The prolific North Carolina author’s forthcoming book examines a topic close to home — the complicated life of his late brother-in-law.

by Wiley Cash | photography by Mallory Cash

It’s January, and I’m at the bar inside The Crunkleton on Franklin Street in Chapel Hill, where the winner of the 2023 Crook’s Corner Book Prize is about to be announced. I’m excited to be hanging out with my friend Daniel Wallace, who I met exactly 10 years before.

How do I know it’s been 10 years? Because this is the 10th year of the Crook’s Corner prize, and I was the inaugural winner, and I met Wallace for the first time at the awards ceremony back in 2013. He’s been one of my favorite writers and people ever since.

In 2013 my wife and I had just moved back to North Carolina after my debut novel was published, and to win this Southern book prize meant the world to me, as did the kindness of the writers I met the night of the award ceremony, including Wallace, Lee Smith, Allan Gurganus, Elizabeth Spencer and Jill McCorkle.

They made me feel like I belonged among them, and they set the tone for how I would treat and support the writers who came after me.

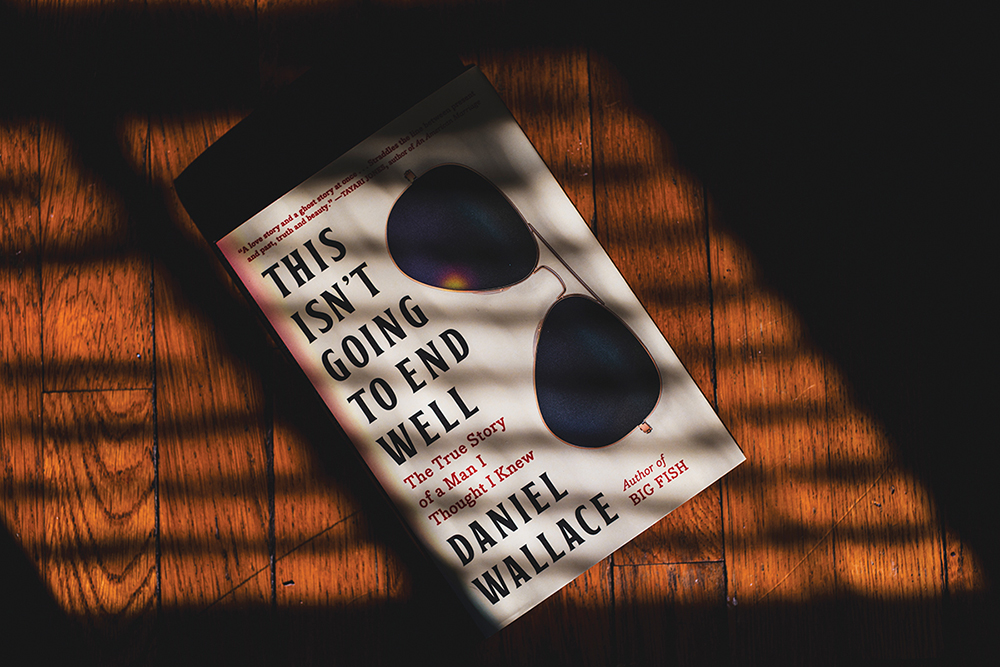

In the moments before this year’s prize winner is announced, Wallace and I stand around the bar and catch up. I ask him about the upcoming March release of the paperback of his latest book, This Isn’t Going to End Well: The True Story of a Man I Thought I Knew, a nonfiction portrait of his brother-in-law William Nealy, who was well known as an impossibly cool outdoorsman who made a name as a cartoonist who drew paddling guides to countless white water rivers throughout the South.

Wallace first met William when he was 12 and William was the cool, mysterious guy dating Wallace’s older sister Holly. To say that Wallace looked up to William is an understatement.

William died in 2001, and after Holly passed 10 years later Wallace discovered William’s journals while cleaning out their house. What he read inside changed his perception of William forever.

Wallace’s book is the result of his attempts to make sense of William’s life and the effect it had on so many people, including Wallace.

I ask him what it was like to write a book of nonfiction after forging a career as a novelist. The crowd is growing in the bar, and we are talking over the noise of other conversations.

