The acclaimed artist has painted landscapes from Tuscany to Normandy, but these days he’s focusing on North Carolina.

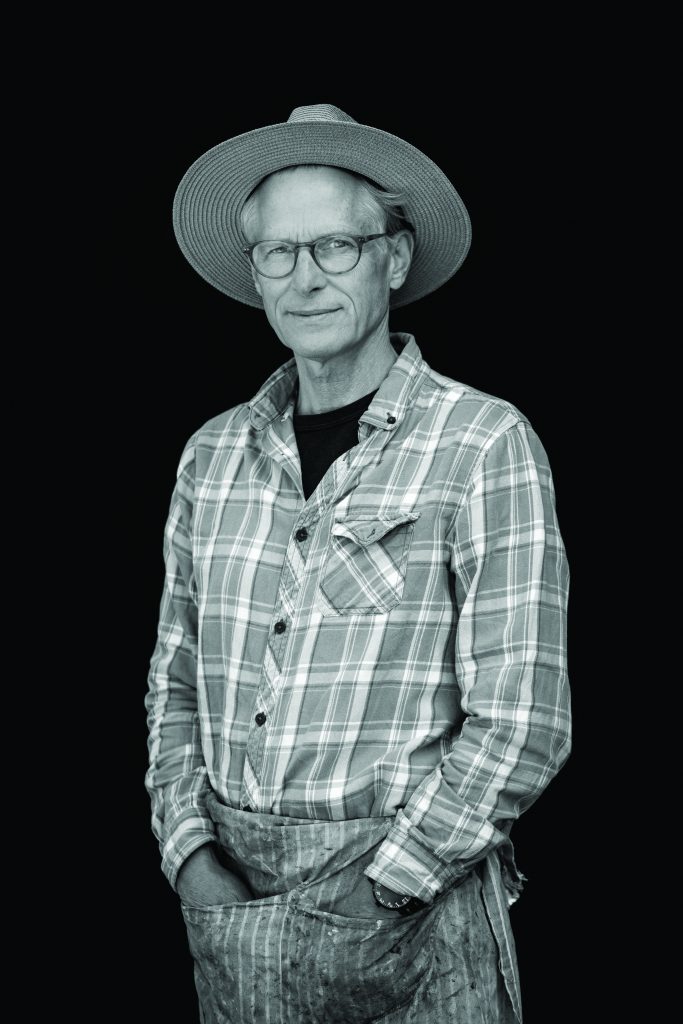

by Liza Roberts | portrait by Lissa Gotwals

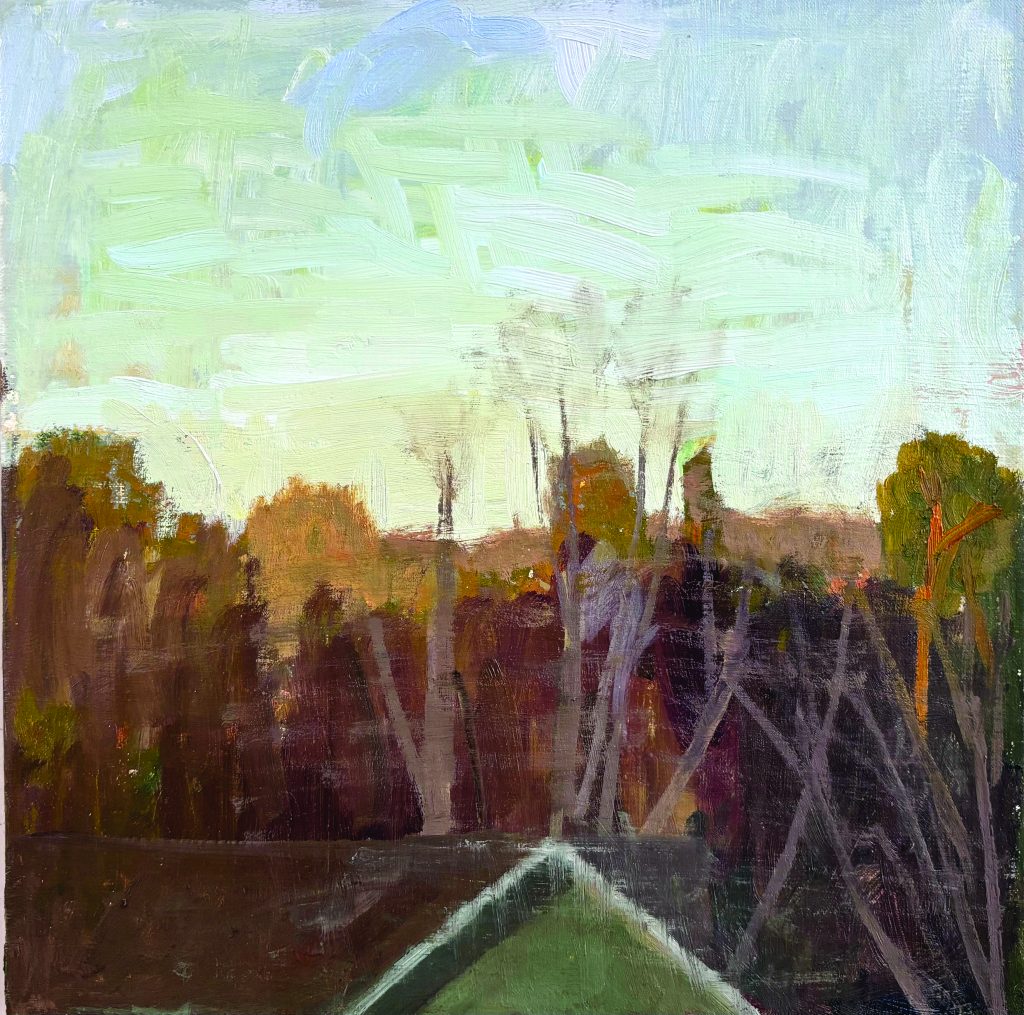

Before John Beerman paints a landscape, he studies the place that’s caught his eye and picks a particular day and time. Maybe it’s a low-lit evening in fall, or maybe it’s a morning hour that only exists over a span of days in spring, when the angle and energy of the sun provides a certain glow. And then he goes there, day after day, at that appointed hour, building his painting bit by bit until the moment is over — the hour has passed, the shape of light has changed, that bit of season is gone.

One spring morning not long ago, he arrived at a field at Chatwood, the Hillsborough estate owned at the time by his close friend, the author Frances Mayes. Beerman arrived well in advance of his chosen hour, because it takes some time to set up his easel. He has an intricate system of clamps and slats to hold boards in place that will serve as a perch for both his canvas and his paint. His paint is of his own making, too: it’s a homemade egg tempera, created with pigment and egg yolk that he keeps in an airtight jar.

To accompany him on one of these plein air excursions is to realize that Beerman doesn’t just look like Monet at Giverny, with his straw hat, wooden easel, linen shirt and leather shoes, but that he sees like Monet: he views the natural world with the same kind of reverence. Beerman studies the landscape as if it has a soul, character and moods. He learns its nuanced beauty out of a deep respect — and only then does he paint what only he can see.

“I have always found the natural world a gateway to the greater mysteries and meanings of life,” Beerman says. At a time when the world faces so many problems, he says, “it’s important to see the beauty in this world. It is a healing source.”

Beerman has often ventured to notably beautiful places around the world to find this gateway. To Tuscany in springtime, coastal Maine in summer, the glowing shores of Normandy or the estuaries of South Carolina. Recently, he is choosing to stay closer to his Hillsborough home. “Sometimes I feel rebellious against going to those beautiful places and painting those beautiful sights,” he says. “My appreciation and love of the North Carolina landscape continues to grow. I feel we are so fortunate to be here.”

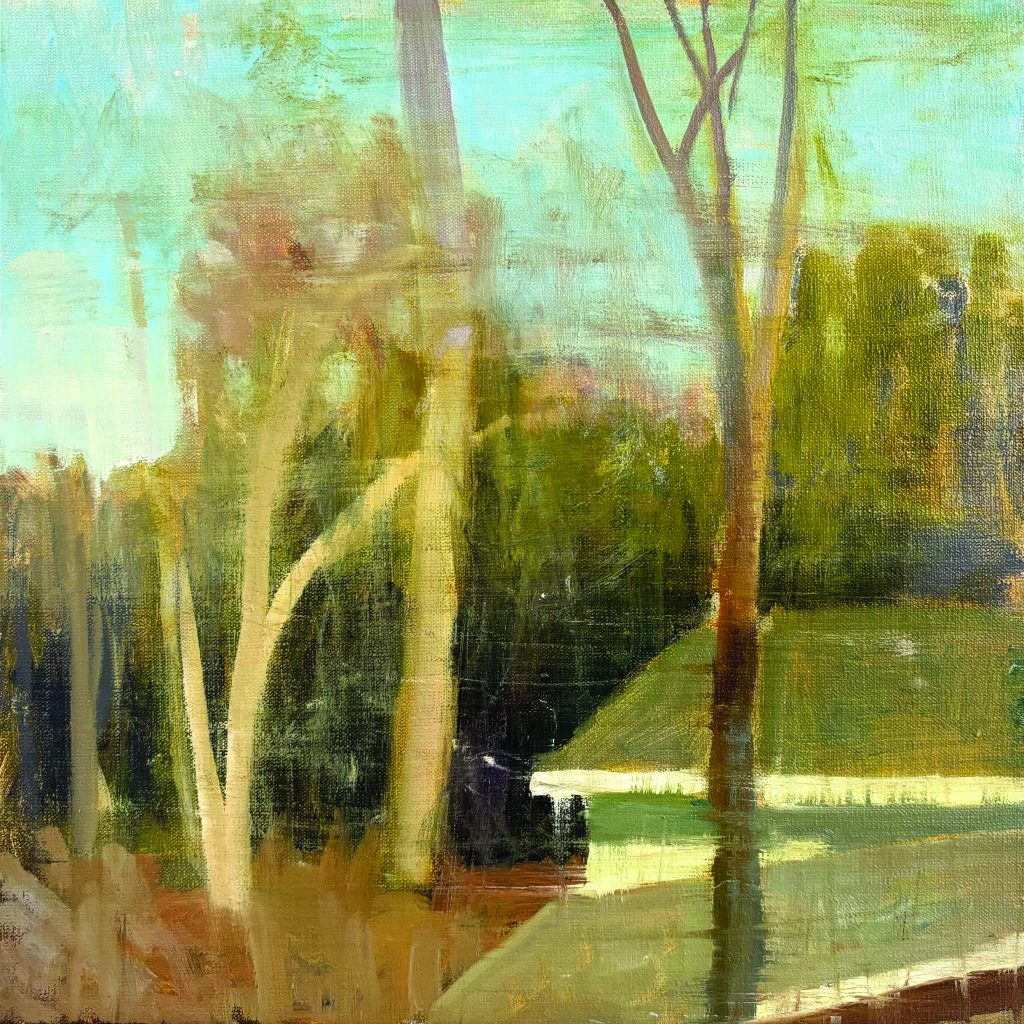

This year, so far, he has been painting the views from his studio windows. “I am struck by the idea that every day the sun moves across the sky, the seasons change,” says Beerman. “I’m looking at one house in five different versions throughout the day.”

The particular house on his easel now is a millhouse currently under renovation. He has a bird’s-eye view of the millhouse from his second-story studio, but it constantly evolves with the men working on it and the light that suffuses it.

What Beerman is painting, though, isn’t “a house portrait,” but an attempt to capture “the luminosity of that particular light.” Also compelling him is the energy of the project at hand: “The guys working on the house are just as interesting to me,” he says, so he has begun to paint them into the scene, even though figures have rarely appeared in his landscapes.

The ability to revisit the subject of his fascination day after day as he completes a painting is a refreshing change, he says. Typically, he’d paint small oil sketches in the field, then bring them back to the studio to inspire and inform his large oil paintings. Here, he can continue to study parts of the house, the men and the project that elude him; he can “get more information” as he goes.

But if his proximity to his subject has changed, Beerman’s essential practice has not.

“I’ve always felt a little bit apart from the trend,” he says. “I love history. And one also needs to be in the world of this moment, I understand that. I’m inspired by other artists all the time, old ones, and contemporary ones… Piero Della Francesca, he’s part of my community. Beverly McIver, she’s part of my community. One of the things I love about my job is that I get to have that conversation with these folks in my studio, and that feeds me.”

Beerman’s work keeps company with some of “these folks” and other greats in the permanent collections of some of the nation’s most prestigious museums as well, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the North Carolina Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art and governor’s mansions in New York and North Carolina.

The paintings that have made his name include celebrated landscapes of New York’s Hudson River early in his career (he is a direct descendent of Henry Hudson, something he learned only after 25 years painting the river), of North Carolina in later years and of Tuscany, where he has spent stretches of time. They all share a sense of the sublime, a hyperreal unreality, a fascination with shape and volume, space and light, a restrained emphasis on color and an abiding spirituality.

“Edward Hopper said all he ever wanted to do was paint the sunlight on the side of a house,” Beerman says. “And I so concur with that. It’s as much about the light as it is about the subject.” A painting of the lighthouse at Nag’s Head includes only a looming fragment of that famous black-and-white tower, but it’s the glow of coastal sun Beerman has depicted on its surface that make it unmistakably what and where it is.

“With some paintings, I know what I want, and I try to achieve that. And other paintings start speaking back to me,” he says. Beerman’s talking about another painting, of a wide rolling ocean and a fisherman on a pier. As he painted it, childhood memories of Pawleys Island, South Carolina, came into play: “In this old rowboat, we’d go over the waves. And in doing this painting, that came in… ahh, maybe that’s where I am. Sometimes it bubbles up from memories that are right below the conscious.”

The rhythm of the work he has underway now suits him well, he says: “I’ve traveled a good bit, but I’m a homebody. I like cooking on the weekends, and making big pots of this or that. I love being able to walk to town, or ride my bike to town.”

And he’s eager to stick close to his chosen subject. “I love the long shadows of the winter light,” he says. “I want to capture it before the leaves come back on the trees. I have that incentive: to get in what I can before the leaves come back.”

Whatever he’s painting, Beerman says he’s always trying to evolve: “One hopes you’re getting closer to what is your core thing, right? And I don’t want to get too abstract about it, but to me, that’s an artist’s job, to find their voice. I’m still in search of that. And at this time in my life, I feel more free to express what I want to express, and how I want to express it. I don’t feel too constrained.”

This article originally appeared in the April 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.