This longtime Raleigh resident — a skilled player and lawyer by trade — helped form the Raleigh Racquet Club and influenced pro tennis at the international level.

by A.J. Carr

Throughout the wide world of tennis, Marshall Happer’s footprint is indelibly etched in multiple places. A standout player on high school and college teams, this longtime Raleigh resident found a way to turn his talent into both a hobby and career — and, at 83 and despite a torn rotator cuff, is still enjoying playing tennis, now in the North Venice, Florida, sunshine.

“We played everything and I lived across the street from a public park that included tennis,” says Happer, who picked up a racquet at an early age.

With extraordinary versatility and verve, Happer left his mark as a player, promoter and tournament director. He was also a founder of Raleigh Racquet Club, an executive with the United States Tennis Association (USTA) and administrator of the Men’s Tennis Council.

In 2021, Happer wrote perhaps the biggest book in the sport’s history: Pioneers of the Game: the Evolution of Men’s Professional Tennis. It was 1,800 pages thick until he edited it down to 871.

“I was the only person who had this history,” Happer says, explaining why he embraced the project. The intensity of his research could be likened to that of a scientist. He read the New York Times every day for years to find tennis information. He read the London Times. He collected minutes from meetings and files from the Men’s Tennis Council.

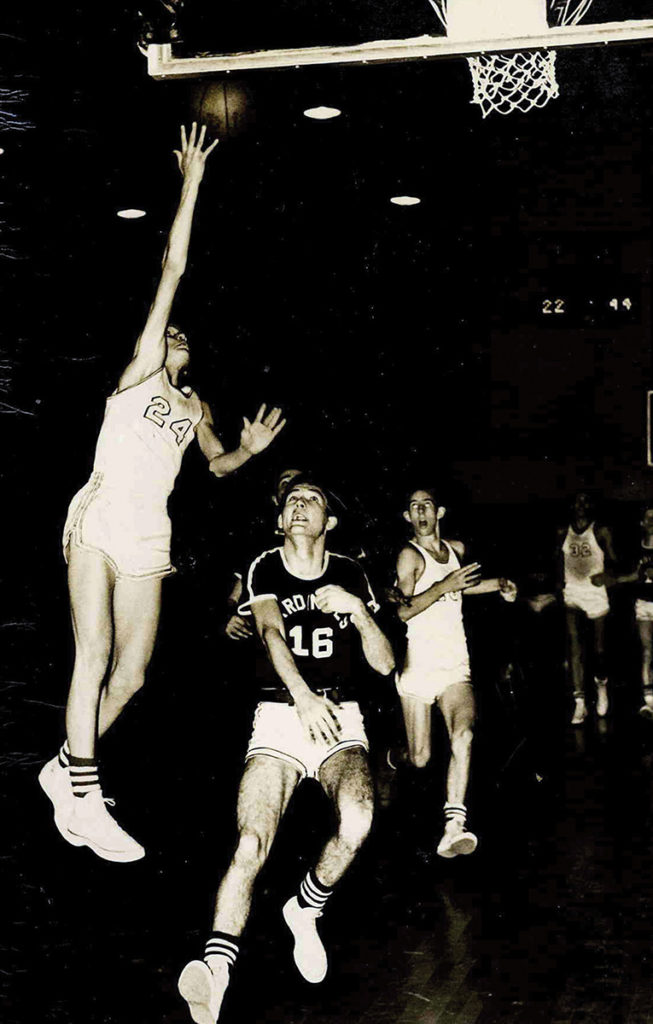

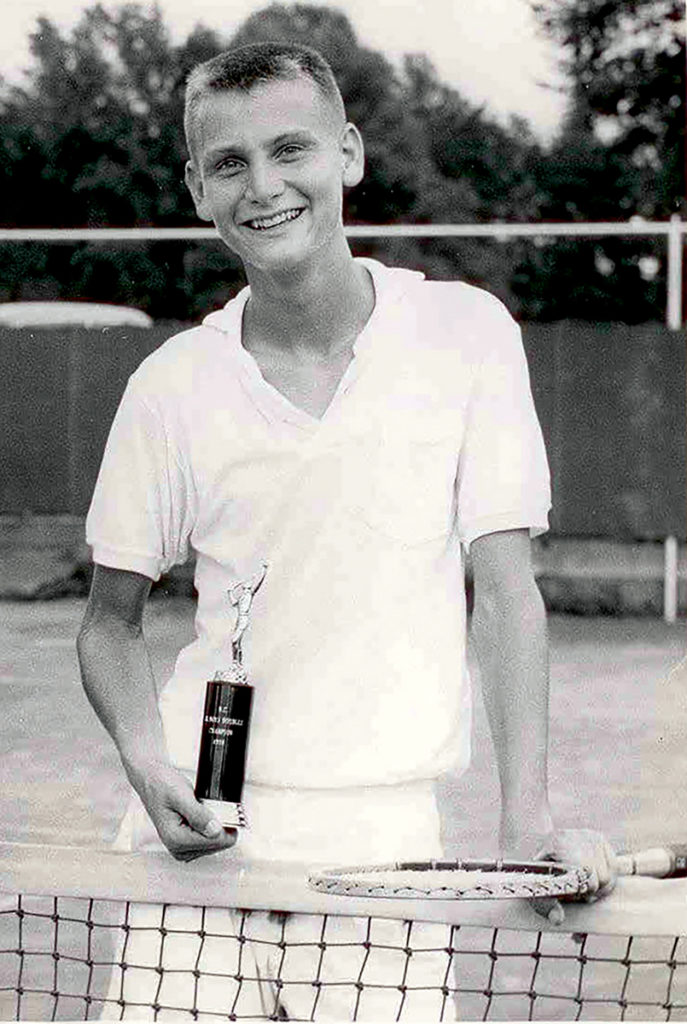

But before all this, Happer was a big achiever in his hometown of Kinston: an Eagle Scout at age 12, honor student and two-sport star in tennis and basketball. Without any professional instruction, Happer developed a solid all-court game fueled with competitive fervor. He played on the men’s town team as a 12-year-old, won two state high school titles and ranked No. 1 in North Carolina Junior singles and doubles two years. Equally effective as a point guard and co-captain, he also helped lead Kinston High to two state AA basketball championships.

His athletic journey continued at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he played on ACC championship tennis teams and earned undergraduate and law degrees. In 1964, he joined the Raleigh law firm of Manning, Fulton and Skinner and became an attorney — but remained a relentless tennis pioneer.

Over the next 17 years, Happer ran adult and junior tournaments as a volunteer and spearheaded development of the Raleigh Racquet Club.

