Two 18th-century porcelain tea caddies at the North Carolina Museum of History reveal the significance of the women of the Edenton Tea Party.

by Hampton Williams Hofer | photography by S.P. Murray

These days, we’re all about coffee. But three centuries ago, it was tea.

A staple of the colonists’ trade with England, tea anchored social gatherings and served as a sign of refinement, particularly among those who delighted in its lavish accessories, from hand-decorated teapots to Chinese-export cups and saucers. But two porcelain caddies — embellished vessels used to store leaves — on display at the North Carolina Museum of History represent a lot more than just the tea culture of their time.

It all started with a wealthy Edentonian named Penelope Barker. Her third husband had sailed to England in 1761 and was unable to return for 17 years due to the British blockade of American ships. While she was in charge of their estate, the drive toward independence was growing in the colonies. Patriot leaders encouraged women — the main consumers of retail goods — to boycott British imports. Barker took it to heart, making the rounds of Edenton, garnering support from local women for a boycott of British teas and textiles.

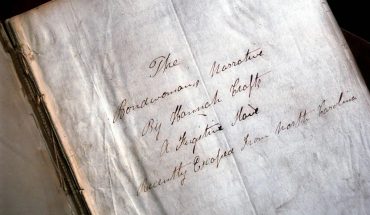

On the afternoon of October 25, 1774, 51 women in Edenton gathered to sign a resolution: they were fed up with foreign rule. Their document, printed in the colonies and sent to England, stated that they would “not promote ye wear of any manufacturer from England, until such time that all Acts which tend to enslave our Native Country shall be repealed.” They even signed their real names in this bold protest, which later became known as the Edenton Tea Party.

It was the first significant political movement in this country staged by women. And whether or not tea was actually present at the signing of the resolution, Penelope Barker likely had one of her last sips of pre-Revolution tea brewed from leaves stored in one of the caddies now on display at the museum.

The history museum’s largest exhibit, The Story of North Carolina, traces 14,000 years of our state’s history through all sorts of media, dioramas, interactive features, and artifacts. Beginning with American Indian life and moving through European settlement, museum visitors reach the story of the American Revolution. There, behind the glass, sit three relics from the Edenton Tea Party. The first is a large punch bowl, dating back to the 1760s, that was owned by Winifred Hoskins, secretary of the Edenton Tea Party. The second two are tea caddies, one of which may have been owned by Penelope Barker, and another that belonged to Lydia Bonner and Mary Bonner Blount, mother-daughter signers of the resolution.

Well-preserved pieces from the 18th century do not pop up every day, so artifacts like these, donated by descendants of original owners, are exceptional finds. The caddies were used to store tea leaves — an exceedingly expensive indulgence, and they look the part. Decorated in underglaze blue, with overglaze enamels, the Bonner caddy was likely made in China, with a hand-painted blue design in the vein of a ginger jar. Hot water would have been brought up from the kitchen to make the tea, and caddies like these would have resided in living rooms, witnesses to the important business of patriot women. When British tea was off the table, colonists made their own, using mulberry leaves, lavender, and other local herbs.

The petition of the Edenton Tea Party, while applauded in the colonial press, was the object of mockery across the pond. In the NCMH hangs a rendering of a cartoon published in the London press, depicting the women of the Edenton Tea Party with masculine faces and loose morals. “It’s a great piece of political satire,” says chief curator RaeLana Poteat. “It really lets you know what men of that time thought about women taking this sort of action.”

Barker was progressive, outspoken, and brave. She famously earned the respect of British soldiers in later years when she used her husband’s sword to slash the reins out of the hands of a soldier attempting to steal her horses. It’s no wonder that she’s the same woman who assembled fifty others to her cause; as she wrote, “We cannot be indifferent on any occasion that appears nearly to affect the peace and happiness of our country…”

While Barker is the most talked-about member of the group, all 50 women who signed the petition were equally important, and had as much to lose, says Annette Wright, a volunteer at the Penelope Barker House Welcome Center in Edenton. “There were wives of merchants and tavern owners, the daughter of a governor, the mother of an English Baronet,” says Wright. “The youngest woman to sign was 16 and the oldest was a grandmother.”

As NCMH visitors continue through The Story of North Carolina, the legacy of the women of the Edenton Tea Party paves the way for other firsts for women in our state: one hundred years later comes Mary Jane Patterson, a free Black woman from Raleigh who became the first African American woman in the United States to receive a Bachelor of Arts degree. Another hundred years after that comes Susie Sharp, North Carolina’s first female Superior Court Judge. The timeline of intrepid women in our state’s history marches on.

Barker and her comrades won’t soon be forgotten, thanks to the meticulous preservation of relics that help us understand and relate to the past. Edentonians, with proud teacups on their town license plates, certainly aren’t forgetting. “The legacy of the Tea Party is alive and well in Edenton,” says Chris Bean, who has held supervisory responsibility over the Penelope Barker House. “But the real legacy is the pride that everyone feels in the bold political action of these women, so far beyond imagination in their time.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2021 issue of WALTER.