“I never wanted to do nonfiction,” Wallace says. “The joy for me in writing fiction is putting the characters in motion and seeing what one of them does, and how it affects the rest of the characters in the story. There’s this joy that I get from making discoveries while following my characters.”

“In writing about William, were you also discovering something?” I ask.

Wallace sips his drink and thinks for a moment. “The process was similar to writing a novel, even though I had all this material. The character I was writing about — and I have to say that when I talk about William as a character I’m also talking about a person who was my brother-in-law and someone I grew up with — but when that person is part of your narrative, they do become a character.

And even I became a character in this book.” He smiles. “Although I like to think of myself as being real. I don’t know what your impression of me is.”

My impression of Wallace has always been that he is not only real, but that he is also very kind and funny. Every time he sees my two daughters he has some type of trinket to give each of them, and he’s always gone out of his way to offer opportunities to other writers, including in 2015 when he invited me to serve as the Kenan Visiting Writer at UNC-Chapel Hill.

As to his sense of humor, when I asked him for a sample syllabus, he sent me what he referred to as the “required syllabus for all creative writing students.” His novels were the only books on it.

My niece Laela, who’s a junior at the nearby North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, is interested in publishing, so I’ve brought her along for the evening.

When I introduce her to Wallace I tell her that I met him 10 years ago at the first Crook’s prize party and how that evening felt like the beginning of my career.

“It was a special night,” Wallace says wistfully. “Of course Wiley’s novel was the only submission that year, but we were all still really happy for him.”

We all laugh, but the conversation takes a serious turn when we reflect on what seems like the constant changes in Chapel Hill’s cultural landscape. Crook’s Corner is a great example.

The restaurant opened just down Franklin Street in Carrboro in 1982 and quickly became a staple of the Southern food movement, garnering praise and culinary awards. But, like many restaurants, Crook’s closed its doors during the pandemic, and for now they’re still closed, although there are rumors that it might reopen.

Wallace followed William and Holly to Chapel Hill and moved there permanent- ly around the time Crook’s opened. He’s seen so many changes over the decades in a place that he chose because of its creative vibes and how welcoming it was to writers and artists.

“There was a simplicity to it then,” Wallace says. “Part of it I’m sure has to do with youth, but when you live in a place that doesn’t have a building over one-and-a-half stories tall, you feel bigger in that town, and you feel more real in a way that you might not feel now.”

Wallace had begun his undergraduate studies at Emory University, and when he transferred to Chapel Hill to be closer to William and Holly he found himself in a creative writing class led by Lee Smith.

“It was at 8 o’clock in the morning,” he says, “and of course Lee brought her trademark power, personality and joie de vivre to it, which made writing fun. And she was fun. I loved how she taught. It was an adventure with language and story and character.”

Wallace left UNC before receiving his degree and went to work for his father for two years in the import industry. But he couldn’t shake his desire to write — or his love for Chapel Hill.

“I moved back here because of the community,” Wallace says, “and because, of course, Holly and William were here. But a major part of that decision was that it’s hard to exaggerate the importance

of going to Harris Teeter and seeing Lee Smith shopping.

The life of a young writer looking out from this hole that they’re in is made so much brighter when you can see that real people have this real job, just like you want to do.

You’re not intimidated as much by the possibility of entering that world when you have these roving mentors, these mentors that you haven’t even necessarily met yet, but you see them walking around. You see Doris Betts on the street corner, waiting for the light to change. It’s human, it makes writing a human act.”

The evening is almost over. The announcement has been made, and winner Bobby Finger has said a few words to the audience. I speak about the power of recognizing debut writers and how important it is to be a member of a community like the one Crook’s Corner and Chapel Hill’s writers have built over the years.

Wallace is gone by the time I step back into the audience. My niece and I find our coats and walk out onto Franklin Street, the cold winter air hitting our cheeks.

I can see wonder in her face as we walk back to the car, something I’ve heard people refer to as the “Chapel Hill Magic,” the same thing Wallace felt in the early ’80s after riding his bike to The Cave to play pool with William.

The buildings are taller now, some of the old places have closed, and some of those old people are gone. But this little town, and people like Wallace, can still make you feel big.

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.