“When I moved to Raleigh, the Raleigh Tennis Association kept up the six courts at N.C. State,’’ Happer says. “We had the ECTA tournament there, but when State said the public could no longer use those courts, we were stuck. It forced us to do the Raleigh Racquet Club.”

Happer needed to round up 125 members to qualify for a bank loan and buy land for the club. Unabashedly, he hit the recruiting trail like a basketball coach pursuing five-star prospects.

“We got all the tennis players in Raleigh,’’ Happer says, noting that Jerry Robinson, Dr. Sidney Martin, Jim Don- nan, J.W. Isenhour, Norman Chambers, Sanji Arisawa, Cy King Sr. and Bill Tucker were among the first members.

The Raleigh Racquet Club, located on Falls of the Neuse Road, opened in 1968 with six courts. Tennis interest was on the rise and RRC eventually expanded to 25 courts with a swimming pool, clubhouse, 2,500-seat stadium and 400 family memberships. Today, 54 years after its inception, RRC is alive and well.

“Marshall got things done,’’ says Cy King Jr., the Raleigh City Tennis Director from 1974 to 2004. “He was a driving force. He was a great recruiter and when he asked you to do something, you did it — and you wanted to do a good job.”

The RRC became one of the elite tennis venues in the South. With a first-class facility, Happer ran the Eastern Carolina Tennis Association Closed Tournament and North Carolina State Championship, and, for several years in the 1970s, brought in professional prize money events, the Southern Open and WRAL-American Express Championships. He served as tournament director and referee and oversaw a dedicated team of volunteers.

Players from South America, Europe and the United States came, including Jeannie Evert, Charlie Owens and a coterie of college All-Americans like Al Parker (University of Georgia) and John Sadri (North Carolina State University).

In conjunction with the Southern Championships from 1972 to 1977, Happer organized the 10-city Southern Prize Money Circuit to attract players. He also succeeded in getting a rule changed so these players could earn computer ranking points and advance to big-money tournaments.

The USA vs. Croatia Federation Cup and the popular Jimmy Connors Tour, promoted by Happer’s wife, Karen, also made stops at the RRC. The Raleigh Edge, a team on the World TeamTennis circuit owned by local businessman Duane Long and former touring pro Tim Wilkison, played there several seasons.

“Marshall made Raleigh a place on the map,’’ says Billy Trott, a local attorney and former UNC tennis standout. “He captured the tennis craze and brought in great players. He was a strong leader, forceable promoter, smart as a whip.”

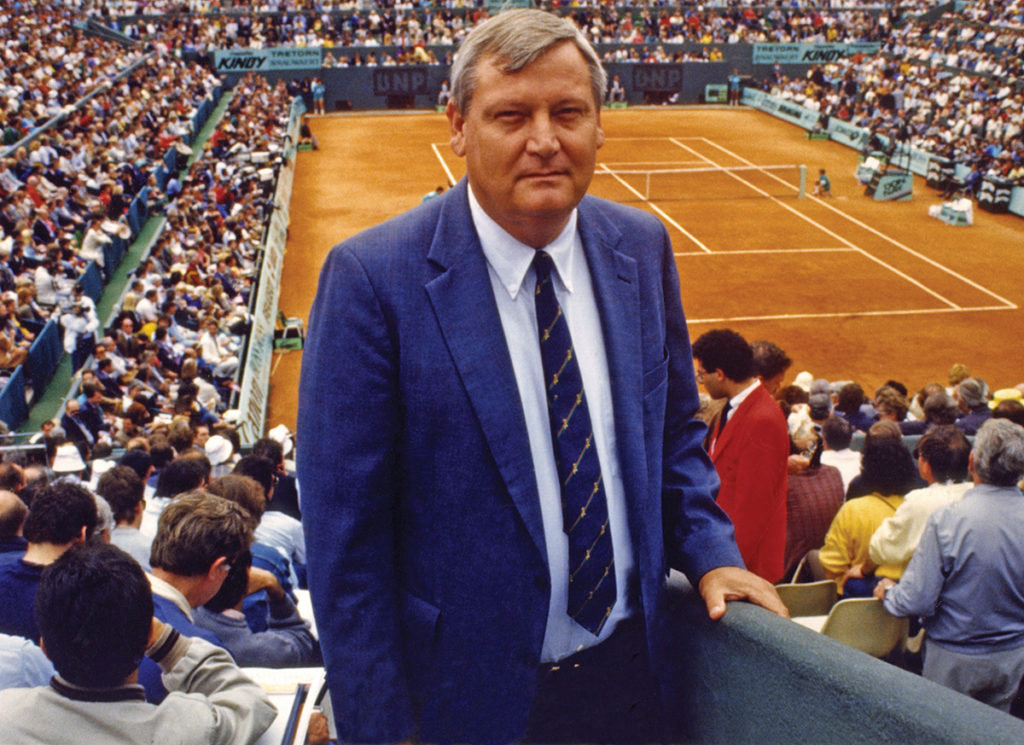

Happer’s accomplishments propelled him toward international prominence. In 1981, after a worldwide search for a tennis commissioner, the 42-year-old attorney was unanimously elected administrator of the Men’s Tennis Council by a nine-member council that included representatives from the International Tennis Federation, pro players and tournament officials.

Leaving Raleigh wasn’t easy. It meant taking a leave of absence from a successful law practice. After accepting the administrator’s job, Happer left for New York City with “a briefcase, no place to live, no office, no bank account” — facing a colossal challenge to develop the first administration for men’s professional tennis, which up until then had few regulations and little enforcement power. Excessive player misconduct, officiating problems and conflicts of interests among the sport’s different factions needed fixing.

Happer charged in — and took charge. Where there was conflict, he created calm. Where there was chaos, he brought order. Developing a strict code of conduct with a penalty system that cost players match points for misbehavior was a big move. He enforced the rules, levied fines and collected the money.

“There was $600,000 in unpaid fines,’’ Happer says. “Players would appeal, but there was nobody to listen to the appeals. I changed that in 10 minutes. That made justice swift. All nine members on the Tennis Council were volunteers. They were not prepared for pro sports.”

As a lawyer, Happer believed you had to abide by the laws or pay, regardless of rank or reputation. He upgraded officiating with the first international certification program for tennis officials and by hiring the first full-time chair umpires.

In 1983, New York Times columnist Dave Anderson wrote that Happer was “the most important man in tennis”— this, in an era that featured legendary players like John McEnroe, Jimmy Connors, Bjorn Borg and Ivan Lendl.

As a result of Happer’s leadership, sportsmanship and officiating improved significantly. His rules created strong backlash, but overall he drew praise for managing with character, integrity, fairness — and toughness when required.

“I was opposed to many of the rules Marshall held us to and we fought all the time, but looking back, he had an impossible job, which he tried to manage in the fairest way possible,” Lendl wrote in Pioneers of the Game.

“I wasn’t in the buddy business with players… I was like the highway patrolman,’’ says Happer. Yet he earned the respect of players, officials and high-ranking tennis leaders. McEnroe, Connors and Lendl — all of whom Happer fined and suspended at some point or another — each wrote letters praising and supporting him for induction to the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame in 2014.

“Marshall was without question one of the most, if not the most, visionary and influential leader during one of the most momentous and critical periods in tennis history after the beginning of the Open Era,” wrote Charlie Pasarell, former U.S. Davis Cup Player and Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) president.

“Men’s tennis today owes a huge thank you to Marshall Happer,” wrote former ATP executive director Butch Buchholz. “Professional tennis needed someone with Marshall’s passion for tennis and legal background to build the foundation for the sport we enjoy today.”

Happer fondly reflects on those achievements. “We made Raleigh a major tennis center,” he says. “If you want to feel good, go to the Racquet Club and watch people play.”

__

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine.