This longtime Penland-based artist with Puerto Rican roots sculpts soulful, fantastical people from clay and other media.

by Liza Roberts

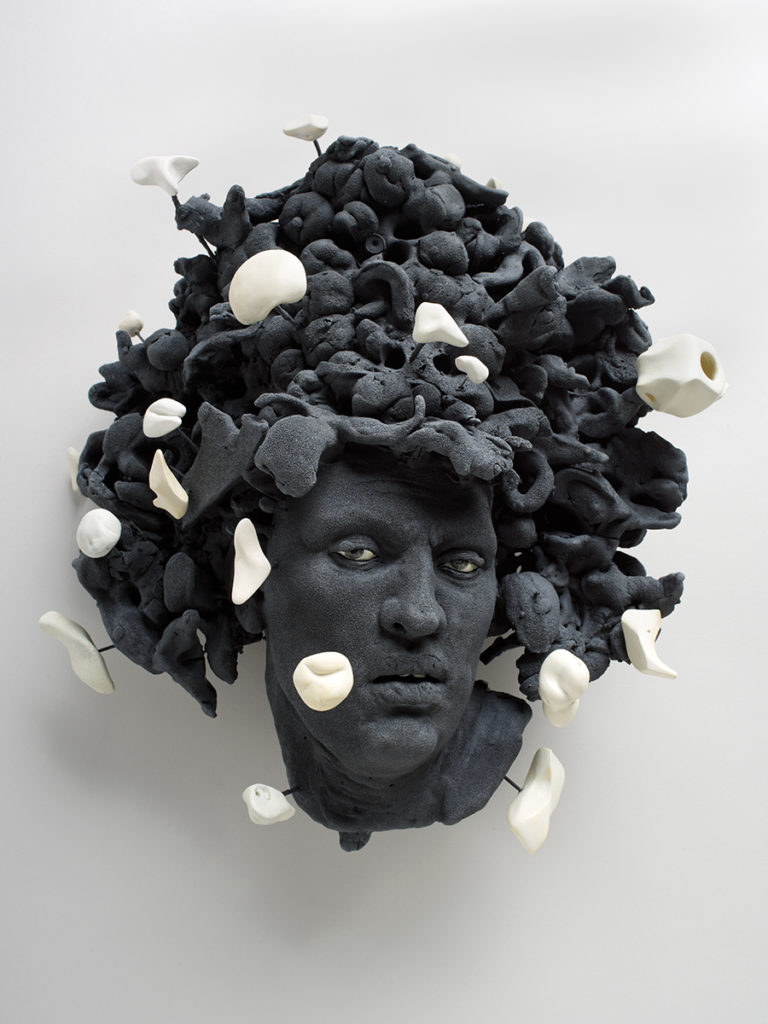

“I was always very creatively inclined, and very restless,” says sculptor Cristina Córdova, as she moves — glides, really, with ease and focus — around a massive head she’s shaping out of clay in her Penland studio. She molds it with elegant hands, quickly, decisively, certain about what she wants this clay to be. Like the work that has made her name, it will become real, it will be soulful, thoughtful, disarming, alive. Its eyes will be hollow, but they will express sadness; its face will be impassive, but it will express stoicism.

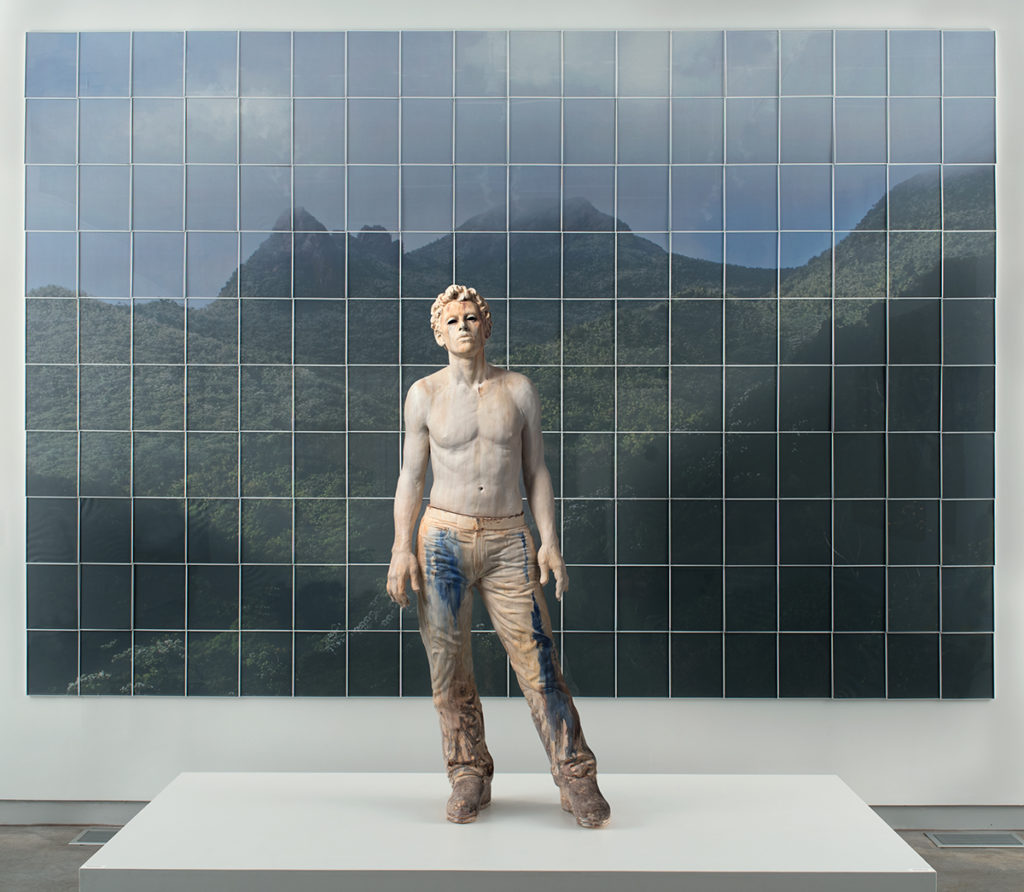

Córdova is known for her remarkably lifelike figurative sculptures in clay, which typically range from diminutive to lifesize. They’re often accompanied by fantastical environments — sometimes two-dimensional scenery like a postcard view of a place, sometimes shapes or foliage. Often, her hyper-realistic, exacting bodies or faces are arranged in contrast with elements that defy explanation.

Córdova grew up in Puerto Rico and earned her undergraduate degree from the University of Puerto Rico and an MFA in Ceramics from the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University before moving to Penland in 2002 for a residency at the renowned Penland School of Craft, subsequently making the campus her home.

Currently, her award-winning work is in the permanent collections of the Mint Museum in Charlotte, the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Puerto Rico and many others. Córdova credits her mother with nurturing her creativity from an early age, steering her toward the career that has made her one of the most respected sculptors in North Carolina and a pillar of the Penland community. She credits a ceramics teacher with first showing her the potential of clay, the possibility that it could go beyond representation to “embody any idea.”

At that point, she says, “the material revealed itself to me in this really exciting way. And I never looked back.” Still, she took some time to settle on her subject. Gradually, she says, “I started to become a little bit more excited, more empowered to start specifically to focus on the figure.” It was a focus borne in part by her heritage.

Growing up Catholic in a house with, she says, literally hundreds of depictions of saints all around her, she internalized the idea of using a figurative work of art “as a way of harnessing your emotional energy and pulling it into something sacred.”

Though her current work is not religious, Córdova finds that it’s understood “at a different level” in Puerto Rico, where “Catholicism is not a choice, it’s woven into the culture, so people come to the work with a shared insight.” Her subject may come naturally, but that doesn’t make it easy. Depicting the figure in clay is a challenge.

Early in her career, Córdova found herself stuck in between two worlds, the sculptural tradition of working in the round with a live model and the more organic ceramic tradition. Eventually, she settled on a hybrid approach, one that includes not a live model but a series of blueprints that provide her with the measurements and dimensions she needs to create a sculpted three-dimensional figure.

The head before her on this particular day — not necessarily a man nor a woman, as is sometimes the case with her figures — is imagined instead of representational, and so its blueprints are designed merely to keep her to scale, leaving room for improvisation. In other instances, she uses a series of photographs to help her create more precise blueprints.

Córdova gestures to the head before her, saying “I’m called right now to do things that are big, almost monolithic. I think it has something to do with what we are experiencing [with the pandemic]. I’m not interested in intimate or narrative-oriented work. I’m interested in big statements.”

Big statements seem called for by the importance and enormity of our internal worlds in a situation like the pandemic, she says. “The isolation, the uncertainty, the newness — to have to take all this in without being able to respond in our normal ways… recourse is very limited. So you’re holding this inside of you, and that’s all you can do, is hold it, and witness it, and be with it. We need a big container for that right now. So I’m making big containers.”

It’s not a simple process. Beginning with a large, donut-shaped piece of clay that’s laced with sand and paper pulp for stability and structure, Córdova then patches in a perpendicular slab, then another, and then adds rings of clay, providing “the basic topography.” From there, she more fully fleshes out and articulates the shape of the head and face.

Having worked “all over the place in terms of scale” over the course of her career, the process of working in such large dimensions now excites her: “This to me is a starting point. I really want to get bigger. I have no idea how I’m going to do that.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of WALTER magazine.