Author Daniel Wallace shares stories of holidays past, and the lessons they hold for us today.

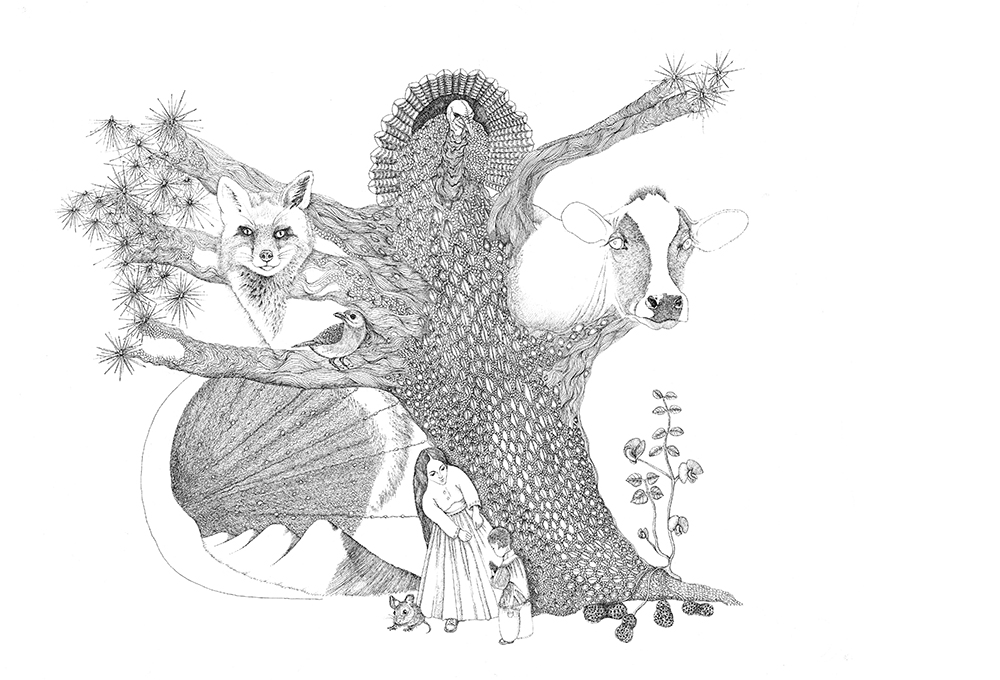

by Daniel Wallace | illustration by Ippy Patterson

The oldest family Christmas story I know is about my great grandmother, Nona. This is the century before last. Nona was a widow. As far as anyone could tell, Nona had always been a widow—some said she was born one. The truth is that her husband, my great grandfather, perished much too young in the salt mines of northern Alabama, leaving her alone with a brand-new baby, my grandfather, Ewing. As everyone who knows anything knows, Alabama was once home to the largest salt deposits in North America, something having to do with the shallow Cambrian seas that once covered the entirety of the state. But the mines were deep and dangerous and only the bravest of men ventured into them.

After the salt mine tragedy, Nona was penniless but proud, foraging for food in the forest to feed herself and her wee child. They moved into a straw hut abutting the tail end of the Appalachian mountain range. It was all they could afford.

All Nona had was an old milk-cow, named Deuce, and Deuce was about a day away from becoming their last supper when Nona had an idea. Ever resourceful and with a will of pig-iron, she became a milk lady. In the beginning she only had enough milk to service a few homes, delivering it in old tin cups. But after making her first few sales she upgraded, got a cart, some bottles, and before the sun was up she loaded the cart full of as many bottles as she could, pulled by the source of it all, Deuce. With her profits she purchased another cow, and another, and soon she became the most popular milk lady in town; but then again she was also the only one.

Even though she was making enough to feed herself and young Ewing, she was still too poor for a tree, and their hut— one tiny room, shoebox-small—was too teeny for even a shrub. But as she was reported to say right from the start, “We do what we can with what we might have.” She said it in the way that people who come from nothing say that sort of thing, all matter of fact, followed by a brief shrug of the shoulders.

So this is what happened on Christmas morning. Nona took Ewing off into the forest, pulled on a cart by the ever-loyal Deuce. And there they sat beneath the tallest, most majestic pine in the forest, an ancient giant of the Pinus clan, a tree so big it’s visible from space, they say. And there she would make a prayer, share some milk and give her son his present. As has been told to the subsequent generations of immeasurably spoiled and ungrateful children, Ewing was always thrilled with his interesting pinecone or a rock in the shape of a shoe.

But here is what was remarkable about that Christmas, and every Christmas they shared. They never spent it alone. One by one all the animals of the forest would creep up, join them there, slinking out of the forest-dark like shy friends. Deer, raccoons, wild hogs, bluebirds, hawks, turkeys, forest mice, coyotes, snakes, skunks, sometimes even a cougar or bobcat. Nona particularly loved a black bear she called Susie. They’d all keep their animal distance, but close enough for Ewing to see the warm steam of their collective breath. So the Christmas present really wasn’t a pine cone at all, nor a rock, it was the presentation and a celebration of the awesome myriad of life. She was actually giving Ewing the whole world.

I met Nona when I was three days old and she was 101. A week later she died in her sleep and Deuce followed soon thereafter. In honor of her passing no one in town drank milk for a month.

And now to her son, Ewing, my grandfather. Ewing was nick named “Dumbo” as a child, due to his larger-than-life ears. He was actually quite brilliant and used his ears to good affect: not only could he wear large hats; he could also hear everything. He could hear an owl sigh. He married my grandmother Lucille when he was but eighteen years old, after he fell in love listening to her hum.

Like his mother, Ewing was an inventive and resourceful entrepreneur. Would it surprise you to know that Ewing was the man who invented the boiled peanut stand? This is almost a true fact and let no one tell you different: the very first ever. He built it out of pallets and tree branches, using rusty nails pulled from old barns, and set it up on the side of the busiest road out of Cullman, a meager dirt road that disappeared after a hard rain and had to be repaved with more dirt next time the sun came out. His peanut stand was the most modern thing around at the time and people went no matter if they liked peanuts or not.

Peanuts grew wild in Cullman. An underground forest of them in Ewing’s backyard became an underground goldmine. The first stand was a great success—boiled peanuts from a roadside stand! What a concept!—and that success led to a second, a few miles down the road. He hired his cousins and cousins of cousins, friends of his cousins and their sons and daughters and soon the stands were everywhere, from Alabama down through Mississippi, sweeping into Louisiana and Florida, up through Georgia and finally into the Carolinas. Very few people know that most boiled peanut stands back then were franchises, but that’s what they were in the beginning.

A little part of every peanut sold found its way back to my grandfather’s pocket, and though he never became a rich man he was able to move his bride Lucille out of the thatched hut and into a proper house in town.

Christmas was a magical time in my grandparent’s home. My father got all kinds of presents: peanuts, tiny cars made of peanut shells, and best of all, peanuts painstakingly carved by Lucille, intricate portraits of Washington and Lincoln, or detailed landscapes of the French countryside, all from her imagining what it might be like. Find one today and it’s worth more than a Fabergé egg. Alas, most of them were eaten.

Lucille and Ewing saved and saved and eventually built an actual restaurant serving a great variety of foods. It was the only restaurant for fifty miles in any direction. Some people had never seen a restaurant before; many weren’t even familiar with the concept. Ewing and Lucille had to teach them to use a menu and then how to order their food from the lady in the pale blue frock. The good citizens of Cullman and beyond caught on quick.

People take restaurants for granted, but they shouldn’t. Restaurants are everywhere now, sure. But it wasn’t always like that. You may have my grandparents to thank for that. Maybe not.

With boiled-peanut money my grandparents bought a house big enough for a tree and had money at the end of the year to buy something for my dad, Eron, their only child. One Christmas morning my father got a pocket watch. On another he got a knife. The next, a bulky jacket, and then a pair of shoes—three sizes too big, for growing into. On his sixteenth Christmas they gave him a suitcase, on his seventeenth a compass. He saw where this was going. Year after year he had gotten one single thing until he got all the things he needed to make a life of his own and when he was 18 years old set off for the wider world.

On his first Christmas morning alone my father woke before the sun came up, fell into the Mississippi River and floated two hundred miles downstream to the Gulf of Mexico on a raft hastily assembled from twigs and mudgrass, and was finally rescued by one of the bravest and most intrepid sailors ever to roam the Gulf of Mexico in an old shrimp trawler: Joan Pedigo, the woman who would become my mother. They fell in love in about three-quarters of a second.

Family followed almost as quickly: me and three sisters, dogs and cats and a snake and a bird. Still: struggling. Lots of mouths to feed. It was my mother who had the idea for the salted peanut, which brought the two biggest industries in town—salt and peanuts—together for the first time. How no one had thought of it before her was a mystery. Thanks to the salted peanut for a period of years we were a family of not insignificant wealth. Later, a bigger company, the one that made complimentary peanuts—really nice people, for the most part—would put us out of his business. But until then every Christmas we traveled to a different country in the world. We’d plan our trips out beginning on January 1, studying the language, the mode of dress, learning their customs and histories: Mongolia, Argentina, Gabon—you name it. One cold Christmas we spent with Eskimos in Greenland. Atelihai means Hello, but that’s all the Inuit I remember. Because of my parents and Christmas our family has been almost everywhere there is to go. Name a place.

Yep. Been there.

Name another.

Been there too.

Christmas! Christmas seems made for tall tales: look at the big red one that persists to this day. These days our own Christmases aren’t quite as big as the ones that preceded it—no bears, I am sorry to say—but they are just as beautiful: North Carolina, where we have lived for the last forty years or so, makes sure of that. Until this year for decades running my family has produced postcard-worthy Christmases: the tree, the lights, the boxes wrapped in shiny paper, all of us gathered together next to the hearth beneath what felt like a dome of warmth and love.

But Christmas is not the same this time around. The pandemic has put a chink in our plans. Our clan is distant and scattered, and we do so many things in the world: we’re lawyers, doctors, construction workers, stage designers, Navy men and women, judges, paralegals, writers, scientists, artists, animal trainers. Every one of us knows a little bit about something, and together—could you bring us all together—we’d know practically everything. My second cousin is training snow-white pigeons to fly back and forth between our many homes, carrying Christmas greetings; another is perfecting the hologram, so even if we’re not together we will look like we are.

But then I think back to Nona, and those misty mornings she spent beneath that towering pine, with mountain lions and turtles, et al.; of my father, floating down the Mississippi clinging to a twig and a blade of grass. Which is just to say that yes, Christmas will be different this year, but it’s different almost every year, in one way or another. It’s what Nona said: We do what we can with what we might have: to hope and work for better times while making these times the best they can possibly be. That may be the story of our Christmas this year, but it may also be the story of all our lives.

Daniel Wallace has written six novels, including Big Fish: A Novel of Mythic Proportions. Wallace is the J. Ross MacDonald Distinguished Professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, his alma mater, where he directs the Creative Writing Program.