This Durham-based artist engages viewers with work that uses color and portraiture to express — and evoke — deep emotions.

by Wiley Cash | photography by Mallory Cash

I’ve met William Paul Thomas twice, both times inside an art gallery. He wasn’t present for our first meeting, but his work was. In October last year, I encountered his portrait of Alexander Manly, editor of The Daily Record, which was North Carolina’s only daily Black newspaper, as part of the Initiative 1897 exhibit at a gallery show in downtown Wilmington. The exhibit featured prominent Black civic leaders in the years preceding the 1898 race massacre, a violent coup d’état that saw Wilmington go from being one of America’s most successful Black cities to a place where racial terror and murder were used to take over Black-owned businesses and homes.

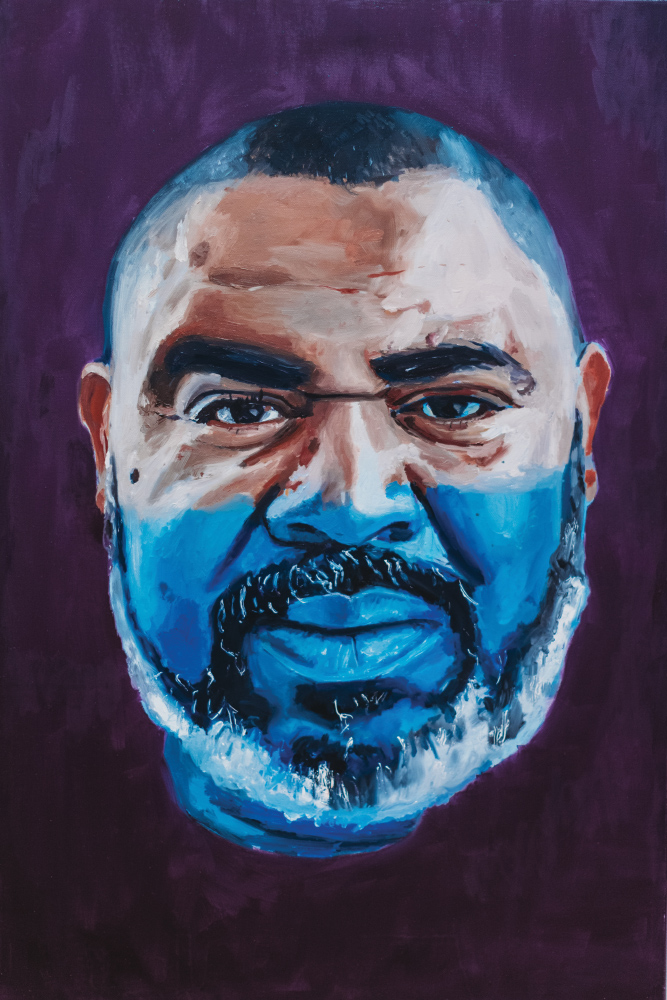

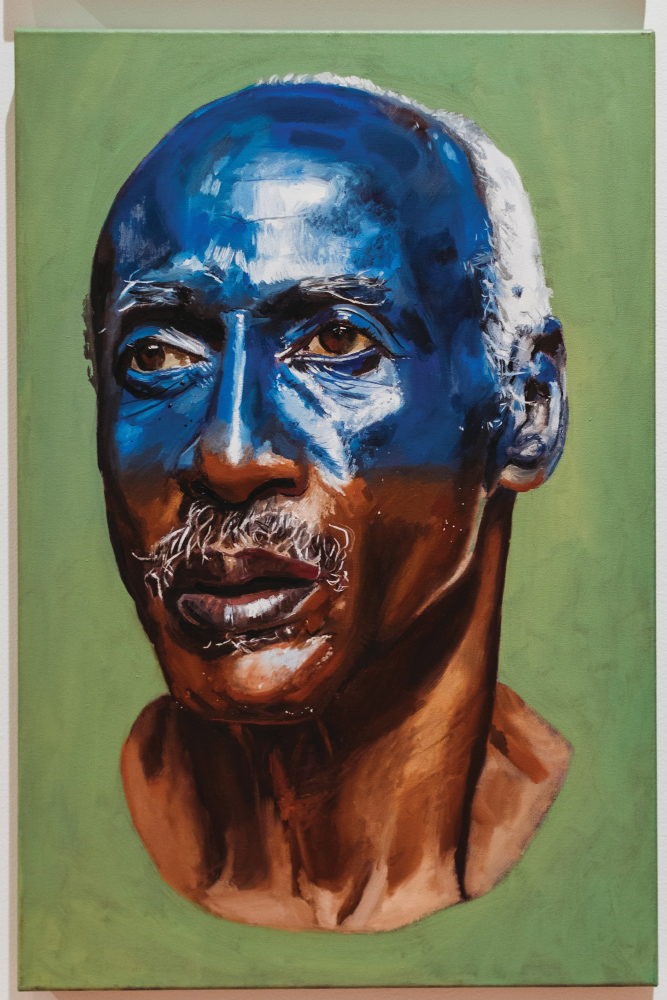

The second time I met William was in late February inside the Nasher Museum of Art on the campus of Duke University, where his portrait series Cyanosis was part of an exhibit titled “Reckoning and Resilience: North Carolina Art Now.” The subjects in the nine paintings are not as historically prominent as Alexander Manly, but they’re nonetheless important to William’s life. Each person is either someone he knows or someone he’s met during the course of a day, perhaps someone with whom he shared a passing conversation or a quiet moment that changed the trajectory of an afternoon.

The name of the series is taken from the medical term that refers to the blue pallor skin takes on when it is not sufficiently oxygenated. The idea first took root in a portrait William painted of his young nephew Michael. He painted half of Michael’s face blue to emphasize the color of his skin. Soon, the use of blue grew to represent the presence of deep emotions — perhaps trauma, fear, or uncertainty — that lie beneath the surface of people’s lives while they present a calm face to the world. In an online interview with Artsuite, William shared the unifying theme of the series: “My question through those paintings is: What would it look like if that trauma or adversity was shown on the skin? Would it invite people to be kinder to each other?”

On the day I finally met William in person inside the Nasher Museum, my wife Mallory, our daughters, and I arrived half an hour early. While Mallory unpacked her camera gear and set off to scout the museum for places to set up, our daughters and I wandered through the exhibits. When we found the exhibit featuring William’s paintings, we paused and stood in front of them. The nine paintings are all closely cropped portraits of Black men in rows of three, with a self-portrait of William sitting at the center. Each of the men is looking in a different direction, some of them seeming to stare right into the viewer’s eyes. Strips of blue color their faces in various places: across the eyes like a blindfold, over the nose like a mask, or covering the mouth like a gag.

William arrived, and we all introduced ourselves to one another. I’d been following his Instagram for several months and didn’t know what to expect from an artist who is wildly experimental and playful, while still earnest and sincere. The dichotomy a viewer might find in William’s work also seems present in his personality: he is formal but warm, thoughtful but quick to smile. He told us he’d just returned home on a flight from Chicago after spending the weekend at a wedding with his fiancée and their newborn daughter. We joked that he looked rested and photogenic for a man who’d spent the morning lugging bags, baby, and a car seat through airport terminals. His face softened for a moment at the mention of his being a new father, then he and Mallory got to work.

Meanwhile, our daughters were feeling inspired by the art in the museum. I tore pages loose from my notebook and fished pencils from my bag, and we found seats in the café and ordered snacks. I must have been feeling inspired myself because, like them, I began doodling on a blank page. But I couldn’t stop thinking about the faces of the men I’d just seen in William’s paintings, that strip of blue still hovering on the edges of my vision. I thought of deoxygenated skin and the videos I’d seen of Eric Garner and George Floyd, recalled their panicked voices saying, “I can’t breathe.” I looked down at my hands, one holding a pencil and the other resting on the table, the blue veins rolling atop the backs of my palms, not because my skin was deoxygenated or because I was experiencing latent trauma, but because my skin is pale and the blood inside them was moving freely.

