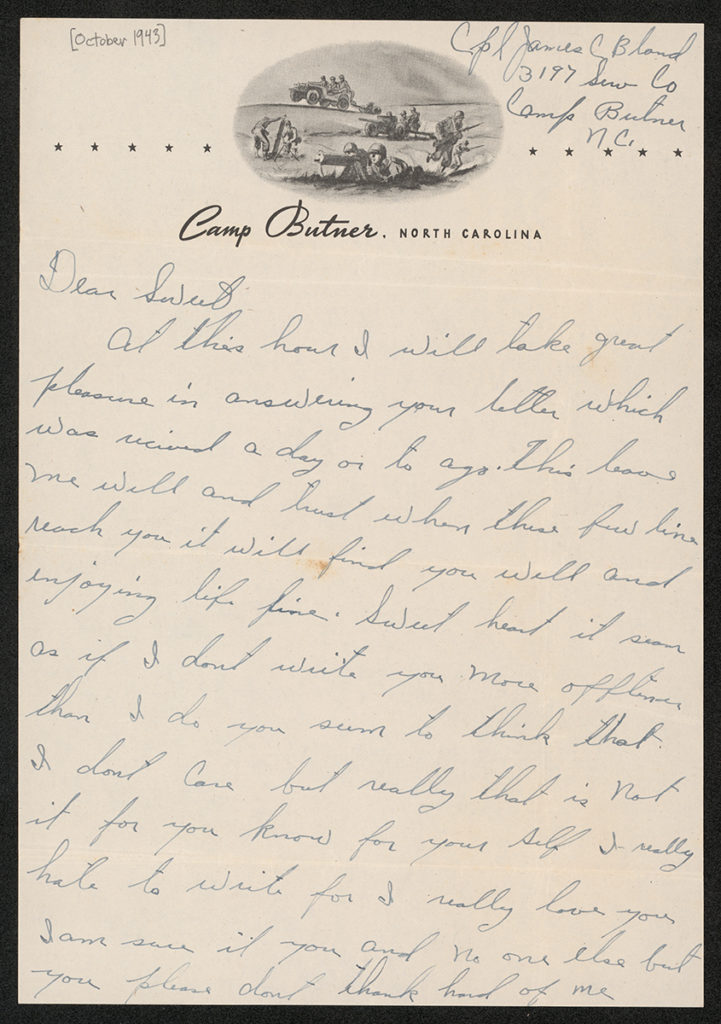

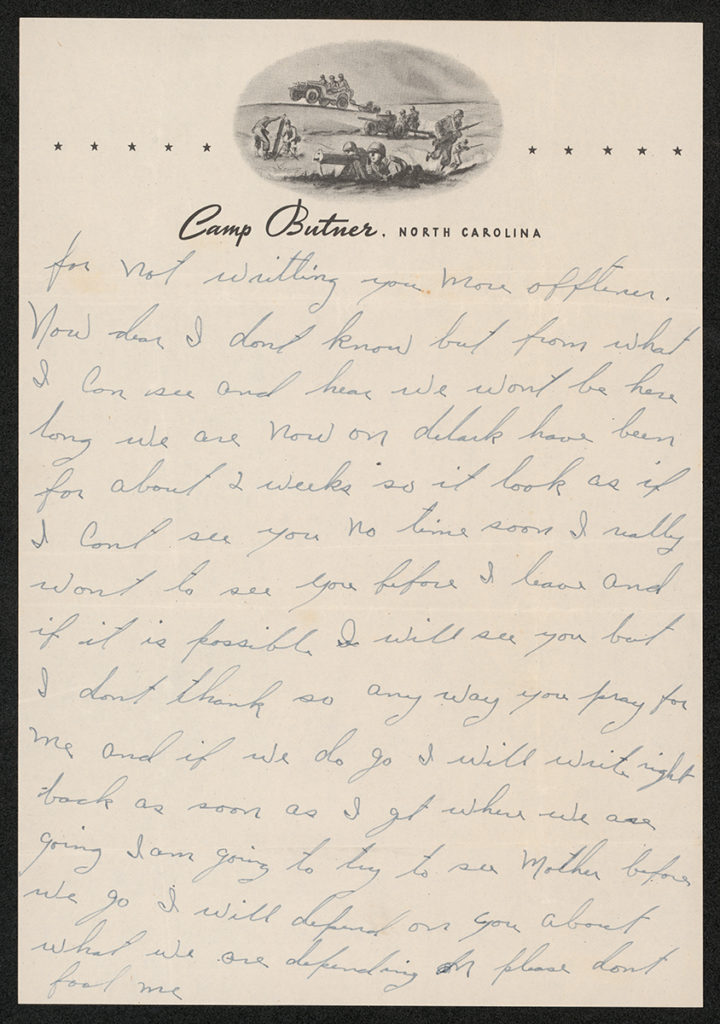

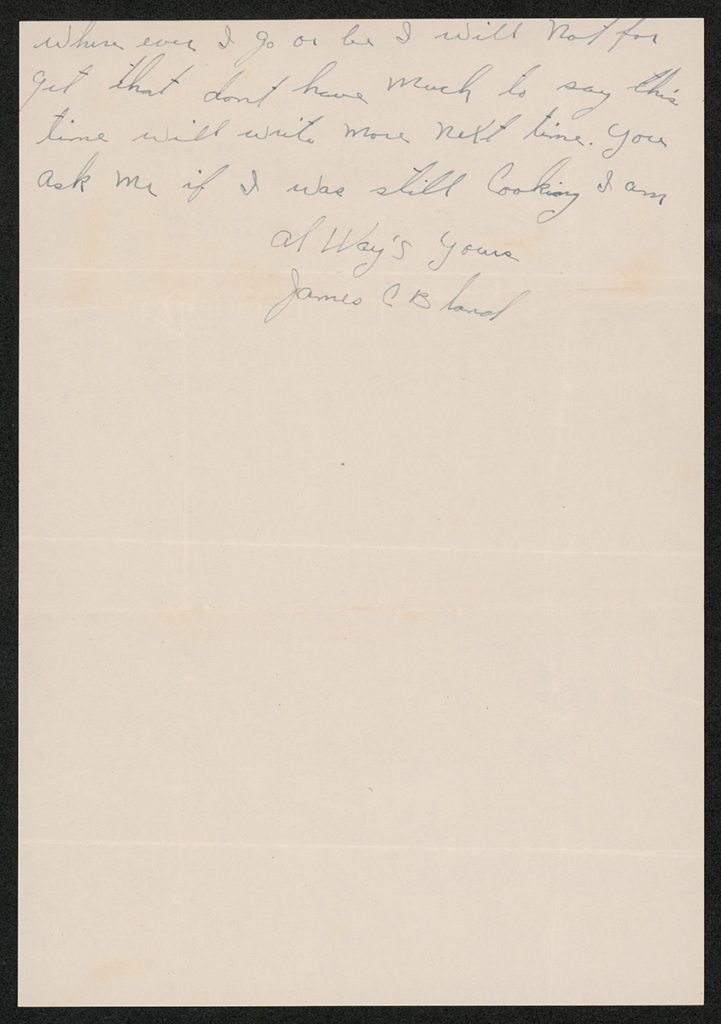

“Don’t Think Hard On Me” (1943)

James C. Bland to Margaret Richardson

Long-distance love is notoriously tough, and this letter is a glimpse into the emotional work of maintaining a relationship across the miles. James C. Bland and his then-sweetheart Margaret Richardson were both from Wake County. He served in World War II at Camp Sutton and Camp Butner before being shipped overseas to England in February of 1944. He begins his letter with a sweet opening and good wishes, but then he addresses what must have been a sore spot between them: how often he writes. “Sweet heart, it seems as if I don’t write you more often than I do, you seem to think I don’t care. But really that is not it. For you know for yourself… that I really love you.” What did Margaret say that put James on the defensive? Whatever it was, they must have worked through it, as the two were married when he returned from England.

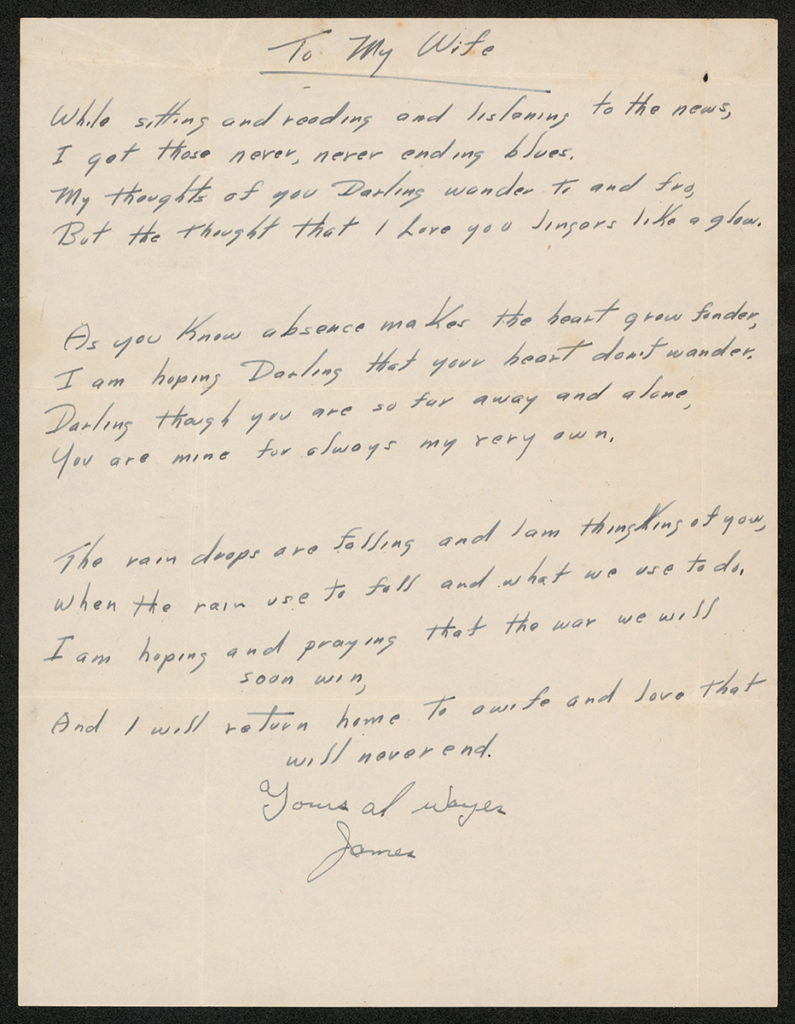

“Your Heart Don’t Wander” (c. 1947)

James C. Bland to Margaret Richardson

There’s something about the vulnerability of a love poem that melts the reader a bit. In this poem, which James may have written in anticipation of his wedding, he calls on some classic rhetorical moves by using light imagery, nodding to a romantic memory and looking forward to the future with hope: “The raindrops are falling and I am thinking of you / When the rain used to fall and what we used to do. / I am hoping and praying that the war we will soon win, / and I will return home to a wife and a love that will never end.” The deep creases in the paper show it’s been read and reread, and the sign-off at the end softens any awkward rhymes into earnest affection.

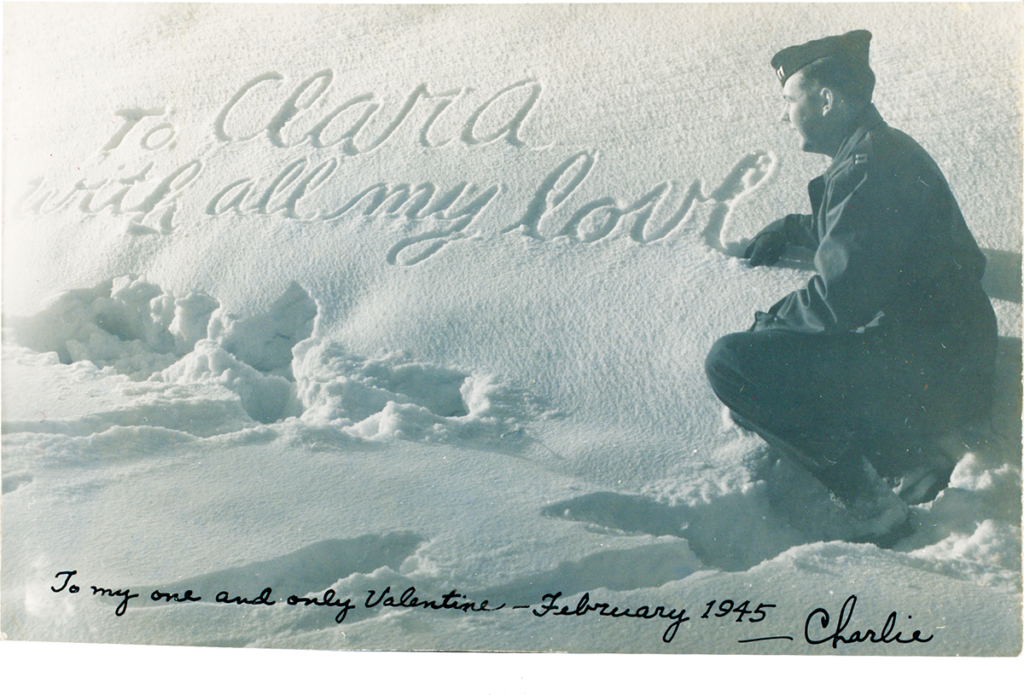

“To My One And Only” (1945)

Charles M. Allen to Clara Allen

A picture can be worth a thousand words — and it’s definitely worth a few chilly fingers. Stationed in Europe with the Air Force during World War II, 2nd Lt. Charles M. Allen Jr. of Mount Gilead wrote a Valentine’s Day sentiment in the snow for his wife, Clara. Part of the fun here is imagining Charles asking a fellow airman to conspire with him on the project: scheming the note, scouting out fresh patches of snow and snapping pictures for each other to send home to their loves. Did another soldier happen upon the note in the snow and copy his creativity? Did his buddy take the picture too early, before Charles looked at the camera? We’ll never know. But it’s a safe bet that Clara didn’t care one bit: Charles (Charlie, to Clara) remembered her across the ocean on Valentine’s Day, with a side of ingenuity, to boot.

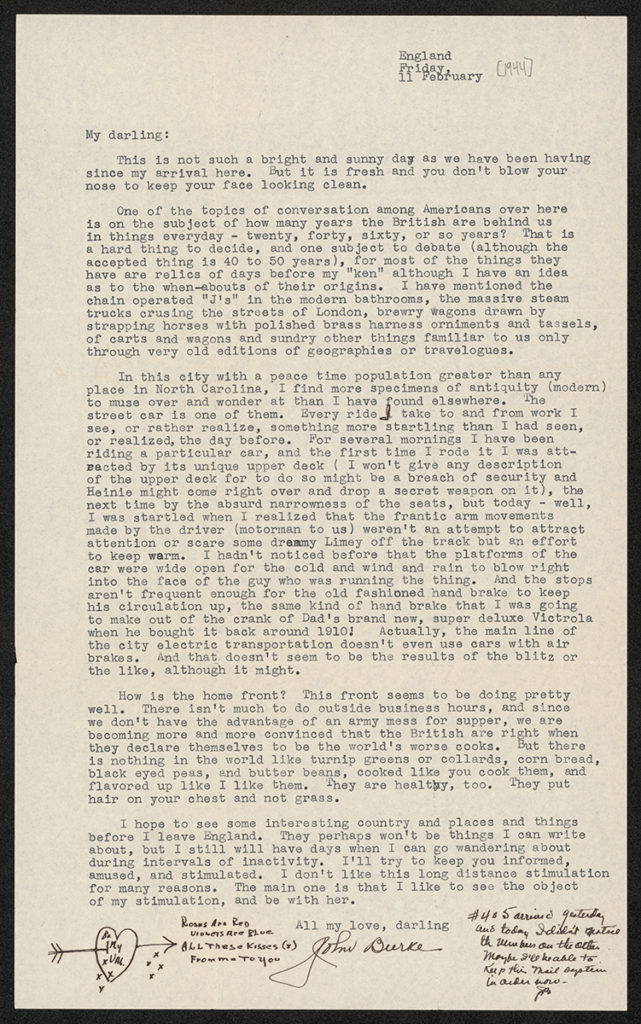

“The World’s Worst Cooks” (1944)

John O’Donnell to Leah O’Donnell

Captain John O’Donnell served in the Army Transportation Corps during World War II. He regularly wrote letters to his wife, Leah, but this particular one is as much a love letter to North Carolina as it is to his “darling.” He misses cornbread, turnip greens and collards, “cooked like you cook them and flavored up like I like them.” And he clearly thinks his home state could teach the Brits a thing or two about food — “we are becoming more and more convinced that the British are right when they declare themselves the world’s worst cooks” — and about technology, too. The letter reads like conversation over dinner — a mundane part of a relationship that soldiers must miss when they are deployed. The most charming touch on this one is the correspondence numbering system at the bottom, implying they both reread the letters and want them to be in order. Who says practicality can’t also be sexy?

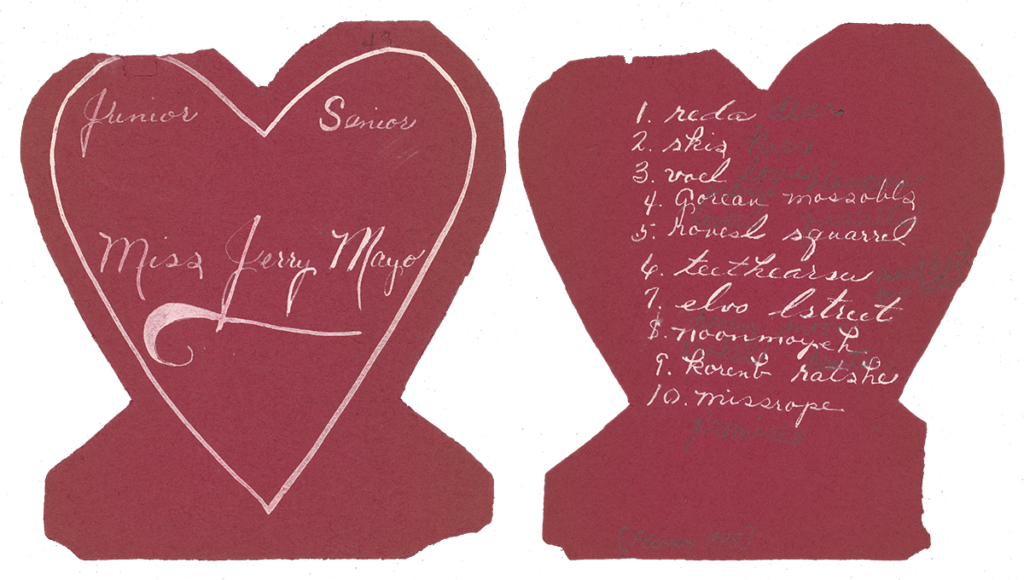

“Skis -> Kiss” (1945)

Dave Beveridge to Jerry Mayo

David “Dave” Beveridge of Beaufort was stationed along the North Carolina and Virginia coasts as a member of the Coast Guard Reserve during World War II. He met his girlfriend (and later, wife) Geraldine “Jerry” Mayo of Mesic, at a public dance for military personnel on the North Carolina coast. He wrote often to Jerry — some of the most playful, joyful love letters in the entire archive. This Valentine’s Day word scramble, with clues like “rovesl squarrel” (lovers quarrel) and “missrope” (promises) is typical of their correspondence: a little silly, a little suggestive and very clearly created with love.

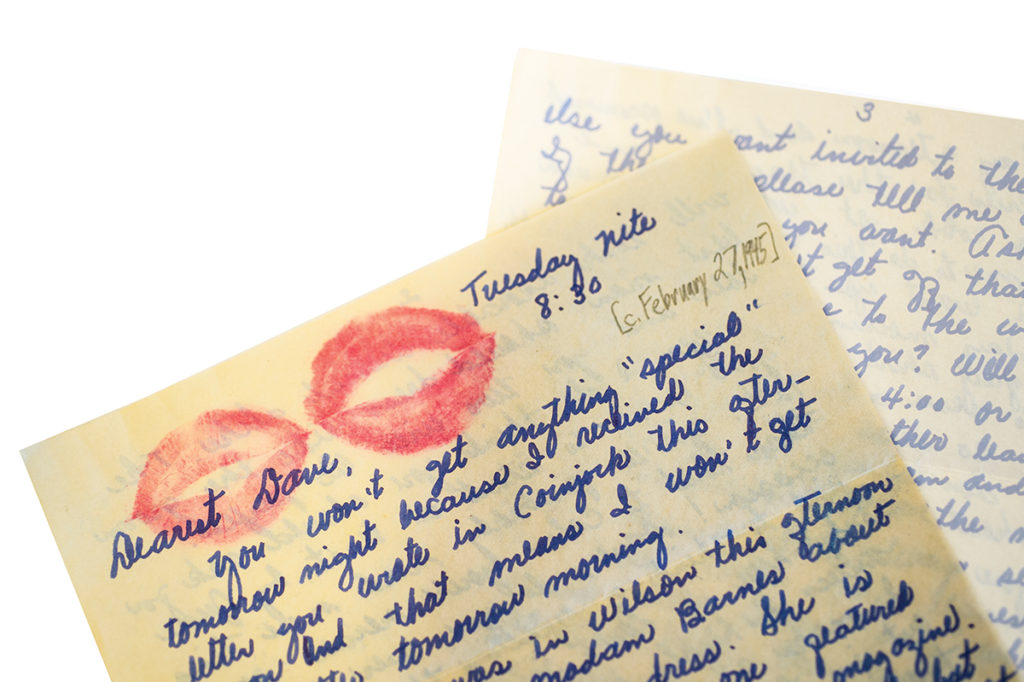

“Before The Wedding” (1945)

Jerry Mayo to Dave Beveridge

Most wartime correspondence from the homefront didn’t survive long enough to end up in the State Archives, so letters penned by women during this period are relatively rare. This one offers a snapshot of life in eastern North Carolina in 1945, as Jerry tells her fiancé about wedding preparations: talking with a seamstress in Wilson about her dress, recommending a pattern from Mademoiselle and thinking through the cake and the guest list.

“I asked at the bakery about the wedding cake and they’ve promised to ‘out-do’ themselves for me!” The lipstick kisses — so evocative of World Wars I and II — read like a thesis statement: These kisses are our past… let’s talk about how to make it our future, too. The two married in 1945.

“I Love Dave Dearly” (1945)

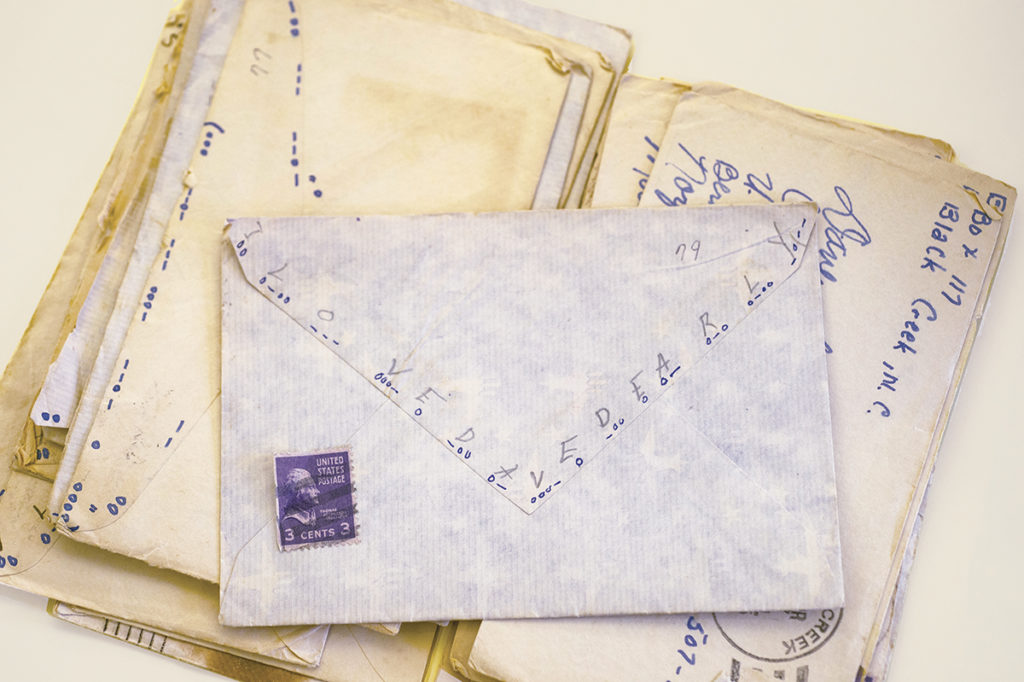

Jerry Mayo to Dave Beveridge

As Jerry and Dave’s relationship deepened, their correspondence became more prolific and creative — they knew how to keep things fresh! These envelopes with Morse Code messages must have made Dave smile when they arrived at his Coast Guard station. Jerry took a wartime necessity, coded letters, and flipped it into something sweet.

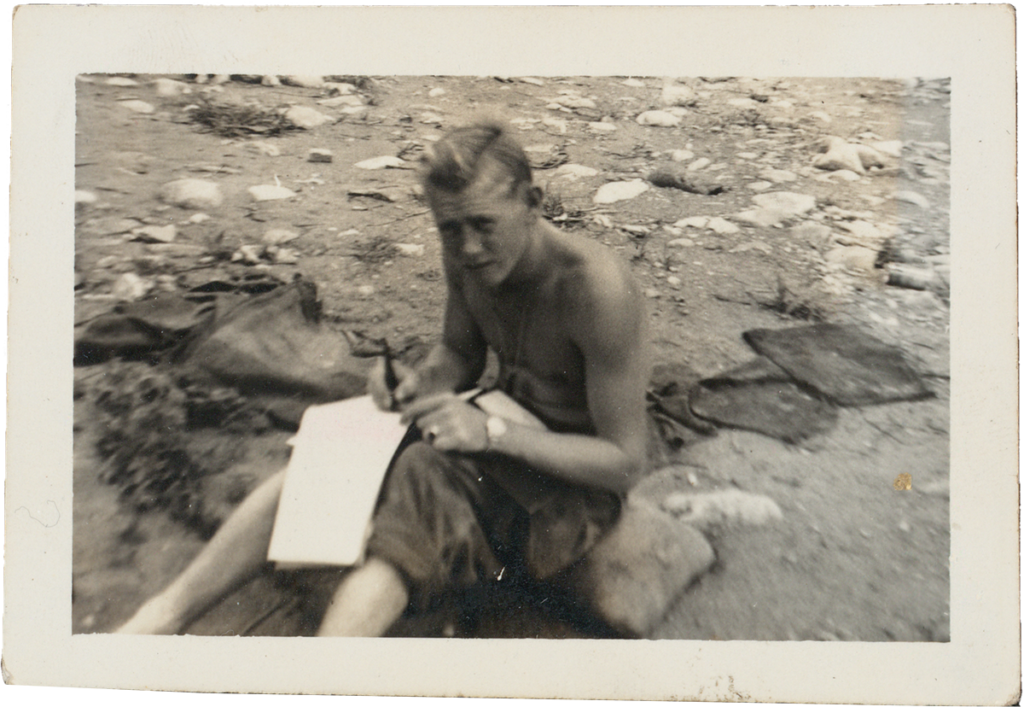

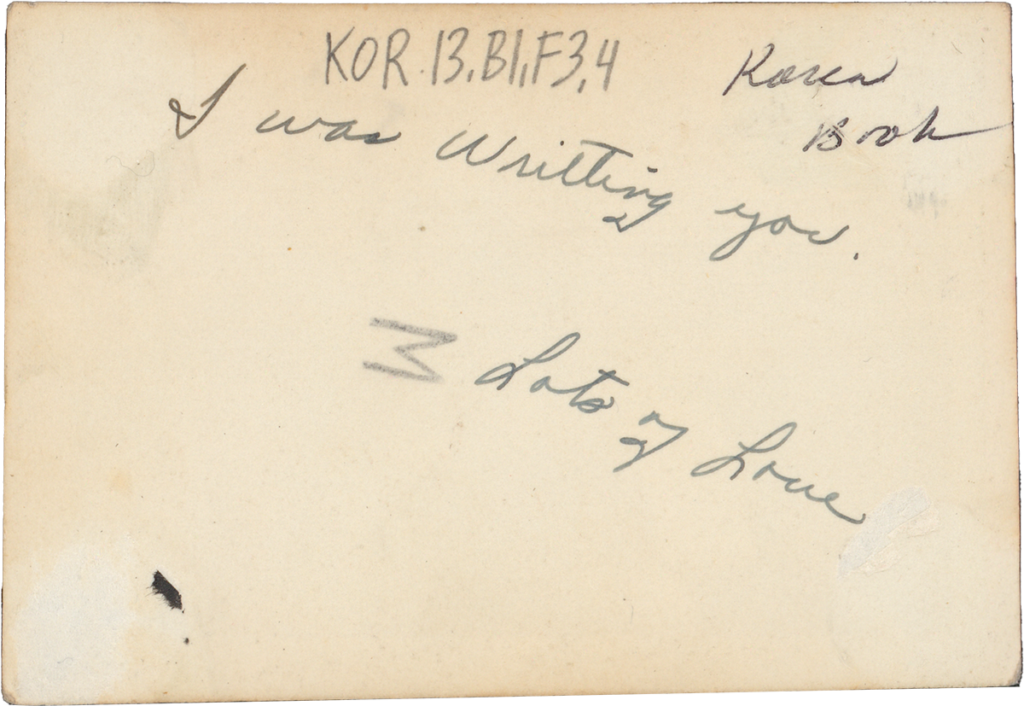

“I Was Writing You” (1951)

Lee A. Patterson to Mary Sue O’Quinn

Lee Patterson grew up in Harnett County and enlisted in the Army on Oct. 17, 1950, at Fort Bragg. He served during the Korean War as a Private, First Class. We don’t have the letters he wrote to his girlfriend (and later, wife) Mary Sue O’Quinn, but we can imagine this photograph was tucked into one of them. Is the emphasis on “was”? On “you”? Was it hot in Korea, or is the wardrobe choice for her benefit? In any case, it’s charming to think he wanted to record his devotion on camera — as though the words on the page just weren’t enough.

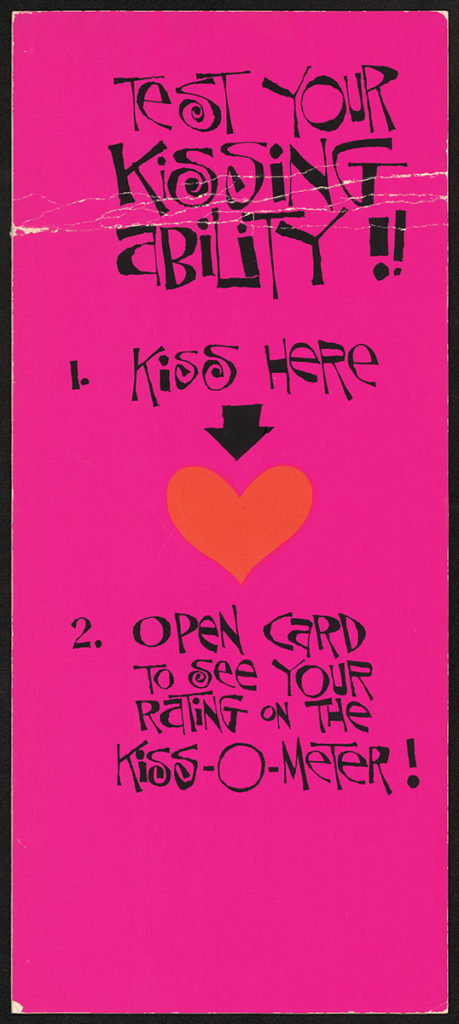

“All Right, Hot-Lips!” (1965)

Pete Maravich to Vada Palma

NBA Hall of Famer “Pistol Pete” Maravich spent a few high school years at Broughton, where he met his girlfriend, Vada Palma, who later donated her papers to the archive. Maravich’s Valentine to her is exuberant, sexy and creative — maybe his teachers should have offered some extra credit? He playfully challenges, “Kiss here… Open card to see your rating on the kiss-o-meter!” and inside, an illustrated Kiss-O-Meter smokes, admonishing, “All right, hot-lips… you don’t have to overdo it!” with a big “I love you.” It’s fun to imagine teenage Pete, such a showman on the court, chuckling at his own wit. Unfortunately, Vada didn’t think it was witty, and she let him know at the Valentine’s Day Queen of Hearts Ball…

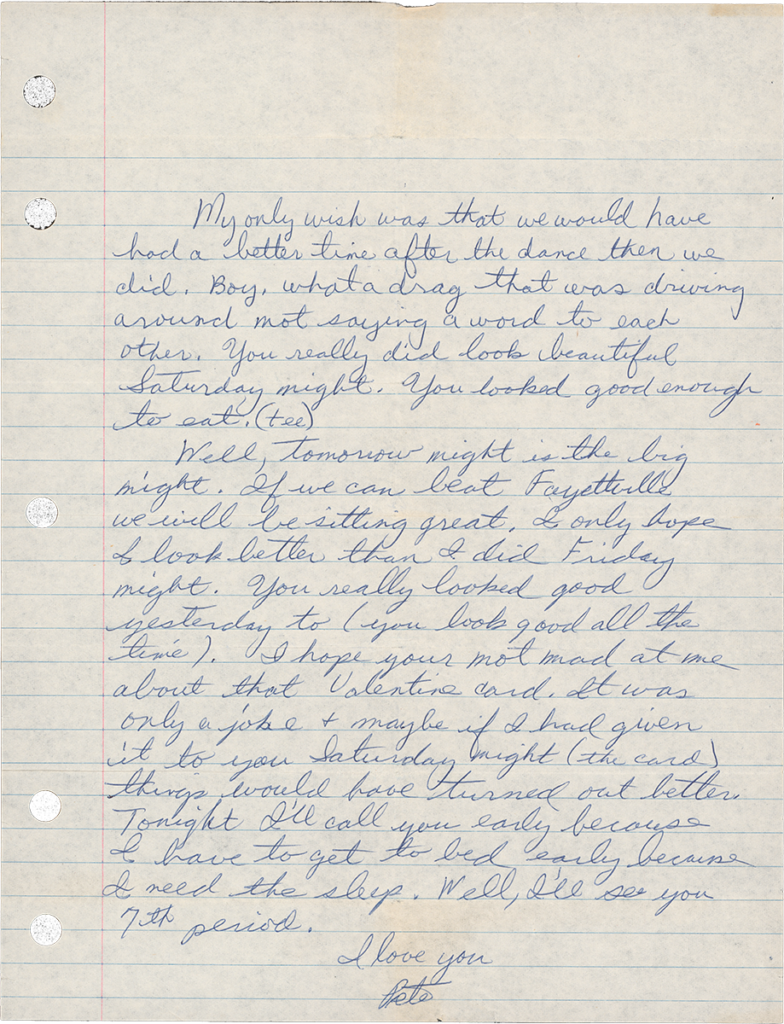

“Boy, What A Drag That Was” (1965)

Pete Maravich to Vada Palma

After Vada was miffed by Pete’s Kiss-o-Meter Valentine, the two attended Broughton’s Queen of Hearts Ball together. She might have looked “good enough to eat,” but their faces say it all: The dance — or at least, the after-dance — didn’t go as he’d anticipated. In this note, likely delivered between classes at school, Pete laments the night a little, flatters Vada more than a little, and of course, talks basketball. “I hope you’re not mad at me about that Valentine’s card. It was only a joke… Well tomorrow night is the big night.

If we can beat Fayetteville, we will be sitting great.” He signs off, “I’ll see you 7th period” — the same hint of longing we read in the World War II letters, though there are just hallways and hours between these two, not oceans and months. But the sentiment remains true: Isn’t time slippery in love? Especially when there’s making-up to do.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.