Originally from Vietnam, the artist pivoted from a career in fashion to one in art, using material with ties to his own cultural history.

by Liza Roberts | images courtesy Kenny Nguyen

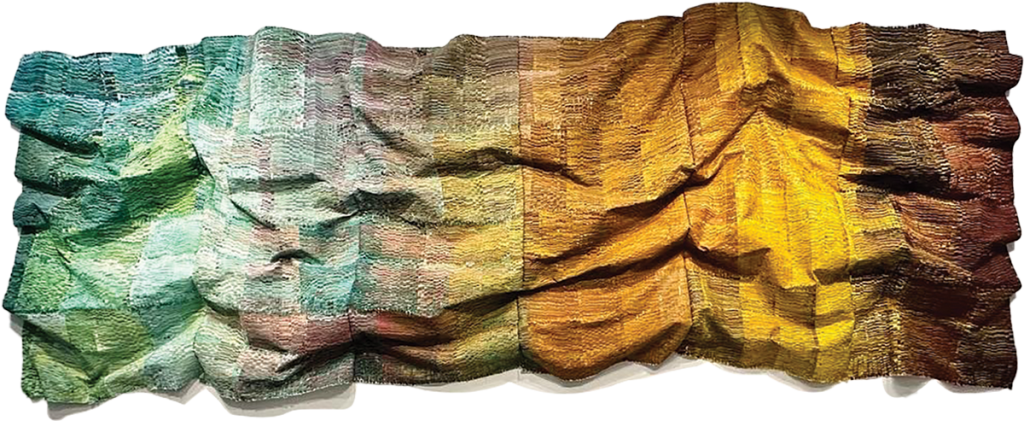

“Every time I start a piece, I imagine there’s a body underneath it,” says Quoctrung Kenny Nguyen, a former fashion designer who makes rippling, three-dimensional sculptures out of paint-soaked silk. “Instead, there’s this absence of a body, in sculptural form. It’s beautiful like that.”

Torn into strips, dredged in paint and affixed to unstretched canvas, Nguyen’s silk segments fuse to become a malleable but sturdy material that he molds with his hands and pins in place. Every time he hangs a piece, he changes the pin placement — and with it, its shape, shadow and energy. Some have a “more architectural feel,” others are more organic.

These works explore and illustrate Nguyen’s experience with reinvention, cultural displacement, isolation and identity.

His chosen material — with its direct ties to the cultural history of his native Vietnam, where the fabric is revered and traditional “silk villages” keep ancient techniques alive — is a key component. “Identity is changing all the time,” he says, “and the work keeps evolving, in a continuous transformation.” It all begins with the fabric in his hands.

“Silk is already a transformation: from the silkworm, to the silk thread, to a piece of silk. So it’s holding a metaphor.” More than one: “People see silk as a very delicate thing,” he says, “but actually it’s one of the strongest fibers on earth.”

Nguyen’s work has earned him solo exhibitions and dozens of awards, residencies, grants and fellowships all over the world. It began to take off commercially in a big way during the pandemic, when he started using Instagram to share images of his pieces, and after Los Angeles based Saatchi Art named him one of the “best young artists to collect” under the age of 35 from around the world.

He now has art consultants and galleries representing his work all over the country and in Europe, and has had to move his studio out of the garage of his family home and into a former textile mill to keep up with demand.

He no longer works alone, with three assistants (all art students from UNC Charlotte) helping him with prep work, photography and studio management. His biggest challenge is no longer finding an audience; it’s managing the business.

Nguyen couldn’t have imagined this kind of success when he immigrated here in 2010 from Ho Chi Minh City with his family. He was 19 and had a BFA in fashion design from the University of Architecture Ho Chi Minh City. But he couldn’t find a job and spoke no English. “It was just a culture shock. You can’t communicate with anybody. You feel so isolated. I was struggling,” he says.

Art called him. Nguyen enrolled at UNC Charlotte to study painting — Davidson artist Elizabeth Bradford was one of his teachers — and found himself yearning for a way to incorporate his own culture and passions into the work. In the end, they came together was a happy accident.

During the summer of 2018, three years out of UNCC, Nguyen had just arrived at an artist’s residency in rural Vermont, where he planned to continue painting the “very flat, very traditional” types of canvases he’d been creating until that point.

But in his rush to get out the door, he left a container with most of his colorful paints and brushes behind. In fact, he realized that he’d managed to bring only three materials with him: a bucket of white paint, skeins of silk and some canvas.

“What can you do with that?” he wondered. He began ripping pieces of silk, dredging them in paint, affixing them to canvas, “and you know, it just happened.”

Quickly, he decided he was on to something: “The material was speaking for itself.” Bits of transparent silk dripped off his canvases, letting light shine through. “I decided I didn’t want the frame anymore. I decided: let’s sculpt it.”

To get there, though, he knew he’d have to manipulate his silk in new ways. “Silk has such a value in the Vietnamese culture,” he says. “For me, to destroy a piece of silk, to cut it into pieces… that’s a big deal. But I pushed myself to do that.”

He hasn’t stopped. “The work is evolving in such an amazing way,” he said in late December. “I’ve just been in the studio nonstop, producing work.” Nguyen says that kind of work ethic has been crucial to his success. Some of it is rooted in his early years working in fashion while in school, some of it is hard-wired and a lot of it is simply his love of the work.

“The more that I work with the materials, the more I realize how it works and the more capacity I have,” he says.

He’s experimenting with large-scale work, which can be challenging to mold in lasting sculptural forms, but not impossible. His largest works are now as many as 40 feet long, and he makes them in five or six different segments, which he then sews together. “It’s not evolving in a straight line,” he says.

“There are a lot of tests, and a lot of failures. Little accidents happen, unexpected things happen, and I pick up on that.”

When Nguyen’s not working on commission for collectors with requests for particular dimensions or colors, he often goes right back to where he started, letting colors and shapes come to him intuitively, sometimes reworking old pieces that didn’t originally come together, pulling out paints he hasn’t used in a while, relying on instinct.

His materials never stop inspiring his creativity. “It amazes me,” Nguyen says, “that the material, this silk, can hold a sculptural form.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.