After we left the museum, we followed William across the Duke campus to the studio where he teaches a painting class to undergraduates, which is just one of the courses he teaches at several nearby universities. Inside the classroom, one of his students was behind an easel, working on a project. He greeted her warmly, then I watched him return to his work on a portrait of a man named Larry Reni Thomas, a Wilmington native known as Dr. Jazz because of his extensive knowledge of the music’s history. The two men met when William was working on Initiative 1897. I asked William what interests him about painting people he meets. He lifted his brush from the canvas and considered my question, his eyes settling just above the top of his easel.

“For a long time, my art had been contained within an academic context,” he says, a reference to his Masters of Fine Arts degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and his teaching in the undergraduate classroom. “In portrait work, it’s important that the people that I invite [to be painted] don’t always belong to that same environment, so I’m having conversations with people who don’t necessarily have the same ties to UNC or Duke. I meet someone at the bus station and we strike up a conversation, and that’s a person I’m making a painting of. I start learning more about this area, or where I’m at, via those conversations. That’s how I’ve chosen to break away from a strictly academic environment.”

I ask him if he specifically looks for subjects outside of academic settings, and he admitted that he does, but that he’s also interested in introducing art to people who do not always think of themselves as being individuals who appreciate it.

“Sometimes I make visits to places with people because of the location. The Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill is right on Columbia and Franklin, and buses run all around that area. So if I was talking to somebody about art, there have been times — if they have the time — I’ll say, Let’s take this to the museum,” he says.

“Since I’ve identified museums and galleries as places I love to be as an artist and as a consumer of art, a lover of art, I don’t necessarily expect people to share that same interest. But if you tell me that you are not interested in art but you have not been inside a gallery, I challenge it and say, Then let’s go check it out,” he says. “I have relatives, friends, people I’ve met who feel like they don’t have a direct connection to art, and I disagree right away because I’m thinking, if you dress yourself in the morning or if you like a certain model of car or if you like a certain movie, you are making choices about the visual world that suggest that you have some interest in aesthetics, even if you don’t identify as an artist or a person who likes art. You can treat the museum that way, where you intuitively defer to your own tastes and go in there and judge whether or not you like whatever you see or feel moved by it based on your own experiences and not whatever education you have.”

When William considers how hesitant many people are to engage with art, he views his casual discussions with strangers as an opportunity that might lead them to a museum visit or to their portrait being painted: “It’s really of interest to me to engage in conversations where I try to demystify or deconstruct wherever that idea comes from.”

William is also interested in deconstructing the role art played in his own life, especially during his childhood. There could be no better representation of this than the bright pink concrete block that rested on the floor nearby. I’d already seen the block on his website, and I knew it had been painted to match a wall William’s mother had painted in the apartment where he’d grown up with his sisters in the Altgeld Garden housing project on Chicago’s South Side. He bent down and picked up the block at his feet.

“I extracted a single cinder block as a way to represent that memory,” he says. “It became a way to carry that experience forward as a part of my narrative. How much of her decision to paint that wall influenced my decision to become an artist? This domestic alteration, how did it impact on the way I see the world?”

I asked him about the differences between the burden of memory and the physical burden of lugging around a 40-pound block of cement.

“I did that unconsciously,” he says, referring to the burden of memory, “and now I’m doing it consciously. I’m choosing to carry this weight with me.” He smiles. “There’s never any good reason to carry a cinder block around with you, but there might also not be a very good reason to let any traumatic or negative moments that I experienced as a child have an effect me in the present. Nevertheless, for better or worse, the things we experience through our lives are carried with us. I’m definitely carrying home with me.”

I thought of his newborn daughter, a baby born in the Triangle, far from William’s Midwestern roots. What role would her father’s art play in her own conception of art’s role in her life? How would she carry her childhood with her?

He smiled, then he rested the block in his lap as if it were a newborn. “I hope she recognizes art as a normal, central fixture of her life, whether she is personally creating things or paying attention to the world around her. I hope she recognizes that it’s something valuable and precious.”

He continues: “I hope she has an interest in exploring and discovery. I hope she gets to know Durham and North Carolina in a way that’s really intimate. I want her to carry with her how rich the world can be wherever she is as long as she’s paying attention.”

If William’s daughter follows the example of her father — an artist who pays attention to his surroundings to capture the richness of a place and the people who inhabit it — I’ll bet she’ll learn to do just that.

______

This article originally appeared in our April, 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine